Doron Swade is an engineer, historian, museum professional and scholar who publishes and lectures widely on the history of computing, curatorship and museology. He is the author of more than eighty articles and four books. He is a leading authority on the works and life of Charles Babbage. During his tenure at the London Science Museum he directed, managed, fund-raised and publicised the construction of the first mechanical calculating engine from original nineteenth century designs by [Charles] Babbage. In 1989 he founded the Computer Conservation Society and in 2009 was awarded an MBE for his services to the history of computing in the New Year’s Honours List.

To cope with the isolation Doron felt amid the chaos, he learned to build things and started his love of electronics. He explains: “From the earliest age I can remember being interested in electronics. Where that interest came from, I don’t know, there was nobody else I knew who did electronics.” Doron would buy electronic components, military headphones, quartz crystals, from an army surplus electronic shop. He adds: “I had a book published by Philips, the Dutch electronics lighting company now, and in it were projects, transistor projects, and I would work through this book.”

When a friend’s father’s radio shop closed down, Doron was invited to take what he wanted; he salvaged valves, variable capacitors, resistors, capacitors, knobs, and a valve tester with its manual. He made a transistorised transmitter which was later used in a school prank and a baby monitor so his cousins could listen into their baby. He says: “It wasn’t just the design of these things and the functioning of the components, it was the craft of the manufacture, it was how the plastic, the PVC wires were bent round corners, it was the colour combination of the wires, there was an aesthetic to how you built something properly, and that carried all the way through. Another aspect of that period, which goes back to what eventually became quite influential, was the idea of restoring and conserving things, being a curator. That must have been an ingrained, and inherent in me, from the earliest age.”

He adds: “Building things, making things, was an environment of a kind of security, it was a kind of meditation where – I won’t say nothing surprising won’t happen – but however difficult human relationships were, the world of objects, the world of artefacts, the world of machines, there was an inherent logical grammar to it which was the comfort.”

Doron attended a private day school where he studied physical science, mathematics, Latin, English, Hebrew and Afrikaans. He says: “I loved Latin because of its structure, it gave me more insight into English than almost anything else. Physical science was my natural language, I had an inherent affinity with it. Mathematics I loved although, in retrospect, I don’t believe I’m a natural mathematician because, to me, a mathematician is in some sense like an artist and that is, you cannot acquire what they have, they can see meaning in abstraction. I can’t see meaning in abstraction, I have to have a relationship between the abstraction and something physical. … It was only long afterwards that I realised that I was not a natural mathematician, I was an engineer at heart and the language of engineering is mathematics, but that was long after I left university that I actually figured that out.”

Doron says the experience taught him how to command respect. As a radar mechanic, Doron worked on mortar location radars of which there was only one in the country and with only one person qualified to instruct on them. Unfortunately, the instructor was posted just as Doron and his team were sent to his camp and so Doron spent the time studying vacuum technology and preparing for university.

In 1965 having finished his national service, Doron went to the University of Cape Town to study Light Current Electrical Engineering Doron says: “I was of the last generation to design with vacuum tubes, it was a transitional period so we learned about transistors, we designed with transistors ( h-parameters), and my thesis in ’69 used TTL chips, integrated circuits. It was unbelievable, the most demanding course there, it’s four years of physics and maths, it was very demanding and there wasn’t a day off.”

Having completed his degree, Doron went onto study for his Masters in control engineering.

It was while doing his Masters that Doron was introduced to computers via a friend. Doron says: “The computer was a Varian 620i which is a machine with 8K core [store] memory, with a teletype paper tape input and a three-pass assembly system and they wheeled this into the laboratory. I started looking at this thing and within a very short time I transferred my thesis to the computer. The thesis was in control engineering called System Identification with M-sequences using a small digital computer.” For Doron, who describes himself as an autodidact there was no distinction between hardware and software. Programming was just the top end of a process that was rooted in the physical hardware.

Doron’s own department then ordered the same machine. Doron explains: “So, my first connection with a computer was how do you fix a computer. I had to work out how this computer worked in order to fix it which I succeeded in doing from first principles, in some sense … of course, one had some contingent knowledge of that particular machine … and I ended up running the departmental facility which was the facility provided by this machine. There was a natural affinity with this: programming to me was like mathematics, it was absolutely logical, the structure of it all, but the thing I discovered which influenced me a great deal later was what the nature, psychological nature of programming was. It can be absolutely obsessive, that I would spend hours and hours writing programs.”

At the end of his first year, he was given a thesis topic by Gerd Buchdahl, a Kant expert, who had himself given up on solving a particular problem. Doron says: “It was a metaphysical proof of Newton’s Law of Action and Reaction, Newton’s first Law of Motion: action and reaction are equal in the world and Kant has a metaphysical proof which is two and a half pages long or three pages long. I took this problem and I spent a year locked in a room, I could not make head or tail of it.” Eventually, Doron submitted his thesis, he adds: “Two of the three examiners couldn’t understand it and failed it. … That was probably the most intellectually challenging thing and probably my finest and greatest achievement was trying to prove this thing and not cracking the fact that it couldn’t be proved.”

