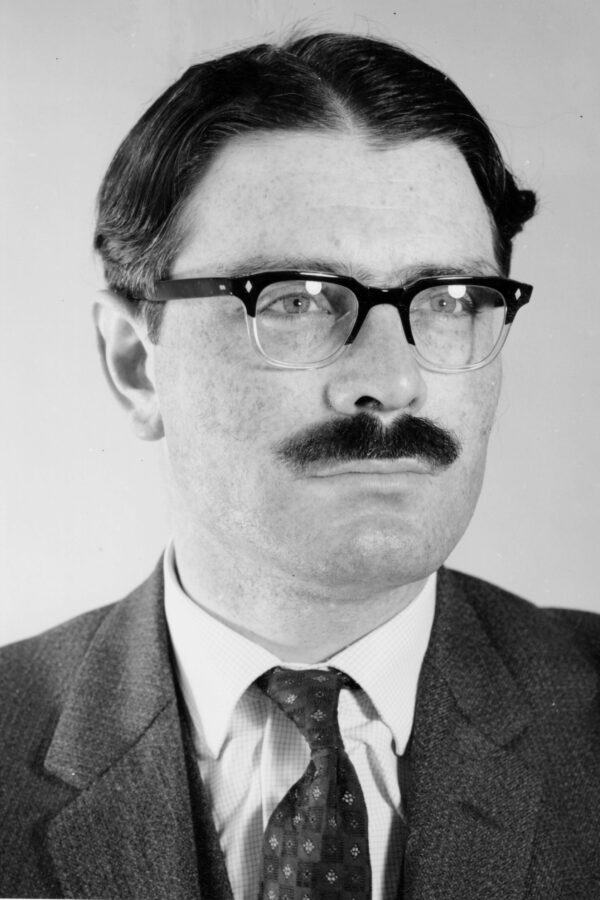

Dennis Blackwell was a key figure in the British computer industry for over 50 years, in a career that spanned and contributed to some of the most important commercial initiatives of the period. He worked for the UK flagship manufacturer, ICL, and its forbears for 25 of those, starting with English Electric in 1959 and contributed to industry institutions including the British Computer Society (now known as BCS) and the Worshipful Company of information Technologists.

Dennis was instrumental in the creation of ICL by merger of its components, being a member of the Working Party on a New Range of Computing Systems, terms of reference for which are included in his archive. He was a director of the resulting company in its formative years as Director of Systems Programming, ICL, responsible for addressing issues such as the strategy for the “next British computer” and setting up the ICL “software house” Dataskil. Dennis was also influential in other trade and standards bodies including the British Standards Institute and the British Approvals Board for Telecomms.

We are fortunate that Dennis took the trouble to record his oral history, which includes many insights to the industry and personal recollections about people and events. The abstract below is a much condensed summary of his life and career. The full transcript tells a lot more. But this is also just the tip of an iceberg of documentary history with papers that Dennis saved and collected, telling the story of the industry and a fascinating individual over more than 80 years. We will be working on analysing, reporting and displaying the story over the coming months.

