John Carrington, the founding MD of Cellnet and Archives of IT Chair of Trustees, gives his personal view of one of the most exciting developments in communications – the advent of mass mobile telecommunications.

Part one of two – 11 June 2025

Phones in cars had been around for almost 40 years by 1985, they were exclusive, bulky and, until the advent of BT’s System 4, had a push to talk button: the user had to say “over”. They were limited in number and range by the technology and available radio frequencies. Demand had always outstripped supply, such that by 1983 in the UK there was a strong black market for phones in cars.

So, what changed with cellular? The secret is in frequency reuse enabled by advances in computer technology. It all started with Bell Labs in the 1960s. The invention of the transistor and the microprocessor – and advancements in these technologies by the mid-80s – allowed for the complex task of tracking mobiles on the move to happen.

Competition in telecoms

In the UK Margaret Thatcher’s government promoted competition in telecoms with Sir Keith Joseph, her policy guru, heading the Department of Trade and Industry. Competition was the name of the game, monopoly was out. In 1982 the UK government announced there would be two new mobile network operators using the new cellular technology who could not sell handsets or service to customers, this would be done by resellers.

This approach was designed to boost competition and involve more business in the market as to have more than two network operators would have greatly diminished the capacity of the radio frequencies, as each operator needed their own within a finite range.

The newly created regulator Oftel would judge the competitive bids for operating licences. BT was not guaranteed a licence although it had been planning for a new system involving cellular to be called System 5. The government insisted BT had to find a partner to bid. Securicor emerged as that partner with a 40% share in in the proposed operating company, Telecom Securicor Cellular Radio (TSCR).

Why Securicor? Diversification from their security carriage business had led to selling and installing pre cellular mobiles. They also had an extensive private mobile network based on their own need for radio communication. A licence was awarded to a joint venture between Racal, Millicom and Hambros in March 1983. That’s when I come into the picture. I was appointed to lead the BT/Securicor joint venture in May 1983 just as Racal’s licence was issued. I had worked in the GPO, Post Office and British Telecom since 1967 latterly as Director of Commercial Strategy for BT’s International Division.

Adopting a standard

One of the first things the industry needed to do was to adopt a standard which determined how the new networks would work. The UK was driven by government industrial policy to help industry with an opportunity for exports. Things were tight as the licences required commercial services to be launched in 1985.

A great deal of resource from BT Research, TSCR the DTI and Racal, was applied to the work and a standard emerged based on the US AMPS model only just emerged in time for manufacturers to meet the deadline for service to start on 1 January 1985. A key decision was that the calling party would pay which was unlike the US approach. With my BT background I felt that people being called by a mobile may not accept the call if they had to pay. I think the US policy slowed take up there compared with the UK.

We were entering uncharted waters and the relatively low market forecast at the time reflected that the scepticism I met in 1983 when explaining my market vision to the City and the media. 1984 proved a key year for understanding the potential of mobile. Nordic networks had proved very successful, but we really had little idea of likely UK demand.

An opportunity to put a toe in the demand water arose when TSCR took up the challenge to provide a pilot network for the London G7 summit in June. There were six overlapping cells covering central London, Gatwick and the A23 between. The TACS standard was not ready for manufacture, so we used a modified AMPS version at the TSCR allocated frequencies.

The creation of Cellnet

As a test of the technology and UK customer intent, the pilot network was fantastic. I chose the time to have our first ad in the Financial Times featuring Ronald Reagan. It launched the network brand Cellnet. Using the President in this way was sailing close to the wind but the US Embassy liked it and asked for copies. That one ad produced 15,000 responses.

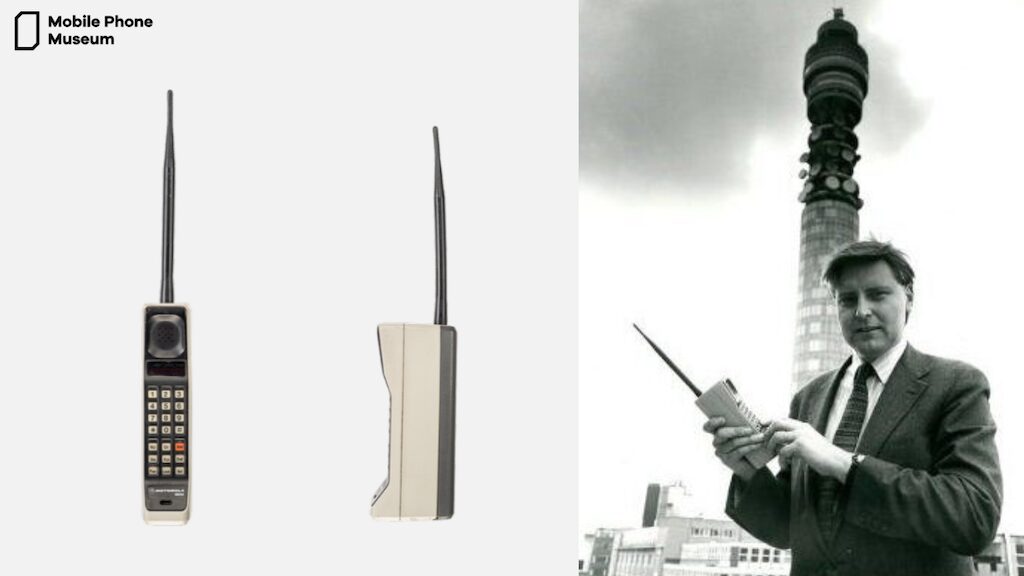

After the summit we let potential customers try the offering for a few weeks. We used carphones and 10 Motorola hand portables. I spent a lot of time with potential customers. Everyone who used a mobile wanted one. I asked for and got more money to invest in the network. I also realised BT, despite its huge network, lacked the necessary project management skills to provide a network in the time required. We brought in WS Atkins to help us; they were used to project managing motorways and nuclear power stations. It was a key move which speeded up the network build.

Cellnet used Motorola’s unique position in the supply of handheld phones to build the world’s first network to support them. Because of the power limits of handheld devices far more base stations were required. At £3,300 each we could not get enough supply to meet demand when the network went live.

I took a gamble and tried to launch on Christmas Day 1984 on the Noel Edmonds show. Sadly, one of our guys forgot to press end key on the Motorola handheld Dynatac and Noel could only get an engaged tone when he called Johnny Morris in Regents Park from the BT Tower. Cellnet launched in early January 1985. Demand was fantastic setting the scene for the next challenge – taking the service beyond Dover and the development of a European operating standard and GSM, which I’ll cover in my next blog.

Related Content

From bricks to bendables: 40 years of Mobile Phones

Going Mobile exhibition explores 40 years of mobile phone technology

Celebrating 30 years of the GLOMOs: The history and future of mobile phones

The story of the Internet from the pioneers who made it happen

Arm marks 40 years since the development of its first microchip