Past masters of the Worshipful Company of Information Technologists and Presidents of the BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT as well computer scientists, writers and academics attended AIT’s 2025 Forum, which took place on 28 January at the Worshipful Company of Information Technologists’ Livery Hall and online.

Four sessions exploring Norms for the Digital Age

The forum consisted of four sessions led by a multi-disciplinary set of academics, practitioners and leaders from IT, civil society and business. Sociologist, Professor Rich Ling, opened the Forum up with a talk on the evolution of digital norms and this was followed by a roundtable discussion arguing for a more professional IT sector, which was chaired by Professor Jim Norton OBE and featured Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE, Lord Lieutenant of London; Paul Martynenko MBE, a past master of the BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT and current BCS President, Alastair Revell.

Journalist Bill Thompson then explained how digital technology has destroyed the economic model of the industry and teacher Ravi Chagger and coach Kieran Gilmurray talked about the challenges and opportunities digital technology provides for education. The forum also included three acedemic papers from Dr Kate Bradley on Telephone Helplines, Patricia Esteve-González on Cybersecurity Capacities for the Application of UN Cyber Norms and Towards Assuring Data Fairness in Trustworthy Machine Learning by Dr George Zoukas and Dr Jonathan Foster.

Building on AIT’s extensive oral and visual record

In his introduction AIT’s chair of trustees, John Carrington, told the audience how the event builds on the charity’s extensive oral and visual record of people involved in IT since the 1950s. “AIT is about people, hence the topic today Norms for the Digital age, is about how people behave. The dictionary definition says, our shared beliefs or values and the human behaviour that support these within a given society and the Forum’s discussions are an open addition to our virtual archive, accessible to all without charge.”

With the progress and adoption of new technologies our contexts of use have shaped the norms governing these different information and communication technologies, such as the internet, social media and the smartphone. Now with the addition of generative AI chatbots such as ChatGPT, experts at the Forum discussed how together they are affecting professionalism, journalism, education and international cyber security.

Professor Bill Dutton, AIT Trustee and chair of the Forum Programme Committee, who is an Oxford Martin fellow in the Global Cyber Security Capacity Centre at Oxford University, and a senior fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute, said: “I think norms are shaping, as the title of Professor Rich Ling’s opening keynote speech indicates ‘everything everywhere and all at once’. Norms are really critical, they make a difference and if we violate norms, that makes a difference, it really matters to people.

“When norms are broken or when somebody violates a norm, that’s what really focuses our attention on norms. The panel on professionalism illustrated that it is a norm in itself, and when that’s violated, it really damages society and this was highlighted by the panel with the Horizon scandal and the importance of trust and their drive to create professional qualifications across IT.

“And that professionalism is really something that resonates throughout all the areas we covered including IT, journalism and schools. And that computers, the internet and machine learning are all challenging IT, professionalism and schools in terms of what we do.”

Click on the accordions below to read the highlights of the talks and view a gallery at the end.

Professor Ling’s background is as a sociologist working in technological environments in Norway, for telecommunications company Telenor and its predecessor Televerket, and in the research department at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Normative consequences of digitalisation

Prof Ling, who also edits the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, focused on the normative consequences of digitalisation and began with two anecdotes from his career where digitisation challenged norms, with the first unsuccessful and the second a phenomenal success.

In the early 1990s while working with Televerket on its ADSL (asymmetric digital subscriber lines), which involved sending digital signals through copper wire and promoting services such as video on demand, Prof Ling, was tasked with finding the content and the guinea pigs to try it out.

He said the content was challenging because of ownership issues but finding the guinea pigs was also had its challenges because the servers were in the centre of Oslo with ADSL having a reach of a kilometre or two.

“I eventually had a list of 40 or 50 people that I could call that fulfilled the technical requirements. I remember the first three or four calls that I made. Somehow I got into an apartment building full of old women. Now I can speak Norwegian fairly well but they quickly understood I was American. So, I was a foreign guy trying to explain to elderly women that I want to give them a box that will give them video on demand through their television set and it just didn’t work.

“They didn’t want this guy who spoke funny Norwegian messing up the antennas or the cables and messing around with their TV. It transpired that the precarity of the technical setup resulted in a norm. They had the norm of watching television and the norm of not touching that set up. And I wanted mess around with that norm.”

So the elderly women of Oslo were a barrier too far for technology breaking norms, however, another project that Prof Ling was involved with at the same time had a more successful beginning and changed people’s lives and behaviours.

He was working with mobile communications, which was starting to take off in the early to mid 1990s, with digitalisation and 2G as well as demand for Nokia growing exponentially with favourable subscriptions packages constantly changing.

“And we were just seeing a flood of mobile phones into society and teens had the prepaid subscription, so the parents weren’t worried about the teens running up crazy bills,” he said.

“That’s red meat for a sociologist, because it means things are changing and what was changing was the micro-coordination. This was a term that I wrote about very early on where people use their mobile phones to coordinate their daily activities to and plan with others, where they can rearrange at the last minute. That has really changed the way that we interact and the way that we work out our adjustments and our appointments. It’s changed the norm of how we coordinate society.”

Norms, folkways, mores and taboos: an archaeology of neologisms or memes

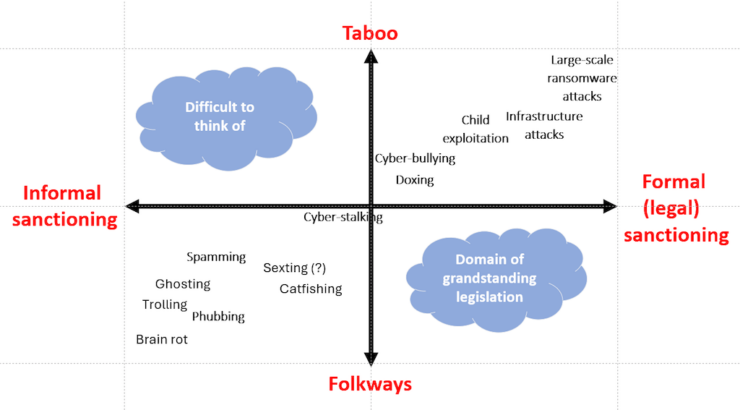

Prof Ling used neologisms or memes as a lens to understand normative behaviour. He said they encapsulate a sense of change, they give us these neologisms, they give us a shared touchstone, and we can use them to understand social change.