Dennis Julian Blackwell born in 1929 and was the only son of James Edward Blackwell who married his mother after her husband Albert Blackwell had died, leaving a son Ted, who is 5 years older than Dennis. Dennis attended Wolverhampton Tettenhall C of E school. At the age of 10, he passed his 11+ equivalent school scholarship exam. He says: “Apparently I did rather well, because people who took scholarship exams were offered the possibility of going to various Grammar Schools, and Wolverhampton Grammar School was undoubtedly the best to go to.” He started at Wolverhampton Grammar School in September 1939 and took his school certificate at the age of 15. He adds: “I failed the first time because I failed English, but I did very well in my maths. I got a distinction and a credit in my advanced maths which was also quite unusual, and I was allowed into the 6th form to study mathematics before I had passed my School Certificate which I did in the Christmas term.” Having enjoyed his 3 years in the 6th form Dennis sat the Scholarship Exams at Oxford. With university places in high demand by returning servicemen, Dennis was advised to also apply to Birmingham University which offered him a place and he started there in 1947 studying maths. He says: “The Maths Department was quite extraordinary. It had two Professors. Professor Watson, who was a recluse, old, brilliant. Appointed at the age of 29 to the Chair and was now in his late 50s. Never spoke to any pupils. You never had any contact with him. But he lectured incredibly quickly, writing on the blackboard and following up what he had written with a duster in the other hand. “The other man was Professor Rudolf Peierls who did all the mathematical calculations for the atomic bomb. The Oppenheimer and atomic bomb work was all done by the maths and physics department at Birmingham University during the war.” Having spent his first year studying physics as his subsidiary subject which he did not enjoy, Dennis asked if he could transfer to a different subject and was offered the opportunity to join the Engineering Faculty and study Machine Drawing. He explains: “It was a very interesting period, because I learned draughtsmanship skills were really quite important. Measurements are very important, and the ability to look at an object and get the three dimensional cross sections and produce or even interpret them, was a very interesting experience. I found it very interesting, very informative, and from a practical point no use … other than satisfying the degree requirement for a subsidiary subject pass. Having done this as my subsidiary subject, I then thought that I would like to try statistics.” To study statistics, Dennis joined the Commerce Faculty where he joined a new subject called econometrics, which combined maths with statistics in financial matters. Dennis says: “It was interesting to have an insight into the combination of finance statistics and mathematics. The ability to try and forecast the likely movement of things and so forth on a mathematical basis.” Dennis completed his degree in 1950 with a 2:1 Upper Second Class Honours Degree in Pure Maths. He thought there was a strong possibility that when he was called up he could join the RAF Education Corps as an Education Officer. “I attended an RAF Selection Board in London, for people with degrees, preferably science degrees, to help in the education of National Servicemen and was offered a Commission in the RAF but one of my acquaintances at Oxford…, knew I was interested in Statistics and said “You know it’s possible you could to get into the Army unit doing statistics based somewhere down by Andover. Why don’t you not go into the RAF but go into the Army and get into this unit.” It sounded a good idea, and so I withdrew my application for the RAF and applied to join the Army, thinking that I would manage to get this unit. This was an illusion. Things don’t work like that in the Forces! Like others amongst our archives’ oral histories, Dennis’s experiences in National Service make an entertaining story in their own right and provide insights into the comedy and drama of services life in the 1950’s. Suffice it to say Dennis, managed to avoid being put on a charge once or twice for issues as varied as burning the ironing board and redirecting artillery fire, thanks to his native wit and quick thinking. He went down to Mons Barracks at Aldershot, with all the people who were not doing, not Infantry, – Engineer, Signals, Gunners, Catering Corps, greenery, and all the Cavalry, and Armoured Corps people but not Infantry, where we had I think 6 weeks of basic training on Infantry work effectively. …The cooks went to Caterham, the Signals went to Catterick, the REME went to Arborfield, but the Gunners and the cavalry stayed at Mons, for their ten weeks of Specialty Arms training. So then I was Commissioned and I got engaged at that time to a rather nice young lady called Anne Isherwood who was at Reading University and I used to visit her when I was billeted at Mons because it wasn’t too far from Aldershot to Reading except I was usually on guard duty on the Saturday nights. For some extraordinary reason I always seemed to get Saturday nights so when I was due on the Sunday I was usually far too tired to do anything other than sleep. But she graduated that year, she was a year behind me, and she invited me to her graduation ball, which I went in my new uniform as a newly commissioned Subaltern in the Artillery. I hadn’t got a dinner jacket but I had