John Carrington, the founding MD of Cellnet and Archives of IT Chair of Trustees, gives his personal view of one of the most exciting developments in communications: The Mobile Phone Revolution.

Part two of two – 3 July 2025

In my last blog, 1985 and the mobile phone revolution in the UK, I covered my personal experience of founding Cellnet (now O2) and taking it to launch in January 1985.

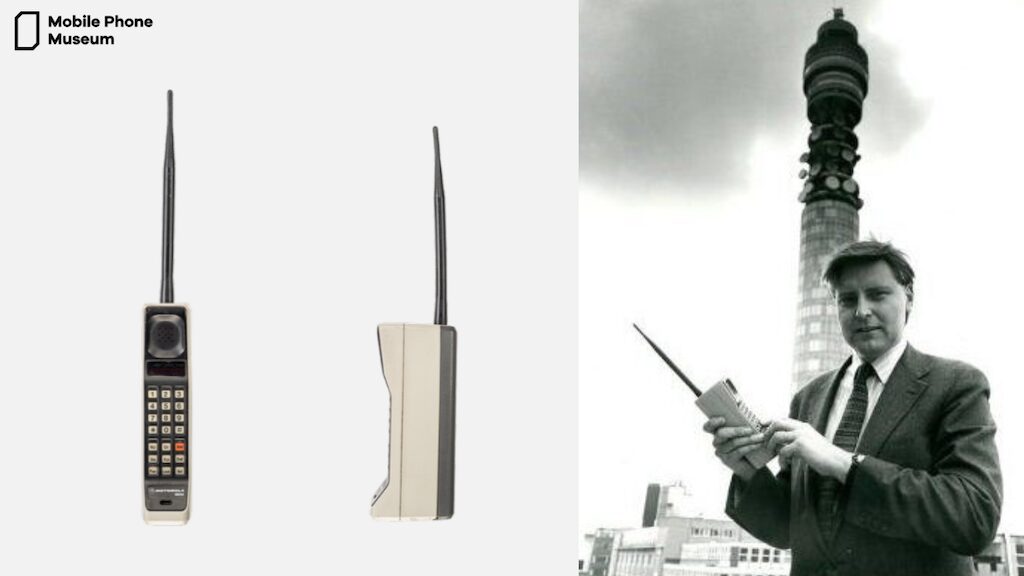

One concern by all the commentators at the time, as well as funders, was potential demand. My concerns had been overcome when we used the system Cellnet put up for the G5 meeting in London in June 1984 to demonstrate cellular to customers after the heads of state and government had gone home. Everyone who used the handheld or in car sets wanted one, no one asked the price.

From launch I used to visit the exchange every evening to check on numbers who had registered for service. After three weeks I stopped doing this as the numbers far exceeded our forecasts.

So, the race was on. The networks spread fast to meet the coverage conditions in the licences. Cellnet quickly opened in Birmingham and on the M1 motorway to London.

International connectivity

The fast UK coverage roll out soon raised questions from customers about international connectivity; there was none. A pan European standard had been under discussion for since 1982 in a study group called GSM. It had made very slow progress, bogged down by national industrial policies.

I started to explore cooperation in Europe early in 1985 with a visit to Paris to meet my opposite numbers from France and Germany. Advising the DTI ahead of my visit I had a firm note saying ‘agree nothing’. Nothing should undermine the export potential of TACS – the UK cellular standard.

In my new role as Director of Mobile at BT I was convinced that the future of mobile was tied up with an international agreement on standards. My experience in BT International had shown me how potent agreements on standards could be as a stimulus to growth in telecommunications.

The success of the new UK cellular networks and the fact that continental industrial interests could dominate a new pan European standard began to cause a review of policy to take place at the DTI. I think my lobbying helped in a small way with this.

Rapid customer growth and intergovernmental agreement

Rapid customer growth in 1985 and 1986 was stimulated not just by meeting pent up demand but also by the actions of Cellnet and Vodafone aimed at creating competitive advantage. In March 1986 BT cut the price of its cheapest car phone by 50% as part of a rental bundle. The same approach is still around today.

With the success of the cellular market in the UK in 1985 the DTI and Vodafone agreed that they needed to be part of the GSM plan.