He also referred to William Graham Sumner the sociologist and priest at Yale University [in the late 1860s] who wrote a book called Folkways and came up with a hierarchy.

“According to Sumner, there’s a taxonomy of different types of norms. Folkways is the most basic. It’s just shaking hands, it’s, making small talk around coffee. You know, those kinds of things that are on a smaller level. Mores, what is moral, are at a higher level and then at the top is taboo, which is sacred or sacrosanct. If somebody violates a taboo, its results in a visceral feeling, it’s repugnant to society.

“Norms are standards of behaviour. They’re often invisible until they’re violated. And you see this during the swearing in ceremony for senators this month and Bruce Fischer, Republican Senator Deb Fischer’s husband, refused to shake Kamala Harris’s hand. That was a violation of norms.”

And then there are levels of sanctions, such as informal sanctions where norms are often encoded in terms of etiquette, and people will say you should do this or that and books are written about it.

There’s also formal sanctions, for example, explicit rules with explicit punishments, and when you get to that, it’s quite often in terms of law. There are legal decisions being made. According to Emil Durkheim, a sociologist, there’s civil law and criminal law. Civil law is like contractual stuff. I agree that I pay you this. I didn’t do it. We can go and discuss that. Criminal law is things that go beyond that. For example, if I go out and hit somebody unprovoked, they can take a civil case against me, but also the State says you shouldn’t be doing that, so a criminal case can be brought.

You can even go beyond that, and I think that’s one of the things that we’re starting to see with state actions against other actors where military strikes, cyber warfare and those kinds of things are another level of sanctioning.

Memes and neologisms

Then, of course, there are memes a word first coined by Richard Dawkins, in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene and neologisms is another word. It’s an idea or symbol of practice that carries social meaning. Cultural analogue to genes according to Dawkins, it can self-replicate and mutate and given their social biome.

They’re communicated from person to person also digitally. Now, when I say memes now I was talking with my daughters about this, and said, and in their mind it was internet memes. But I’m talking about something a little bit larger, for example, Me Too., The Maga movement, woke and Klemz, which means hugs in Norwegian but with a z instead of an s. When my daughters were growing up, they would sign all their text messages like this. That was a meme within their group to identify they were the type of people who would spell it like that.

So there’s this idea of a practice that carries social meaning and that we use in order to identify or to focus on different sorts of things. We’ve also had the idea of snail mail as one of these digital neologisms. They illuminate a social discontinuity, encapsulate a social awareness of a new phenomena.

Phubbing to brainrot

He then described a correlation of digitalisation from phubbing to brain rot, which was the 2024 word of the year for the Oxford dictionary, and ghosting, all of which have changed or violated norms of local interaction.

This escalates to spamming, doxing, catfishing, and then you move into the upper end where formal criminal law and legal sanctioning sits with sexting, child exploitation, infrastructure and large-scale ransomware attacks.

“I’m going to just walk through this folkways and largely informal sanctioning. Phubbing is phone snubbing. So when somebody takes out their phone while you’re talking to them and they’re looking at their phone and maybe half paying attention to you. For younger people, though, it’s fascinating because there’s sort of a nascent development of rules of etiquette, of when you can phub, and how much, in what situations, and they’re quite quick, shifting back and forth between face-to-face and mediated interaction, and they can temporarily excuse themselves. ‘Oh, wait a minute. My boyfriend’s just text to say he wants to break up. Okay, what was that you were saying’ so they’re very nimble.

So, phubbing points to an issue, but it also illuminates one of those areas of digital norms where we are having a social discussion.

Mores

“Now mores, which increasingly encompass formal criminal sanctions. And in this case I’m going to use a familiar one: phishing.

“It’s perhaps the most common online criminal behaviour. It’s unsolicited email text and phone calls. It appears to be legitimate. It requests personal information, login details, to install corrupt files and/or to steal money. It’s 5 to 10 times more common than other cyber crimes.

“And interesting, it plays into a sense of urgency to susceptible groups and according to research they are predominantly women who are more conscientious and those who have problems with cognitive load.

“Phishing is covered both by civil and criminal law and like phubbing, it’s a breach of etiquette, however, you are potentially going to jail for phishing. It is an offence covered by The Data Protection Act of 2018, the Consumer Protection Act of 1987 and Fraud Act of 2006.”

Taboos

Taboos are perhaps the most difficult. And digitalisation makes taboo activities possible, they’re criminal offenses, distribution of child porn, online suicide packs or internationally, they can be used as justifications for attacks. And they’re state sponsored cyber terrorism. Perhaps the first one was 2007. The Russian attack on Estonia, Russia basically closed down the internet in Estonia over a dispute about moving a statue. This led to the Tallin Manual, which is the set of international rules of, does a cyber-attack constitute an act of war?

And that’s you know, the big question right now in the Russian cyber-attacks on Ukraine previous to the attack on Ukraine. They there was a bunch of, and it’s happening all the time. Different actors around the world are doing that. So AI is a new domain, another one up in the upper right hand. You see that guy standing there with the earplugs? It’s a little bit difficult to see, but the thing over the left is a rifle in some kind of a machine that is run by Chat Gpt.

It’s a rifle that you know he uses chat gpt to shoot with. So again. this, it seems like we’re moving into sort of a new space new space in this context.

Ambiguous concepts

I’m going to talk a little bit about sexting, because this is really a weird one. It’s it can be criminal or not. Again, here’s how people met each other between 1950 and 2020. And you see that the blue line is. They met through friends. They met at work. They met through family or grade, school or church, or something like that. All of these things just down. The only one that goes up is online.

That’s, you know, that’s changed since around 2000. That’s just tremendous number of people who are meeting online. And all of these other ways of meeting other people. They’re falling apart. And you know you just expect this because the dating pool expands tremendously. If you’ve got a if you’ve got a sort of a broker like Tinder.

So is in that context, what role does the mobile phone and photography play? Well, sexting? It’s a, it’s mutually nature of sexting. You know where the one partner sends a photograph of themselves, naked or quasi naked to the other.