got a Number One Uniform. Rather conspicuous but rather nice! Dennis was based in Egypt for a year guarding the Suez Canal and while waiting to go and serving there relates a series of experiences that could surely only be found in 1950’s National Service Life: dealing with unexploded grenades, investigating misdoings ranging from lost army property to court martials, health hazards from salt deficiency to rabies, weapons of war and stirrup pump drill. In retrospect perhaps possibly a unique training scheme for a life in business? Dennis was promoted to Lieutenant during his national service and Captain when he joined the Royal Artillery Territorial Army R.A.T.A. Dennis enjoyed his time in the army and, having completed his two years national service, might have been tempted to make a career of it but a desire to get married and the economics of family life prompted him to join Limmer and Trinidad Asphalt based in Birmingham. The company did road surfacing company and building works. Dennis joined as Personal Assistant to Wilfred Bond the Executive Director for the Midland Region. Dennis says: “The Limmer and Trinidad Asphalt Company as an amalgamation of two-family owned firms, the Limmer asphalt company from the Limmer mines in Albania and the Trinidad lake asphalt where the naturally occurring asphalt comes from. “I joined the company and was given various jobs to find my way around and what the company did. … It was a fascinating job seeing how this chunk of a big British Company worked and, in particular, how well it handled its accounts and stock exchange, stock control, customer affairs and so forth. I learned quite a lot about the ins and outs of accounting, business and practices and contracts and standards.” After four or so years, Dennis felt it was time to move on and started applying for other positions. “[In 1958] I saw this advertisement that English Electric Research laboratories at Stafford, which wasn’t too far from Wolverhampton, were looking for people to work on the commercial application of computers in business . I thought, this is interesting, I’ve got the right qualifications and I do have quite a good grounding on what goes on in commerce these days, having looked around business. So I applied to English Electric and went to Stafford and was interviewed by Cliff Robinson and Wilf Scott who was Deputy Chair of Research at the research labs at Stafford. Which was out in the country not in Stafford, out at Blackheath Lane. And along with 2 or 3 others I was duly recruited to do work on commercial application of the DEUCE computer. Dennis explains further: “DEUCE had been developed in the early 50s, as a derivative of the ACE Pilot model developed at the National Physical Laboratory with the aid of the English Electric engineers. In parallel with that, Cambridge University was producing EDSAC (Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator) and Manchester University was producing the early Manchester machines and other bodies were dabbling in computer like things. However, DEUCE was by far the fastest machine of its day and therefore very much needed for scientific calculations and scientific work and was esteemed by universities and bodies doing scientific development, in particular English Electric in what it did for its design calculations for engines and tractions and atomic engines and the Lightning fighter which was probably a huge development based at Warton. “The idea of using DEUCE for commercial work was really quite an interesting one as people hadn’t thought of using computers for commercial work. Commercial work involved lots of paperwork, and numbers and data and so forth. It wasn’t calculation as such, it was data processing, so the idea that you could actually use a computer to help on stock control, or payroll for example, and things like that was a fairly bold one.” The concept had been proposed by Wilfred Scott, who was Deputy Director of Research at Stafford in the research labs and Dennis says that the idea developed following on the from Lyons LEO computer which had demonstrated the use of computers for commercial work. Dennis adds: “Most of the commercial applications were done on National counting machines and things like that, Bowers, NCR. and punch cards. The Hollerith Punch Card systems which went back to the American original census days and were usually mostly made for data processing and things of that nature. We had the Hollerith punch card readers and printers as the input and output device on masses of data for DEUCE.” One of Dennis’ first jobs was to write a programme in binary to evaluate and log railway wagon locations and whether they were full, empty, idle or available. He says: “I programmed this thing very carefully to process the data which they sent down via train from Liverpool to Crewe and which was picked up at Crewe at mid-morning. It would then be punched up by our punch girls on the punch cards, so it could be read to go into the computer, and we would run the programme, print out all the results which then went back at four o’clock in the afternoon on the train from Crewe. I should think this was the first daily data processing done, certainly on DEUCE, in Britain possibly.” Describing Cliff Robinson, Dennis says: “He was the head of the maths and computer section of the research labs, and responsible for the development of DEUCE with Colin Hayley, the chief engineer, from the Ace Pilot Model, built at Stafford. Cliff was a very talented mathematician and a keen Liberal. He