GSM was to be a digital standard and that involved a huge amount of work. Resource to do this had been scarce until in 1986 when a permanent nucleus was established initially in Paris with staff seconded from European telecom operators. I’m proud to have seconded a key member of my team, Bernard Mallinder, who been technical director at Cellnet. Progress on the technical standard started to be made

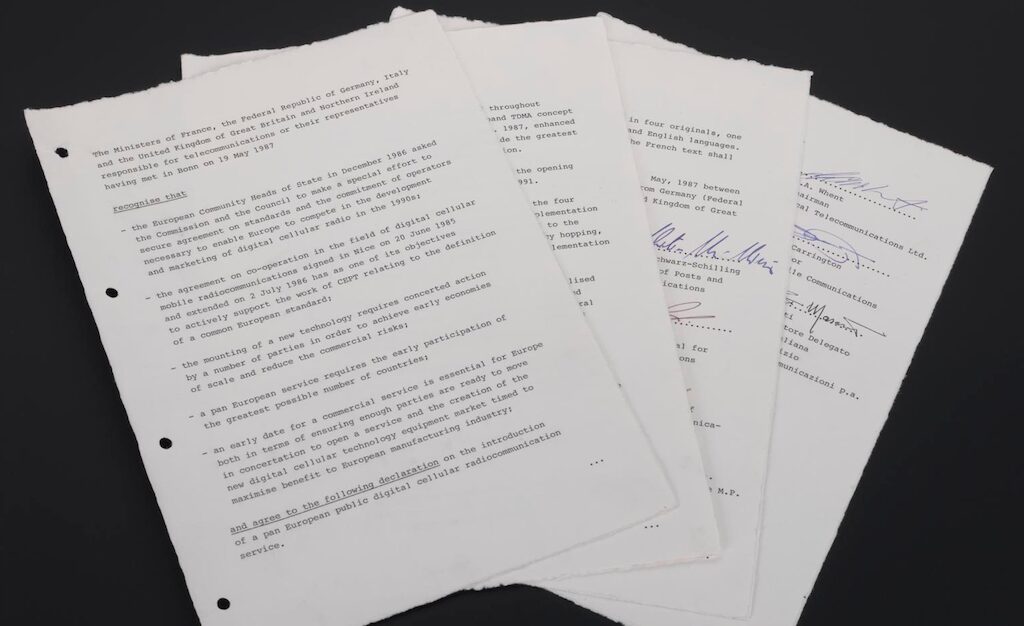

Political agreement was as important as technical agreement in establishing GSM. In 1987 discussions between UK, France, Germany and Italy led to a key four party inter-governmental agreement to support the development of GSM. The standards work would be supported, and research shared. I was a signatory to that agreement

European memorandum of understanding on GSM

The political accord was followed by European operators signing a memorandum of understanding on developing GSM in September 1987. In 1988 the two operator per market model was adopted as well as open interfaces between operators. The GSM specification was ready for manufacturers. The GSM digital standard had been hard to establish but so was the challenge to manufacturers. In 1991 German networks were ready but they lacked the handsets. At the February 1991 GSM Congress in Cannes buttons were issued showing the initials GSM with the subtext of God Send Mobiles.

This logjam for mobiles was broken in May 1991 when the technical issues for manufacturers were solved. The UK’s Orbitel was the first. Motorola launched its GSM mobiles in September 1991. Then Nokia hit the market in November 1991, seemingly from nowhere, and was soon the market leader.

Digital handsets

The next stage of the mobile revolution brought a digital handset capable of developing into today’s smart phones. The phone and the customer identity were separated with the SIM card. Text messaging was enabled, marking the beginning of the end for radiopaging outside hospitals. The large market throughout Europe enabled big volumes in manufacture and so brought down prices, and ownership was moving from the company to the individual.

At the time, the world was watching the development of GSM. For example, I was invited to Beijing in late 1988 to brief the Chinese on the European standard just as it was being challenged by the US who were developing their own standard. The Chinese chose GSM along with most of the world – perhaps I helped, who can say.

Looking back, cellular has been transformative. There are now about 7.5 billion mobile users in the world with an estimated 18 billion devices and smartphones have changed society. I am proud to have been involved in the early days of a major revolution in the way the world communicates.