It could be a part of a good faith. Romantic bonding in the dyad. That’s a good thing to have a huge level of trust with your partner, that you’re doing something a little bit out of the norm, but it’s between us, and it makes us feel like, you know, that’s a huge level of trust. That’s a huge bonding element, so I would call that good.

But it can be used from one person to another in hopes of initiating a relationship. Hey, Buddy, you know, here’s what you know, what I’m offering. or it can be between a couple that’s gone from each other, and they start sending the photographs out to third parties. if both partners consent consent, and they’re not minors. Then sexing is not governed by any formal sanctions.

If sex they’re set to outside the relationship without permission, then it can. If the child, if one of the partners is underage. It’s child pornography.

It can involve harassment, revenge, porn, and breach of privacy. And it can be a criminal act criminal. In other words, it’s not the other person that will sue you. It’s society that will seek revenge, or, you know, seek a case against you.

Dating has changed tremendously because of digitalisation. The platform platforms like tinder, allow for a different type of dating than we’ve seen before.

And based on also a digitalisation, mobile phones and digital cameras. It allows for a different way of courting than I experienced when I was growing up.

It’s difficult to think of informal sanctioning for taboo activities we don’t do that.

We often don’t know that we need the rules until a boundary is breached. For example, the holocaust breached a boundary that resulted in the universal declaration of Human Rights.

I’m guessing with AI and the things that we’re dealing with now. There’s going to be things coming there that that we’re going to have to deal with and we’re still, I say, we’re still early in the era of digitalisation.

The transistor was developed in 1947, So we’re about 80 years into the digital era.

The printing press. It went about 70 years before Luther did his thesis in Burdenburg. So we’re still relatively early in the digital era, the social norms, the social institutions that we have a lot of inertia that are only now being slowly changed by digitalisation. It could be that a lot of the large scale institutions that we have will be mute, mutated, or changed, or new ones will arise based on digitalisation. So we’re still working that out. And I think AI is kind of a turbo element in in all of that.

Digital Grandstanding

AI based terrorism and hacking is happening. For example, we remember the fellow you see the the Cybertruck burning out in front of the Trump Hotel in Las Vegas. Apparently Chat GPT was used in order to develop parts of that in order to do that. So there’s an example of terrorism based hacking.

AI based cheating another one that I’m having a little fun with tech Bro imperialism. And also, just in general, AI generated content. About a week ago I was having a talk with a fellow a lot younger than me and he called some text that had been produced that he received chat slop.

The idea of Slop is being used to describe AI generated text passing for human generated text. It has a Wikipedia page. So let’s think about what does that do normatively. That makes all of us need to read everything as though it was a Turing test. But you know, we have to have new ways of thinking about what is it we’re reading? Would this be something that Chatgpt would produce?

What would it look like if Chatgpt produced it? You know, what are those elements? How can we tell? And so we’re sort of into a grey zone with that. Here I’m suggesting that this is one of the new memes or neologisms that we’re going to have to deal with, or that we have in our future.

Early in the IT industry, there was a high value placed on professionalism in programming and the design of IT. Has the norm of professionalism been eroded by the personal computer and more general and high-level programming languages? Have IT disasters, such as the Post Office Fujitsu Horizon Scandal, created new demands for professionalism in IT?

This Roundtable Discussion featured chair, Professor Jim Norton and distinguished speakers, Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE, IT entrepreneur and Lord Lieutenant of London and Paul Martynenko MBE, former IBM senior technical executive for Europe and a BCS Past President and current BCS President Alastair Revell.

Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE

Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE outlined the professionalism he encountered while working as a systems engineer with IBM in the early ‘70s, designing, writing, testing, implementing and maintaining the systems.

“What was important about that time in technology from the major companies, and we were the only companies selling computers, was that our customers trusted us to deliver, and their trust wasn’t misplaced, because our task was to deliver, and the consequences not delivering were unimaginable because it would have destroyed our reputation. So, the market pressures all that time ago made sure that we behave professionally.

“So you trusted IT people in the same way that today we would trust a doctor or a dentist: on reputation. And when it went wrong, which it did from time to time, there were consequences inside the business, because it was a professional responsibility.

Sir ken said he was very proud of that and how being a fellow of the British Computer Society he was a CITP [Chartered IT Professional].

“But I’m not, and I emphasise this, qualified now to design to write, test, implement and maintain systems. And sadly most of today’s IT practitioners are also not qualified. They may well have got a Microsoft certificate or the like but that’s not what we’re talking about in professionalism.”

He described the frustration he had witnessed in his own staff in his Whitehall office when dealing and trying to be understood by IT companies and said we all know about cowboy builders but in society we don’t talk about cowboy IT people.

“We had a problem with our IT system. And I watched my assistant clerk on the phone to the technologist who’s supposed to be solving the problem and she got angrier and angrier and angrier, trying to get the person to even listen, never mind understand or more importantly solve the issue and that is just not professional. But you know what, we just take it for granted that IT is like that.

“If you talk to members of boards of companies, and I give a good example of a director saying to me, ‘I didn’t really know how to talk to IT people, they talk their own language. I don’t even know how to ask sensible questions’. I said, well, you recently built a new head office, when the architect came did you question them about what they were designing? ‘Oh, yes’, said this lady, and I said. ‘Are you a qualified architect?’ and she said. ‘Of course not. I’m an accountant’. So I said, how come you feel you can challenge an architect but not an IT person? And she said, ‘because I’m afraid of IT’.

This has a massive consequence. In 2023, you will remember that amazing air traffic control collapse. It turns out that there was a system failure and the engineer who was supposed to mend it was working from home and couldn’t get his password to work. That meant he had to drive in to make the thing work and in that time 700,000 passengers were inconvenience and £100 million of cost was wasted.

“However, the most humiliating experience in our lifetime has got to be the Horizon scandal with the Post Office, where people have lost their lives as well as money, all because of very poor professionalism in technology.

“Now, with a new government, there is hope, because they have stated lots of time that economic growth is their mantra. And that economic growth will absolutely depend on information technology, it cannot happen without it. There is nothing, whether you’re thinking about agriculture or mining all the way through to something much more complex and sophisticated. It will be dependent on the application of information technology.