and Allan were both members of the Liberal party and thought they could devise a method of helping in forecasting election results. They programmed DEUCE for the 1955 election, very early on, to do a forecast of the outcome of the Election. … It was the first time anyone had made an attempt to use a computer for election forecasting and they got some very accurate results which quite upset the pundits who were doing their things without any aid of a computer live in studios. This was quite a coup.” As a computer programmer, Dennis also wrote a programme to improve efficiency in steel mills, a side line of English Electric. He says: “I had the job of writing a programme for this, for several steel mills because they all had slight differences, and we demonstrated that you could actually improve the yield usually by 2% or 2.5% depending on how skilful the hot saw man was and what sort of steel they were producing.” Dennis recalls how the project also led to the idea of an online control computer. He explains: “When I was involved in the steel mill automation work at Kidsgrove in 1964/65 it was thought that English Electric at Kidsgrove, should not only be producing scientific machines and big data processing machines, but should also help the individual control system side by having an online control computer. “I was invited with Wally Parsons one of the engineers at Kidsgrove to participate in a small group to devise the order code for a small industrial online computer which was later developed and named KDM2. Ken Chisholm was the engineer in charge of the developments. It was a 16-bit word machine and was quite a small machine with an order code which Wally and I put together. A fairly small high-speed store but quite a powerful little machine and was used really for online applications in Electricity Board.” Dennis also recalls the impact of the speed of development of computers when it came to service contracts, he explains: “There was a great deal of consternation for our promotional people when a contract for the Central Generating Board had standard terms of reference that stated we should be able to maintain the equipment for up to fifty years. The idea that computers would still be the same computers in fifty years’ time, or that you would even be able to get components that had relevance was so absurd because computers were changing every five minutes. Valves had gone to transistors; transistors had gone to integrated circuits. Everything was going fast.” Dennis took on further responsibility when he became a manager and was tasked with recruiting and managing staff to be systems analysts. They supported clients on site during and after installation with training for the clients employees. He says: “I also had responsibility for the software development as well as the non-scientific machines at Kidsgrove and some responsibility under Allan Gilmour, for the Bureau work that they did at there as well.” Increasingly as we got more machines, and big customers, and they were big customers, Midland Bank was one, Commercial Union was another, Bank of London South America, who had machines, in London, two in South America. They all required quite a lot of staff, and recruiting, hiring, training and despatching these people and with all the things they needed for a one or two or three year stint to help the customer get through the planning, and installing the computer was quite a big job, and a number of these staff moved around quite a bit from one place to another. And then we had people in London of course. There was a small DEUCE bureau in Kingsway in London which was the focus for doing work in London, under George Davis who was a mathematician and computer man from NPL. And gradually as we got more people there. Then, we eventually merged with the Lyons Computer Company, which produced LEO 1, LEO 2 and later on LEO 3. Excellent machines and I had the responsibilities for all the support staff there on these. All these machines. Then English Electric acquired Elliot Automation’s computer interest (about 1967, I suppose ). Liam Bagrid the chairman of the Elliot Automation had a huge number of small companies under his wing, that specialised in individual areas of automation, many of them computer based. In fact his method of promoting seems to have been to have taken his research people who had a bright idea and say well go and run with it and if you can run a business, we’ll set up a little business and you can become the Managing Director of a small business. It’s quite an interesting way of testing the market and letting entrepreneurs make their mark. And you know, medical automation, industrial automation, anything. An incredible amount of work with small companies doing err… online controls, traffic lights, anything, washing machines. A very exciting time. English Electric also acquired Marconi. Dennis says: “Marconi became the jewel in the English Electric crown. English Electric was a huge Company with over 300,000 employees. The computer part was only about 1500, so we were only very small. But the group had tremendous tentacles and tremendous size. “Marconi was a very successful company, economically, technologically, leading in electronics, and made lots and lots of money because a lot of the work it did was for defence. The Chairman of Marconi was Sir Gordon Radley who had been the Chief Engineer at the Post Office at the time when the Post Office was the prime mover in the development of Colossus at Bletchley Park, during the