Having done some consultancy for Atkins into mini-computers in the medical environment, Doron attended a conference at Wadham College in Oxford about mini-computers. John Gedye gave a lecture which Doron says completely blew him away, so much so, that Doron asked John if he could work with him. In 1974, Doron applied to the SACSIR, the South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, and got a grant to work with Gedye on computer-assisted human decision-taking, (Man-machine studies) at the University of Essex. A year after joining John’s department, John went to work in the US and Doron was supposed to join him. Unfortunately, the college blocked his visa application and as a result Doron ended up applying for jobs elsewhere.

In June 1975, to earn some money, Doron applied for a fixed six-month contract engineer role at the Science Museum to work on the computer gallery that was due to open in December. Doron was interviewed by Arthur Rowles, head of the department. Doron says: “He took a punt on me, he saw something in me that was worth it, he took a risk on me.” Doron worked for six months designing exhibits for the computing gallery. He adds: “We worked hard, and I loved it, I couldn’t believe people paid me for it. I remember walking down Exhibition Road outside South Kensington, having struggled with philosophy and having bent my head round the stuff, that was the worthwhile stuff, to solve problems and I thought, ‘I didn’t get paid for that, and I walked downhill and thought of all the stuff I didn’t do, and they’re paying me.’ It was extraordinary.”

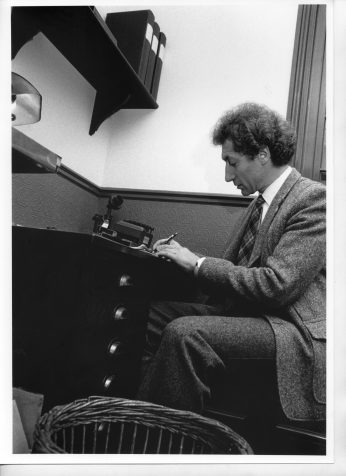

Doron remained in the role of electronics design engineer on contract until 1983 when he decided to take a pay cut and become a permanent member of the team. Doron became Section Head and spent a further two years working at the museum devising exhibits to explain complex scientific theories and inventions to the public.

Doron says that as an engineer in his early days at the Museum, he learned to make sure his designs did not break down, he explains: “You’re crawling on your knees in dusty cases behind the public panels to fix anything that broke, that is why I designed things that never broke. I designed things that were self-restarting, that had self-correction in them, that monitored themselves, that re-booted themselves after every operation so that the program was always refreshed, developed a complete set of techniques for continuous unattended operation in public environments – so that I would never have to crawl around replacing light bulbs.”

Doron says: “I was privileged and honoured and hugely fortunate to work [as an engineer] in the Science Museum which has an educational mandate and use electronics in an environment that was richer than electronics. So, I could get involved in the exhibits. But I wasn’t authoring the exhibits because the curators authored the exhibits; I was implementing them.”

However, that changed when in 1985, the role of curator of the computing department was advertised and Doron, after much soul searching, decided to apply. Doron says he was in awe of curators and that he saw it as a ‘gentleman’s job’ in English culture, because they knew about culture and history. He says; “I was an engineer, and as an engineer I was deeply ignorant of things outside engineering. I was awed, but what I didn’t know I was a better qualified as a curator than many – I’d done history and philosophy of science – a curator of physics in those days was a physicist, they hadn’t done philosophy. A curator of medical sciences had been a doctor. And here I was, I’d been in Cambridge for two years studying metaphysics and philosophy of science. So crossing the tracks from being an engineer to being a curator is a fundamental thing in this culture, possibly in other cultures but certainly in this one.”

The prize artefacts in the computing collection comprised two categories: earliest prototypes of electronic computers from the late forties and early fifties, as well as artifacts relating to Charles Babbage’s efforts to build mechanical computers in the nineteenth century.

In Doron’s reading of the many Babbage books owned by the Museum one fact struck him; Babbage had failed to build any of his engines. Doron was intrigued and says that “within weeks or days of that thought – why hadn’t somebody built an engine? – Allan Bromley appeared on my doorstep.” Allan Bromley was an Australian computer scientist who visited the museum every winter to study Babbage’s drawings. Doron says: “He believed that Difference Engine No. 2 could be built … in his hand was a proposal addressed to Dame Margaret Weston (Director of the museum) that the engine be built in time for the bicentenary of the date of Babbage’s birth 1791. … That was the start of the whole building of the engine. So, for the next seventeen years, in addition to everything else I did, I picked up the challenge of getting the Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2 built, which would be the first complete engine built to Babbage’s original designs.”