“That means that we need to take IT, computing systems and networking a lot more seriously than we have been.”

Paul Martynenko – The complicated system of skills and encouraging professionalism

Paul Martynenko MBE says that SFIA [The global skills and competency framework for the digital world] has defined 147 skills for the information age.

“And if you look at cyber security, there are 15 specialisms. It’s far more complicated than it ever was. And the integration of these systems means you do need a very structured, clear and responsible approach to professionalism. Trying to get people to do that is a bit of a challenge.

“Jim [Norton] and I worked on Chartered IT Professional (CITP) early on looking at a certificate of current competence. But how do you define a certificate of current competence when it’s so broad?

“What we’ve just done in BCS is to say, okay, so CITP is a standard of behaviour across IT but you can have specialisms. And we’ve defined our first specialisms as cyber and data.”

Cyber essentials promoted by the National Cyber Security Council is something many companies are now taking on board and I would argue that your Chief Information Security officer should be a chartered professional. I think everybody understands cyber security is a really significant problem. If you could find similar areas such as in AI and other specialisms then potentially we could have a few where it really does affect life and livelihoods which everybody understands.

There are two very interesting reports that came out this month [January]. One’s from the National Audit Office: Government’s approach to technology suppliers: addressing the challenges and Secretary of State for Science, Innovation & Technology, Peter Kyle’s A blueprint for modern digital government, the focus of which is very much on skills, having the right skills, investing in the profession and having people who understand what to buy and who to buy from.

“You’re not just buying a component. You’re actually buying people and skills. So how can you judge from a reputation? But if you want to buy small and medium enterprise and really encourage growth. How do you establish that those people who’s going to warrant their skills? So I think there are two aspects here one of them is purchasing.

Focusing on purchasing is one thing which will drive demand in the major enterprises and in SMEs. That’s the equivalent of the in IBM example. You don’t progress in your career unless you’re in the profession. So there’s a monitoring aspect in all of this, and I think we’ve talked about that many times. It’s a bit brutal, but it but it worked.

During lockdown the BCS created the Alliance for Data Science Professionals to define professional behaviour. It’s a collaboration between the BCS, The Royal Statistical Society, The Operational Research Society, the Institute of Mathematics, and Its Applications, the National Physical Laboratory, The Operational Research Society and The Alan Turing Institute.

“Each of those bodies can award certificates of data science, ethical use of data science, behaviour, and data science. Is there a requirement for it? Well 10% of people want it. There’s no legal requirement to do it. You can employ a data scientist today and there are many degrees that are data science associated, but whether you behave professionally is a different matter.

So the word professional becomes difficult as well. If you look at regulated professions in the Government’s list you’ll find Security Guard, Door supervisor, dentist, doctor and many others.

And there’s a good reason for that. There’s a license to operate. You don’t want your security guard doing things wrong. You have to have a license. And if you look at socioeconomic categorisation of professions, then you’re into a different game altogether. In the census there are something like eight categories in the higher profession for describing IT, there’s one for a doctor. Mainly because they can’t quite understand what this thing is: 147 skills, 15 different specialisms. What is IT?We also have more than 100,000 people in studying computer science.

When BCS did a review of how many people we thought we could address working in IT, numbers ranged from 1 million to 2 million. The understanding of what professionalism is. The understanding of how people should behave, and what you can expect from people is moving all the time.

It’s our job at BCS, the IET and other professional bodies to try and hone in on this problem.

Alastair Revell, President of the BCS

Alastair Revell, President of the BCS said he is part of a long line of Presidents who’ve been pushing professionalism for BCS and he has found ten months into his months one-year term that they have been possibly the easiest to persuade people the need for some form of change in the way that IT is practiced in this country and further afield.

“I’ve been an ardent advocate of chartered professionalism, and indeed, CITP for a very long time and it’s been an uphill battle, because it seems to be wired in people’s DNA that there are 10% who will join this sort of scheme and there are 90% that need a push.

“But I’m finding talking as President that it’s become much easier to persuade people, and I think one of the changes is driven by Horizon. That docudrama about the effects of Horizon on a wide number of sub postmasters and sub postmistresses has had a profound consequence.

“It was followed [in July 2024] by a very public outage with Crowdstrike. I think also there have been a number of challenges in and around the NHS where Joe Public basically is beginning to realise that those who practice IT actually have a lot to answer for in terms of daily livelihoods and how people actually live their lives, and how it can be disrupted in ways that affect their health, ways which affect their livelihood. And this is having a profound impact.

Revell says the challenge is to persuade the nine tenths that they need to look for professional registration. “I’ve certainly made it my Presidential theme, for my year in office at BCS, to focus on chartered and professional registrations.”

It’s creating that demand and the way that Intel actually understand the market much better than professional bodies do in some respects, if you think about Intel, they have, like most organisations, direct buyers and indirect buyers.

Most of their direct buyers are a very small group of IT manufacturers. The indirect buyers are the people like my children who buy a laptop. They won’t buy a laptop unless it’s got an Intel inside sticker, and, in fact, Intel managed to market to their indirect buyers substantially. Those blessed three notes of the Intel tune, is actually, I think, the most expensive copyright piece of music ever written per note.

And they understand the need to push to the nine tenths, so I’m quite keen on looking at ways to create that demand in organisations. We’ve been playing with the idea of introducing a registered practice which would actually require organisations to have chartered IT professionals signing off on projects.

That would start to create the demand that is desperately needed. But I think also we need to really promote the importance of chartered and professional registrations in the ecosystem of IT, so that people understand that there are professionals and there are non-professionals. And I think that that’s really, really important.

In late summer last year, I went up to Edinburgh to give a presentation about professionalism to a BCS branch and I particularly pushed on the word professional. What does it really mean? Because it’s bandied around so much today, it’s something that’s just literally used in the same way that engineer is to be quite frank.

So what does it mean? Is the question I initially posed to this Edinburgh audience, and if you unpack the word professional, its entomological root is profess. And you profess to a code of conduct as a professional. I guess it comes from more monastic times in the medieval period, where people would profess their vows to enter a monastery. Well, entering a profession, you should be professing to uphold a code of conduct at the very least, before you’ve even sort of proved your competence, which is what I believe chartered professionalism is more about adding the competence element to the professionalism.