war. Radley was the man who backed Tommy Flowers the engineer who developed Colossus, and provided all the valves from the Post Office to build it because valves were in short supply. He played a very significant role in the work of establishing the solution to the Enigma, and he was Chairman of Marconi and on English Electric’s main board.” During the first world war, the American Government took exception, quite reasonably, to the control of the Marconi Company in America, being a British Company, when it was doing so much of great importance to the American Government and Government interests and so they decided they would nationalize the Marconi Company in America and turned it into The Radio Corporation of America (RCA). But Marconi in Britain negotiated a very satisfactory patent exchange agreement with the new Radio Corporation of America, whereby there would be free exchange of patents between the two bodies. Marconi Britain, of course, being much the bigger body at that time. And that worked very successfully facilitating technology exchange from both halves of the Atlantic. In the mid-sixties, English Electric were interested in producing a version of the RCA 501 with British components and a team were sent out to RCA. Dennis says: “English Electric had produced these very fast scientific machines at Kidsgrove, but had very little experience of producing data processing machines, they looked to America where RCA had produced a huge bite, character driven alpha numeric machine called RCA 501, which could have up to 64 tape stations on it and could handle huge amounts of data, and printers, etc, and English Electric said, well we could produce that here under the patent agreement with Marconi.” The licensed machine became the KDP10, Kidsgrove Data Processor 10. There was great national interest in what should be the next British computer. Ferranti had produced the 1900 range, a very good machine. And they joined with BTM to form ICT, and so the Ferranti machine the 1900 range was quite a contender for having a successor which would become the British Machine. On the other hand, English Electric had its KDF10, KDF9, KDM2, the LEO 1, LEO 2, and LEO 3. So, a whole gamut of potential good machines, some of them very big machines, which the British Government wanted to back just one. And it really got hold of English Electric and said, ” You really ought to come to agreement with what we can do.” So each company put up three people on a working party which met at the Cavendish Hotel in London, to look at the possibilities of producing a successor, British Machine, which the government would put some money behind. (Editor’s note The calling notice for the Working Group on a New Range of Computing Systems, which is amongst Dennis’s archive papers refers to the “Ministry of Technology pressing ICT and English Electric to cooperate in the development of a family of computers which would be fully competitive with anything IBM has to offer in in about five years’ time”) “ … Colin Hayley, John Pinkerton and I were English Electric representatives, John Pinkerton being the designer of the LEO range, Colin Hayley being English Electric’s Chief Engineer Computing. We met and really sensed that it is possible, we could develop a machine which would not be either a derivative of the 1900 range or the English Electric System 4 range, but could be a new machine. But it could be done. But we could only do this if there was an agreement commercially between the parties. ICT was an independent quoted public company, English Electric Computing was a mere little entity of the English Electric Group, and whenever you have a joining of some sort there is commercial interests involved. Also Ferranti and Armstrong, Vickers Armstrong, still had some slight interest in this because they had a shareholding from their earliest things. So there were a lot of people who had to consider their shareholders, as well as the technicalities of technology of doing things. The net result was that the Government was told more or less, “You can’t do anything unless we have a single commercial entity. Hence ICL was formed. And I think English Electric expected to have the dominant share in this. At the time that English Electric took over ICT, ICT had already been commissioned by the UK government to be involved in the development of the Computer Design Centre which would be based in Cambridge. Professor Gill at London University suggested that what the government ought to have was a Computer Design Centre and wouldn’t an Atlas be an excellent machine to base it on. And that idea received a lot of blessing, partly because Ferranti wanted to sell the machine, and it was a very powerful machine, and it would go to Cambridge because Cambridge was a good place to do that sort of engineering work. Arthur Llewellyn was the Director of the Computer Aid Design Centre at Cambridge. Dennis and his team worked with him. Dennis adds: “It worked very well and went from strength to strength and eventually the contract was assigned to the ICL software house, Dataskil, which I was responsible for setting up, and of which I became Deputy Chairman, with Alan Roussell as Managing Director, and Peter Hall as the Chairman. “The reason we set up Dataskil was that we had staff from all over the place doing software work and applications programme work for not only new machines but legacy machines; machines that had been developed and were being used by people in the field, some of them being quite old. We had