The museum completed the calculating section for the bicentenary in 1991 and then subsequently, eleven years later finished the engine by building the output apparatus after raising additional funding.

In 1992 Doron went to Siberia to acquire the BESM-6 [a Russian supercomputer] for the National Museum of Science and Industry. He also returned with various generations of Kronos motherboards, an AGAT, which Doron describes as “the Russian Apple knock-off using the same operating system”.

In 1993, while still working at the Science Museum, Doron started his PhD examining the utility of calculating engines. Doron’s research looked at the thoughts of Babbage’s arch-rival George Biddell Airy, the most prominent civil engineer of his day, who was vehemently opposed to the utility of engines. He says: “The study I did for the PhD was ‘utility’, how did people formulate, how did they express utility, why was Airy opposed to it, because almost everything quoted of Airy is that Babbage’s engine was completely useless and the sooner it was finished with the better. The question is what’s behind that? Is this just the dismissiveness of a rival, is this professional jealousy, and it isn’t. I unpicked, from new correspondence about calculating machines that Airy was involved in and new archives in Cambridge, and then rebuilt his position in relation to his pronouncement about Babbage.”

In 1998, Doron was project director of Japan UK and curated the travelling exhibition, Treasures of the Science Museum, in 1999. The exhibition toured in Japan, including Kobe, Kitakyushu and Tokyo. The project was funded by Yomiuri Shimbun, the most widely read Japanese newspaper and was aimed at expressing the technological co-operation between Japan and the UK. The exhibition consisted of fifty of the most valuable or historically interesting objects in the Science Museum’s collections. It was a huge success, Doron says: “The experience was wonderful. The cultural issues were glorious, I mean, the negotiating things were priceless to actually decode what was going on, and it was hugely successful for everyone. The gate far exceeded anything anyone imagined and when I went to the director after it all happened and said, ‘Well, there is this contract which says we get fifty-fifty’ he said, ‘Just wave it aside, these are friends’. He didn’t care about that. It was a massively successful exhibition and all the objects came back successfully which was a big relief.”

Computer Conservation Society

In 1989 Doron founded the Computer Conservation Society. The idea came to him as a result of coming into contact with many different experts, and people passionate about computers who were individually preserving machines around the UK. Doron says that he would frequently receive calls from people asking if the museum would be able to take on a machine that they had restored or saved.

He explains: “As a curator you are responsible for the national computing collection and the point is that no single person can be aware of the whole field and it is people’s individual experiences of particular machines that makes them meaningful. … I’m hugely grateful to people in the industry because they educated me. They would come to me and say, ‘You have to save this because ..’ and I’d say, ‘well, why is it significant?’ and they would tell me. There’s no way I could have known that machine was significant, I’d never heard of the machine.”

After visiting and speaking with many such experts, Doron realised that they were frequently isolated from other people who shared their passion and expertise. He adds: “So what we needed was a social organisation, a club, where people from the IT industry and the computing industry could share their meanings of their professional experiences and their personal experiences. The seed of the idea of the computer conservation society was to create a social organisation that would marshal and harness these people and create an organisation that they could join.”

Doron presented a proposal to BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT (then known as the British Computer Society) and the founding of the Society was approved. Tony Sale and Roger Johnson supported the idea. After the meeting Tony Sale visited Doron and said ‘I was at your presentation, you pushed all of my buttons, I want to come and work with you.’ Doron adds: “That was it. I had funding for the exhibition and so I created a post for Tony to make the Computer Conservation Society, to assemble this group of people that would restore these things to working order and he just took off, absolutely took off.”

The Ferranti Pegasus was one of the first computers chosen to be restored to working order by the Computer Conservation Society. Doron says: “Pegasus became the flagship project for the society because we didn’t know whether you could restore these things to working order and we did, we succeeded. It was a huge staging post of credibility and confidence that this programme of restoring old machines to working order was viable.”

Royal College of Art

In 2003 Doron was awarded his PhD at UCL and left the London Science Museum and in 2004 he became a Visiting Professor of Interaction Design at the Royal College of Art. He says of the experience: “Interaction design intrigued me hugely because I’d never formally trained in it, but I had been designing working exhibits and formulating perceptual aspects of the experience of the visitor or experience of the user of an interactive design. It was wonderful, it was quite short-lived, I was completely bowled over by the creativity and the quality of students there, it was mind-blowing what these guys came up with. They did not have engineering disciplines to the extent that I would have liked, you need to understand materials to make new things, and I felt that that discipline wasn’t there, but the creativity was absolutely mind-boggling and that was hugely rewarding. The other thing that was massively rewarding was holding seminar sessions with them because they had such diverse backgrounds.”