So if you take that as a given, that nine tenths of the IT practitioners do not profess to any code of conduct. Are they actually truly professional? Or are they just people who work in IT?

But how we create the demand is the big question. For me that demand is the critical thing, and there is no magic wand. There is no silver bullet to this. But we need to build the demand with the concept of a registered practice which basically says the business gets recognised for being professional itself.

Actually, it’s very easy, perhaps, to persuade bigger organisations that they need to have this professionalism. In fact, many of them will, because a lot of their market value is probably based on their reputation at the end of the day. But in the SME sector it’s very difficult to reach, and a lot of IT is practiced in the SME sector, and it’s the supply chain to a lot of the larger organisations.

So I think, trying to create a way of passing that need for a professional organisation down the value chain is actually quite important. They have to contract from an IT pool which ultimately brings down to CITP or chartered professionals in there who are overseeing the requirement.

But I also think that you have to go all the way to the very end of this chain to Joe public, the consumer, society, who need to understand that there is an important thing about being chartered, and it is about that profession to a code of conduct and ethical practice also important.

And if people are buying their services and know that they’re getting it from a reputable source, then that will put the demand up the chain.

As part of that, BCS is introducing the concept of Chartered week at the end of February 24th to the 28. We are pushing this out to all chartered and some non-charted bodies, saying being chartered is really important and having a chartered register is really important in all professions, such as accountancy, architecture and tax.

If you’re not on that register means much more than being on it in some respects. That’s the position we need to get to. So I think by creating that sort of ecosystem is the way forward. But that is going to be a long uphill slog as it has been to produce chartered professionalism for individuals.

Summary – Professor Jim Norton

I think we’ve agreed that there’s been a loss of trust. We have to recreate that trust. I think we’ve agreed that there are mechanisms created by BCS and others with specialisms, all that panoply that’s there. The question is, what’s the next step? How do we get from where we are now? Where there is a largely unprofessional base, maybe reasonably good, but totally unprofessional, to one that would be trusted and professional.

And we’re not going to be able to wave a magic wand over a few 100,000 people and turn them into professionals overnight. So there has to be a route for doing it.

I think we’re at a tipping point and that tipping point is driven by Horizon and aided by the government, which is about to invest massively in the use of IT to promote economic growth.

Bill Thompson argued that digital media have created networked amateur or citizen journalists, some of whom have been perceived as a challenge to professional journalists. New media has also changed what journalists need to be able to do, such as to be able to communicate online, and even be more like an influencer, than an objective reporter. So, he will pose the question: What does it mean to be a professional journalist in the digital age?

Career background and perspective

I’ve been a reporter, editor, columnist, broadcaster, producer, filmmaker and contributor, most notably as the Head of New Media at The Guardian, as a columnist on BBC News Online for a decade, co-presenter of Digital Planet for twenty years, and the editor and CTO of Working for an MP since 2001. I’ve been on the boards of new media companies and charities including the Cambridge Film Festival and the National Centre for Writing.

I’ve been a programmer, consultant, lecturer, course developer, teacher, advisor, speech writer, manager, and futurist, and for the last fifteen years I’ve worked at the BBC, first trying to place the BBC’s archive at the centre of a digital public space, then on computer literacy with Make it Digital, and for the last seven years in the Research and Development group, imagining a future that the BBC might want to live in where we can delight and engage our audiences.

This has given me a valuable perspective on the continuing conversation between ways of living and the things that technologies make possible, from the emergence of personal computing to the internet, the web, mobile and now I’m one of the group of people inside the BBC grappling with the implications of generative AI.

I was one of the early adopters and advocates for both the internet and the web, and bear my responsibility for not taking seriously the need to build safeguarding into these technologies from the very start, or to appreciate just how these technologies would seep into the building blocks of society like water, cracking them as they expanded and contracted. Just as journalism has done for hundreds of years.

Past Present Future Journalism

At the end of the last century/millennium I was teaching on the master’s course in journalism at City University as an associate lecturer, covering ‘New Media’ at a time when the internet and the web were just breaking through. I’d put the first UK newspaper copy online in 1994 and built The Guardian’s first website in 1994, and five years later I was helping my students think through the implications of online publishing and hypertext, of what happens when a story can be non-linear and as long as it needs to be, about search and indexing and navigation, and about the different ways journalism might evolve.

The Guardian

In 1995 at The Guardian I sponsored the development of RecruitNet, the paper’s own job ad service. I’d seen how advertising was moving away from the paper to other online services, and felt we needed our own site. It launched in October 1996 as my last major project, but closed down the next year, and the newspaper ceded the space – and the revenue – to jobs sites and Google. Thirty years later, the online world looks very different, and almost everything that we call journalism has been folded into the set of things we experience through screens. Much of it is experienced not on the online services developed by its creators, but through aggregators, amplifiers and distortion channels, or what we can ‘social media’. This was not how it was supposed to turn out. It appears that the political journalists on The Guardian who refused to write for my nascent website were right – what we were doing on Ray Street was antithetical to the mission of the newspaper.

How Tech Changed Things

Tech was supposed to democratise, but that word has always concerned me as it rarely means what it claims, and it almost always a way of giving many loud minorities underserved prominence and not actually helping speak truth to power. What tech did was to destroy the economic model that supported 20th century journalism in one of the best examples of creative destruction and the ways the innovator’s dilemma clears out the old growth forest of an industry. (Can we scratch this analogy a bit more – have we lost the tree canopy of editorial oversight as a result, opened up the forest to fast-growing adventitious species like influencers and creators.)

Anyway, Old School Journalism (OSJ) had a fairly simple model: Journalists are employed and paid to produce material for publications or programmes that have enough money to pay them, with an editorial line, an audience, and advertisers and investors and owner. The journalists were part of a machine that involved different skills, like subbing, and a hierarchy, up to the editor. And every publication had an agenda, even if that agenda is impartiality. (Science is not a religion, but impartiality is an ideology.)

Something Changed: New Journalism?