every British made machine in existence except Stanteg Zebra. There were oodles and oodles of them! And some of them were quite old, but people were still using the software and the software needed to be maintained and in some cases developed.” Dataskil had about 600 to 700 people in it initially and Dennis adds: “it simplified the structure in ICL no end.” Following the successful launch of the KDP10, in the seventies, as part of ICL, Dennis was sent over to the US to help in the development of the software of the successor machine. He explains: “IBM had come out with a range called the 360 range and RCA were producing their own equivalent of this, which was supposed to be programming compatible with IBM. We sent a team over to work at Cherry Hill, Philadelphia to help the software development and also to ensure that when we got the right to build that machine we would have the inside knowledge of how the software worked. I went over as part of the business of supervising the relations for joint meetings with RCA management to see how they were getting on. Usually they were miles behind what they had promised.” I used to go from Manchester to up to Prestwick and we flew on the Great Circle route over the back end of Iceland, and Greenland and down that way into, we err…, Philadelphia. Quite an interesting journey. We always came back on a night flight which left about 10 o’clock and they gave you supper, and by the time you had just got to sleep they’d be waking you up ‘cos you’d be arriving in England. And at Prestwick they’d put on music to…. Whilst some of the people got out to go to Scotland. And they put on strident bag pipe music!!! Which at that time in the morning was not the sort of thing you wanted to listen to, when you had only had two hours sleep and you were dog tired. …, ICL had quite a connection with the computer market in Australia. It was quite small of course because Australia was only populated by 28 million and the population was spread into about four or five big cities and they were very anxious to catch up with the modern world, scientific work and so forth. But they hadn’t any computer industry of course. So they either looked to America or they looked to Europe. And being British they looked to England first. And English Electric sold fast machines to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, CSiro or something like that, in Australia. ICT had had quite a lot of punch card business there and so they built on that. And it was thought that if it was possible to, umm…, to encourage the latent talent in Australia, in the universities there, and there were some very able people, instead of going to the States to learn things or coming to Britain, they could develop things themselves. And that’s why I went to Adelaide and came back having done that and set up that….It would be early ’70s . Quite early on. Unfortunately when they, ICL had a change of top management, and American Management came in, they scrubbed the thing, they liquidated it, thought it was irrelevant, which was a great mistake. In much the same way as they got rid of the software unit in Dalkeith Palace, Scotland, which we set up … In the seventies, Dennis was also involved in establishing a computer centre for ICL at Dalkeith Palace in Scotland, at the time, the Wilson Government were encouraging companies to move out of London and initially suggested Middlesbrough as an option. Dennis wanted to have somewhere closer to universities and Scotland became an option. He says: “At the time of the merger we had 17 different locations of software people under my wing. It was a difficult job in trying to rationalise these into some sensible organisation shape, let alone unison. I suggested to Peter Hall, the Director of ICL for the software, that if you want to go north, Scotland is the place to go. It had oodles of Universities there desperate to be involved in high tech and so forth, and we already have some people there.” Dalkeith Palace, one of the Palaces belonging to the Duke of Buccleuch, was eventually found as the location. Dennis says: “It was an ideal campus and space for oodles of people. The only difficulties were that you couldn’t put a computer inside this building because it was a listed building. So we suggested we could build a separate little computer establishment in the driveway under the trees and they thought that could be done. ICL spent £100,000 on doing the place up because it hadn’t been touched since about the First World War.” In the early eighties, ICL suffered financial difficulties, Dennis says: “When ICL was in its difficulties they brought in Tom Hudson, who had been Managing Director of IBM UK, and retired as Chairman of ICI, with Arthur Humphreys, who had been ICL’s Managing Director, as Deputy Chairman. Geoffrey Cross was from Univac, he came in as Managing Director from America, and there was this little separation of powers between the Chairman, the Deputy Chairman, and the Managing Director, which was very visible. “At that stage, I was acting as manager of Strategic Planning, as well as in the Corporate part of ICL as well as General manager of Multi National Data, the Belgian Study company. “I was effectively sidelined, I think they wanted to get rid of me but I had children at school and university and so forth and I just sat tight and so they offered me the post of being manager of Multi National Data, which was a joint study company with Control Data America. It was a Belgian company, incorporated Belgium. I was