So, what changed when first the Internet and then the Web and then Social Platforms arrived? First, it broke down the gates. Anyone can publish anything to anyone (there may be consequences of doing this). The underlying technologies (protocols and design) make the enforcement of norms impossible. Once published, stuff doesn’t necessarily go away. It isn’t tomorrow’s wrapping paper for fish & chips anymore.

There are parallels here with the emergence of New Journalism, the term used to describe a way of writing news and features that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, principally in the US, that used unexpected literary techniques to tell stories. Writers like Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion use complete dialogue, rather than the snippets quoted in daily journalism; proceed scene by scene, much as in a movie; incorporate varying points of view, rather than telling a story solely from the perspective of the narrator; and pay close attention to status details about the appearance and behaviour of its characters, using the techniques of fiction to illuminate factual copy.

The new journalism shook things up, made it possible to report on the events of the day in more adventurous ways, but is now criticised on many grounds, including a willingness to adapt the facts to the narrative, and a sense that it did not actually constitute a distinct new form of writing, but simply reflected a wide range of innovative practices at the time. I think those criticisms were overstated, and carried with them a belief that ‘old’ journalism was somehow anchored in ‘facts’ that were independently validated and unchanging, but there aren’t many epistemologists in a newsroom. But over the past 20 years digital technology has given us new new journalism, with even more concern from old-school practitioners that it is illegitimate, but a much greater capacity to disrupt than the odd essay in the New Yorker ever had.

Norms of Journalism

Let’s start by considering what the norms of journalism are anyway? How have they or could they be changed by shifts in the means of distribution brought about by digital technologies? When we talk about journalism we typically concern ourselves with news, and reporting, that part of journalism which, as Robert Lowe of The Times wrote in 1852, has as its first duty “to obtain the earliest and most correct intelligence of events of the time and instantly, by disclosing them, to make them the common property of the nation.”

According to Christian Amanpour in last weekend’s Observer, the key to good journalism is truth: “Our job is to be truthful, not neutral,” she says. When we speak, the news is full of the malign influence of Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg on the global conversation. “Of course, not everybody’s going to agree on everything and nor should they,” she says. “But unless we can agree that the sky outside is blue and the grass is green, we have no chance. What is overtaking the public square is that every single fact is now the subject of accusations of lies or bias. Zuckerberg enabling totally permissive commentary is another arrow in the heart of truth.”

I appreciate the desire to lash journalism to the mast of truth-telling as we resist the siren song of misinformation and confusion, but this simplistic epistemology and denial of context or the power of editorial choice is a bit depressing, really.

Who Tells Which Stories?

Perhaps we can go a bit deeper in looking at what do we do as journalists? In the White Album Joan Didion says: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live … We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

I’m with Joan. There is no simple definition of journalism, just constant reinvention and brief moments of consensus within certain in-groups. What we call journalism is the space between other practices like propaganda, PR, lying and science.

Journalism exists to take the events of the day and by disclosing them make them common property. At least in theory Journalism also exists to make money, to influence society, to make certain political choices inevitable or unthinkable. The drive to journalism is a political choice and all journalism is politics through another channel.

It is also for many an economic choice, a thing to do to earn money or base a business on. Journalism divides the world in space, time, topic, to create ‘stories’ that can be ‘reported’ according to the needs of the ‘publication’. Like a generative AI diffusion model journalism refines the white noise of reality into a recognisable set of elements and tropes that seem internally consistent, abstracting the world into a series of stackable stories.

But alternative abstractions are always possible, and many different stories are written every day about the same set of observed facts. Journalism is not a draft of history but the raw material for study, a class of primary source. Fuller access, easier publication, and collapsing business models create new possibilities as the old order changes, so conversation about ‘norms’ seems increasingly unhelpful. The world is changed. We feel it in the network.

What is Truth?

As we see, OSJs are concerned with reporting that tells the truth. But how do we know things are ‘true’? The philosopher in me wants to point out that we can’t, not for certain, that everything is contingent, and that we have to settle for ‘true enough’ or ‘true for now’ and not pretend otherwise.

There are things we want to hold on to as facts and we build our world models on them. But in the end everything could be revised, just at a significant cost

(this is Quine’s coherence model of truth, as opposed to the correspondence model of Tarski).

We can stamp data, or images, or anything, with a provenance claim (C2PA) and provide a chain of evidence to help us ground our stories, but in the end journalism is just another language game and reality will elude us. That’s ok, because journalism is a practice that is intended to have consequences, not really a search for truth anyway. It’s a way some of us choose to intervene in the world – perhaps for good.

And if we can’t have truth, can we have norms? Did we ever – or did we just aspire to them to give some patina of credibility to the stories told by a particular class of people, the journalists with jobs? If that’s the case, then the norms weren’t ever normative, and the emergence of digital technologies and the ascendancy of the internet just exposed journalistic practices for the convenient fiction they always were. Didion says, we tell ourselves stories. Calling them journalism imbues them with a special but perhaps underserved aura. We want to be the zeroth or first draft of history because it makes us feel good.

Heart of Darkness

Have digital technologies finally exposed the deep heart of journalism and should we just stop trying to pretend that we are special? Because if we want to be special then we need someone outside the profession to say that we’re special and that way lies registration and state approval – or withdrawal of that approval.

Perhaps it’s journalism if we call it journalism, but some journalism is just BAD?

That does not mean we abandon the belief that a well-sourced, well-reported story written with the intent to inform can’t make the world better. Because this stuff matters and is one of the protections we have against fascism, a form of government that is predicated on lying, doubling down on the lie, finding out groups, lying about the out groups, and keeping lying in order to keep power.

The New Propaganda

Lying makes Trump and Orbán and Meloni possible, as it had made Hitler/ Führer, Mussolini/Duce and Metaxas/Archigos possible in the 1930’s. If you want to know more, read Amber White’s 1938 book The New Propaganda which uses the new theory of psychoanalysis to analyse their hold on power.

(As an aside, how long before MAGA becomes a noun to describe the great leader? It’s the next step in occupying the national psyche as the despot becomes identified as the nation’s only true ‘father’.)

When I began to think about this talk I didn’t expect to get here. And I still believe in journalism as our best defence against tyranny and corruption, as a source for good in the world. It is truth-telling, even if the truths can’t be pinned down. Maybe we just need to stop being so precious and accept our role. In your body, cytotoxic T cells destroy infected cells while helper T cells send signals that direct other immune cells to fight infection. The thing we call journalism, with all its flaws, is a vital element of society’s immune system, our helper T cells. But only one element.

However, we still need to nurture them – even if some of the press cause autoimmune diseases.

What should students be permitted to use in the classroom and in their writing and other creative work? What norms should guide students and teachers in the classroom of the digital age? What will that classroom look like? How will students be judged and evaluated?

Ravi Chagger, who has been an IT computer science teacher, head of department, a specialised lead in education and STEM UK facilitator, and he’s currently serving as an assistant headteacher and IT consultant for a multi Academy trust in Thurrock, Essex, which has, since 2006, grown from one school to 12.

And joining online was Kieran Gilmurray, who’s CEO of Kieran, Gilmurray and Company, which is a globally recognised authority on AI automation and digital transformation. He’s authored 2 influential books and hundreds of articles and was named a top 50 global thought leader and influencer on generative AI last year.

Ravi Chagger – My early career in teaching

My teaching career wasn’t something I set out to do. I didn’t really have the right skills and knowledge. I did A level computing and I struggled. I found that really difficult, because there was a gap where I didn’t study GCSE computer science because it wasn’t an option. We had information systems which was more spreadsheets, databases and that sort of thing. So, I was missing the rules, the groundwork, and we didn’t get that, unfortunately, because we didn’t have the teachers.

The early part of the career saw me teaching ICT, it wasn’t actually computer science, it was softer skills, your media elements such as Microsoft applications, etc, until the last national curriculum reform in 2014 where computer science came in. I did what was needed to get children through the GCSE exams. I then left teaching in 2019, and worked in cyber security for a training provider supporting apprentices but was made redundant during the pandemic.

Following that I literally talked myself into a teaching role by speaking to my old CEO and it was around improving their cyber security compliance.

Poorly delivered primary computing curriculums

They didn’t have a clue about it if I’m honest with you. So, I started looking into the primary computing curriculums as part of my background research and realised the primary computing curriculum was really poorly delivered to an extent that some schools were actually just having less than an hour or so on an iPad or using a book where the scheme of work was arranged, and it wasn’t very effective, and the teachers didn’t have the knowledge and the skills.

Thankfully, I came across the National Centre for Computing Education, which has a bank of learning resources developed by a BCS, the Raspberry Pi foundation and CAS (Computing at School).

In our schools it was an absolute godsend, because those learning resources were comprehensive. They enable teachers to use outlines for lessons and make them their own.

And I couldn’t believe not one of our primary schools had actually implemented that or knew about it. So my first job was implementing that across the nine primary schools at the time. And we’ve had five good Ofsted reports since.

Teachers lack skills and confidence

But it’s not been an easy journey and I feel still at this level that teachers are not able to sustain that. So without me monitoring and tracking where teachers are we would be in a worse position and despite that, we’re still in a position where teachers lack skills and the confidence.

And it’s not their fault, especially in primary, because you’re having to teach 12 subjects. Secondary, you know, you’d expect a computing expert to be leading computer lessons. But it’s not always the case. Computer science teachers are super hard to find.

And I think that brings me to what my current objective is, and that’s to empower teachers. First, because if you’ve got happy teachers, you’ll have happy children that that go away and will have a sense of achievement. And that’s really what working towards and the battles faced as a senior leader for a trust is actually working alongside head teachers from multiple schools and getting them to agree to release teachers to for quality training.

Failing to reap the rewards of Continuing Professional Development

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) enables a teacher to feel empowered. And yes, it might cost a teacher being out for the day and needing cover work or a cover teacher, but the feeling that teacher gets out of feeling empowered is priceless and I’ve experienced it. And I think that’s the battle we’re facing at the moment in in order to inspire children.

Another example is Stem UK, who are based in York, and have a programme that they’re running as a partnership with schools offering access to thousands of pounds worth of free CPD. Yet I’m in a position where I can’t use this resource as I’m not being able to release the teachers. And I think it’s that pressure head teachers are under running a school.

Overemphasis on English and maths

I think another point to consider is the overemphasis on English and maths. Yes, they’re important. Yes, schools are judged on English and maths. But I feel we need to be in a position whereby digital literacy or technology is actually the middle ground, and English and maths are around. There’s a new curriculum reform to be introduced in the autumn which aims to shift towards a more balanced and skills-oriented education model with key changes including enhanced skills-based learning and greater integration of skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and digital literacy across all subjects.

However, there also needs to be changes within the schools and for me it’s the mindset of schools, leaders, teachers, and ultimately children, because they are our future.

AI is another thing that we’re trying to embrace as a trust. I’m part of our subcommittee and the feedback I’m getting from teachers is they’re not ready to embrace it yet and I don’t think we are as a trust. But I know we can automate systems in certain groups. I love ChatGpt and we’ve got Magic School, so there’s quite a few resources out there that that help me to plan for other teachers. However, I just know it needs to be embraced and introduced to a level that doesn’t create a bigger digital divide because we are still in a position where teachers struggle to send a hyperlink to pupils.

And for me, going back 20 years, we’ve actually gone a bit further back because of the cyber security implications and more restrictions now. So there’s a lot of complex issues to discuss around education.

Kieran Gilmurray

My perspective comes very much from work and the skills we need, not just children, and I would say every generation needs AI literacy. If you listen to some global figures we’re in an AI Arms race, never mind anything else. There’s so much noise around this it’s extraordinary. But one thing you can really see happening is that jobs are going to change. That’s an inevitability.

Very often with new technology you have hype and if you listen to some of the potential regarding AI then it’s going to be the most impactful thing in the world. It’s going to cure cancer, solve the world’s biggest problems from climate change to health care to energy.

But you know, everybody neglects or forgets its environmental impact, its risk, its bias and its use as a potential political weapon.

There is one thing that is going to be true though and that’s jobs are going to change. I’ve worked with AI for years. It’s not new. It’s an 80-year-old overnight success story.