Director and Secretary of this along with Control Data, National Cash Register, and a CII which was the French computer company sponsored by De Gaul and Honeywell. “The idea being that these other companies would collaborate in developing common designs of peripheral devices to attach to their mainframes, so that you had the ability to purchase from a larger market and avoid any incompatibilities. The idea was sound but it didn’t actually work, because in the main, the American market was vastly larger in terms of its requirements for peripheral devices, and tended to dominate where people got printers and tape stations, and drives of various sorts, and it didn’t really achieve its objective.” Dennis noticed a distinct difference in ethos between American and British attitudes in the business. He says: “Geoffrey Cross had the reputation of firing anyone over the age of 35 at management level as part of the principle of introducing new blood. Whether he did that actually, I don’t know, but certainly he was a young man and he believed that people should be young, and that experience that people who are over that age, and I was over that age at that stage, let alone more senior people, were obviously not able to accommodate the fast moving technologies that were coming on in the computer world generally. “That attitude very quickly met difficulties when he was dealing with English clients, because they were much more used to dealing with older representatives of big companies. So, he tempered things down quite a bit. I know when he first came, he was an open necked shirt and casual style, which doesn’t go down well when you are meeting Ministers of the Crown on big contracts. He then changed and started wearing suits and ties. Just little things like this. “I think there was a certain amount of arrogance on behalf of the Americans – they knew more about computers than the British did, which wasn’t actually true, because the real development of computers started this side of the Atlantic.” When ICL decided to supply equipment to the military, it had to undergo a process of having to be certified to the defence standard 05-21. As Director of Quality Assurance, Dennis oversaw this undertaking, he says: “You had to comply with this standard and it not only covered the things, but the whole manufacturing and development process. This meant that because ICL was an integrated company, one manufacturing, one development, one sales organisation, with one or two minor subsidiaries; bureaux companies selling computer bureau time, and a software house Dataskil, ALL of these bodies had to go through a MOD evaluation, against the MOD standard 05-21. “It was a major exercise which required practice runs on every establishment, manufacturing and developing, throughout the entire company. A really very significant task which was overseen by me as director of Quality Assurance, using guile, pressure, peer pressure all sorts of things to achieve the desired result.” Dennis remained at ICL until he took early retirement in 1984. He was one of very few who remained with the company from its early inception as English Electric through the many mergers and acquisitions to create ICL. Following the publication of the Younger report on Data Privacy in 1982, the Government decided to take action and invited consultations with interested bodies, this included ICL, and Dennis took responsibility for producing the paper from ICL. He was also involved in submissions made by the British Equipment Trade Association, BETA, and was nominated to join the working party on the National Electronics Council to prepare their submission. As a result of his help, Dennis was invited to become an associate member of the National Electronics Council. Dennis, as a member of the British Equipment Trade Association (BETA), was also involved with a government project to establish standards and an approval process for equipment to be attached to the telecoms network. Then, if you wanted to attach a device to a Post Office line to make, it talk to a computer, you had to rely on the post Office to provide the modem. (And the Post Office, having developed its networks over many years, had not got very standard connections which made life very difficult for all manufacturers of peripheral equipment.) He says: “Kenneth Baker, the then Minister of Technology, introduced the idea of the British Approvals Board for Telecommunications which should be the statutory regulatory body for approving things that you can hang onto a telephone network. (Editors note: this at a time when equipment to be connected to the network had to come from one of only four manufacturers, despite widespread use of unapproved equipment- see e.g. Wikipedia)The Business Equipment Association, which I happened to be on the Council, and Treasurer at the time, was invited to participate in this in two ways. First of all to make sure that the industry put in their best people to work on it at working level, and that since the Government hadn’t put any money into this, to provide some money to get the thing going. “It was set up under Dr. Vivers who was the Director General of the Business Equipment, Electrical Equipment Approvals Board, which was the thing that approved washing machines, electrical irons, etc, and therefore he had a lot of experience in regulating control of things that were electrical. He became Director of the British Approvals Board for Telecommunications, and I represented the Computer and Business Equipment Industry as a Director of that body. I became a Director of BABT.” At the same time, Dennis was also Treasurer and Council member of the Business Equipment Association, Associate member of the National Electronics Council, a council member of the British Computer Society. He also set up in the Equipment Society an exhibitions company to run exhibitions for business equipment. He adds: “So I had a finger in the professional, the business, the technical, the statutory, and the research industries.” Dennis was a member of BCS from its early days having been encouraged to join it when he worked at Nelson Labs. He was invited as a member of BCS to join the Council by Peter Hall his ex-boss and the then President of BCS. Having been elected to Council in 1970, Dennis then became involved in the discussion about the organisation changing status from a ‘club’ as he describes it, into a professional body. He explains: “It became very clear as time went by that there was a need for the quality of people doing computing work to be in some sense registered. The Society therefore had a dilemma between those who wanted to keep it going as a sort of club and those who saw it as being the embryo of a professional body with professional standards which it requires members to meet. “Peter Hall asked me to look at this question of the issues over whether the future lay in being a bigger and bigger club or a professional body. In parallel, the Engineering Bodies had been grouped together under the aegis of a body called the Engineering Council which was empowered by statute to award the grade of Chartered Engineer. “There was a general interest in people seeing that the work of being a systems engineer in the computer sense should be regarded with equal seniority and respect, and the BCS should aim to become a body under the Engineering Council with its power to award a Chartered status to professional members. “I produced a report that said the way forward is that we should be a professional body and that we should seek a proper recognition as a professional body. This was duly put to the Privy Council who were the bodies which had statutory power to grant status for bodies. It went through with the blessing of the Privy Council, which gave the entre’ for BCS to deal more formally with the Engineering Council about becoming a recognised Engineering Body under the Engineering Council. This meant in turn also that procedures for entry, examinations for professional skills and for disciplinary matters for dealing with people who failed to meet them or were subject to complaints had to be there in position and in working order. This all took some time.” Dennis was then asked to look at the procedures and found them lacking, having made significant proposals on how they should be strengthened, the new procedures were accepted. He went on to chair the BCS Professional Advisory Committee. At the same time as being involved with BCS, Dennis was also invited to join the British Standards Institute (BSI). He says: “I had been invited by one of my old colleagues from ICL, who had joined the BSI, to Chair the Quality Assurance IT Committee, which BSl’s Quality Assurance Board had set up to look at Quality Assurance of IT matters. As a result of being Chairman of their committee I became a member of BSl’s Quality Assurance Board under David Penny, the ex-Director of the National Engineering Laboratory at Kilbride.” While acting as the BSI Quality Assurance Chairman of the committee on IT, Dennis met Andy Anderson who worked for Shell Oil and was a liveryman of the City of London, and a Freeman of the City of London by paternity. Andy suggested to Dennis that with the growth in the number of IT professionals in the City, there ought to be a Worshipful Company for them. He volunteered to nominate Dennis to become a Freeman. Dennis, having known a number of liverymen and Freemen whilst growing up, says: “I liked the idea … and was quite pleased with the idea of being involved. The result of that, I was duly nominated to become a Freeman of the City of London and granted the Freedom. 1986.” His becoming a Freeman coincided with a proposal by BCS and the Computer Service Association to the City with a view to forming a Worshipful Company. The Company was established in 1985 and Dennis was elected as a Liveryman, a founder member of Information Technologist’s Livery Company along with about 25 other people. He says: “I now, and have, for some time, participated in a number of Livery activities, most particularly the duty to elect the Sheriffs and the Lord Mayor at the Guild Hall each year. “The Livery Company has made great progress in offering its abilities to other bodies of the City who are not so competent in IT matters, to help them on their way. More recently, it sponsored an Academy in Hammersmith, for which £1million was collected from members of the Livery. In accordance with a lot of City traditions money is found for charitable affairs. Vast amounts are available, and a lot of work is done of a charitable nature. More particularly the Livery Company has done a lot of helping Charities in the Greater London area to work with the difficulties they have in using computers. As such, it has achieved quite a recognised standard as the 100th Company, Livery Company in London. A number of its members have now been Lord Mayor. They were Lord Mayor not because they were our members, but members of other Livery Companies and very senior people in London but have also become members of our Company.”