The term itself, AI was born in 1956, when John McCarthy mentioned it in a proposal he and others wrote for the Dartmouth conference, they were going to recreate the human brain. Then that didn’t quite happen. But when you look at today, it’s business that’s really driving this forward. And there’s huge potential economic impact

AI is everywhere

If you’re using Netflix, in traffic management systems, border security, it doesn’t really matter where you are today, AI is there. Someone said recently, why don’t we just take AI away and remove it, and I thought well, modern society would collapse.

One study by BCG [Boston Consulting Group] introduced new graduates and compared them with AI and within six months the work quality of the two were pretty much the same. And if you’re in business and you want to suddenly develop, profit, generate, get new staff in, and get them to develop really quickly then AI brings along a tremendous amount of benefits.

AI is here and if you want to create a Chatbot something that can make a call, something that can actually engage in a human like way and genuinely in a human like way, go to Bland, if you want AI that can code 13 different languages as well as do the work of a software engineer that’s two or three years qualified, you’ve got it, these things exist.

You know, jobs are going to be massively impacted. I look at some of the research reports and some of the numbers are fantastical. But I like the World Economic Forum and its Future of Jobs report says that by 2030 170m new jobs will emerge and 92m will be displaced – a net total of 78m roles.

They tend to be right. But look at the amount of jobs that are going to be displaced in the next couple of years because of AI. The problem here is, and this is where it brings in the Education Gap, is there just isn’t the skills to fulfil it. We were mentioning a moment ago about teachers not having the skills, but I go into businesses and government groups all over the world and the one thing that they’re perennially surprised about is technology changes the world, and they don’t have the skills to actually get people into the place that they need to be, which is a permanent tragedy that AI is exposing even further.

Where is AI going to impact

There’s a real model who was not getting enough work so she created a virtual model of herself to prove that the virtual models are actually getting the jobs. And when you listen to some of these virtual people that are being created and you watch their facial expressions, they’re convincing.

New jobs are being created as rapidly as others are destroyed and the problem is there isn’t the people to do these new jobs. Ten years ago there wasn’t enough data scientists, AI architects, or those in machine learning or machine engineering.

Now we’ve got Large Language Model developers, so what are we actually going to do, how are we actually going to create all of these jobs to create this virtual, connected world? But, more importantly, what are we going to do with people?

That’s the key challenge. I heard a phrase the other day which I concur with to a good degree, where someone referred to Silicon Valley’s war on people. You don’t often hear Silicon Valley coming out describing how they’ll create new education paradigms, how they’ll get the next generation of workers ready for work. What you often hear is, how are we going to shrink workforces? How are we going to make them operationally more efficient, how are we going to get AI to remove people’s need to work at all?

AI should be a turning point for education

But we actually need humans, we actually need humans more than ever, and we need educators more than ever. And AI should be a turning point for education, because what we can do is we can race against AI and deny its potential positives.

However, if we actually work to educate people how to use AI, then I think we’ll actually been a far better place than we’ve ever been at any point in history. But we have to be careful about what we’re doing.

You know, we need to shape a generation to shape a generation. We need our educators, you know, as I said, the next world, the next generation of workers are AI natives, but we need everyone now to be work ready. Otherwise, what’s our option? We walk in? We get Gen. Z. Soon. Gen. Beta and Gen. Alpha to do all the jobs, and we dump everyone over 40 years old because they are not digitally or, more importantly, AI literate, it can’t work.

What’s the answer, then? Well, I think there’s three things. One is the training. We need to give people the tools to do the job that they require. How many teachers have access to and are using ChatGPT? How many have got Magic School? How many have the skills to use these, the funding to use these, the support, the mentoring, the coaching, and everything else? And what about the norms that we need to actually develop in this digital age? You know, what are we actually telling people to do? How are we telling them to behave?

What is it that we want from them? Because we’re doing a very bad job explaining that at organisational level, never mind any other level that I’ve come across. So what else are we saying?

We mentioned a moment ago about primary school teachers not having the funding or the time and there’s a whole host of challenges, but there’s challenges in businesses as well.

The solution to the problem is we need to develop skills, not future skills, the skills that we actually need now.

Digital literacy for me is very much: what is cyber? How do we use it? What are generative models? What is AI, what’s data analytics? What’s digital twins? You know, all those things we need just the basic skills to use the tools and cognitive flexibility is going to be key, but then again, it always has, work, life and jobs are constantly changing.

I see too many people as I coach and mentor across who have forgotten to evolve. They’ve got, shall we say, cognitively lazy as opposed to constantly striving. I say to people, ‘you can choose comfort, or you can choose growth’.

The more people choose comfort well, they tend to find themselves in a very technologically driven world falling further and further behind. It doesn’t mean that we should lack etiquette or respect for diversity online.

And constantly this choice between growth or comfort and unless we get used to choosing comfort every single time, continually set and reset our learning goals, our ambitions, how we go about things, then we are surely going to fall further behind. But we do have to be careful, because there are tremendous risks to AI, one of which I see a lot which is everybody now hands their work to AI.

However, technology has disrupted markets for the past 200 years. If you go back and consider the wheel of technology disruption, then you might as well go back a thousand years and everybody’s being impacted, not just new workers.

My warning question is why are we constantly surprised? We shouldn’t be.

Dr Kate Bradley – Telephone helplines in Britain, 1965-1999: Countercultural DIY activism to professional welfare services over the phone

Kate is a Reader in Social History and Social Policy at the University of Kent, where she teaches and researches criminal justice and social policy history in Britain from the early 20th century to the present.

Patricia Esteve-González – Cybersecurity Capacities for the Application of UN Cyber Norms

Patricia is an Oxford Martin Fellow and a Senior Research Associate at the Global Cyber Security Capacity Centre, University of Oxford, where she approaches research questions on cybersecurity from a multi-disciplinary perspective.

Dr George Zoukas and Dr Jonathan Foster – Towards Assuring Data Fairness in Trustworthy Machine Learning

Dr Jonathan Foster is Senior Lecturer, Information School, University of Sheffield and Dr George Zoukas is Postdoctoral Research Associate, Information School, University of Sheffield.