In 2006, having stayed in touch with several trustees from the Computer History Museum, Doron was invited to be Guest Curator at the Computer History Museum, commuting between the UK and California to curate a major exhibition called ‘Revolution; the first two thousand years of the history of computing’.

He says: “I went there for stretches, I commuted to California, in Mountain View, the longest I spent was seven months, I spent stints of three, four months, came back for a month, went back, and again it was culturally terribly interesting because their history of computing is entirely different to our history of computing. … It’s their history that’s going to be told because there’s a rather unreconstructed view of what history is. I found it utterly fascinating because your job as a curator is to tell the story of their times using material artefacts.”

In 2008 Doron curated a second exhibition called; ‘Another Age must be the Judge’ which focused on Babbage and featured his second Difference Engine a duplicate of which was in private ownership. Doron chose the title for the exhibition based on a quote by Babbage who had become deeply embittered and disillusioned by the fact that he received no recognition and that people didn’t understand what he could see about the potential of computers.

Doron says: “Ada Lovelace is another way in which to get a computer historian to leave the room, because so much has been written about her, some of it, is well-founded and other is not well-founded.”

Ada Lovelace is today presented as the first programmer, a mathematical genius, having had a major influence in the design of the Analytical Engine, and a prophet of the computer age. Doron explores each of these claims, and summarises: “What she is, and deserves all the credit for, and more credit than she gets for being the first sodding programmer, is the prophet of the computer age. It was she who saw something that Babbage did not see. She saw that the value of computing was the ability to manipulate, according to rules, representations of the world contained in symbols. … So, a prophet of the computer age, I’d say yes, and I think that’s a lot more important than saying you wrote the first program because quite clearly you didn’t.

“I have absolutely no expectation that the world’s perception of Lovelace as being the first programmer will ever change because it’s not to do with history, it’s to do with the social and our sociological need for people to have a representative, an advocate of a particular viewpoint, in relation to science. That is at the expense of history, but that’s how it is. Lovelace, was very important to Babbage and she was an extraordinary person and I would frame her massive contribution in that she understood, in ways that nobody else did or was able to articulate, the potential of computers to be relevant to the world because of manipulations of representation in numbers.”

Plan 28 is a charity established by John Graham-Cumming, a computer scientist, with the aim of raising money to build Babbage’s Analytical Engine. John invited Doron to join the team which includes Tim Robinson who has built Meccano versions of the first and second difference engine.

Doron believes that the charity will be able to raise the money but adds: “Money is not our restriction right now. The question is, to understand the designs which we could not reverse engineer. There were questions that we could not answer from the known famous drawings which were the ones we had access to. We now have access to the whole lot so what we’ve been doing is going through the entire archive (7,000 manuscript sheets) to find every reference [to a topic as well as] to his mechanical notations, and decode them.” Funded by a 3-year Leverhulme research grant Doron decoded Babbage symbolic language, the Mechanical Notation. Of the method, Doron adds: “Now we have an engine which a few of us understand intimately and know what every part does, and we have a Notation which describes what every part does, using crazy cryptographic symbols, and we can now decode.”

The aim of the charity is to build the Analytical Engine and this remains its main objective. Doron says: “What Plan 28 is right now, is a research project to put us in a position to specify an engine that will be historically meaningful from Babbage’s analytical designs. That’s the aim of the project and that is what we are currently doing. Whether it gets done in my lifetime I don’t know but what would be massively satisfying is to crack it, is to actually understand the Analytical Engine in ways that Babbage intended.”

On creating balance between his theoretical role as a scholar, curator and manager and his design engineering and practical skills, Doron says: “I’ve never tried to balance everything, I’m a useless balancer because I’m obsessive, so I will work for six months and work myself to exhaustion on one thing because I find changing difficult. Fighting mental dispersion is difficult, I get interested and excited by too many things, which is why I have to have a really convergent discipline to do just one thing which is why the PhD was very self-satisfying.

“I’ve never seen the difference between being a curator, being a manager, being an engineer – they’re all to do with a quality of judgment you bring to the appropriateness of what you are creating.”

“I would be more assertive. I was much too apologetic. I was not nearly confrontational enough. I wanted to be liked too much to actually … so I buried a lot of what I thought and wasn’t nearly articulate enough and a strong enough advocate for things.”

Doron believes that the challenges faced by museums include the need to maintain the continuity and depth of collections and to ensure that those curating are subject experts. He says: “The huge privilege of being a curator and the value of a museum is to use the permanence of substance to create a material record of technological change. The legacy, the residue of our tenure of curatorship, or a museum, is in the physical, in the collection. And it’s the permanence of substance, things that outlast us, that is the legacy of the story of our times, so we need to tell the story of our times leaving physical artefacts as evidence. The point at which you cease to have subject specialists makes the story very difficult to tell. The challenge to museums is, how do you protect the future of collections to ensure the same, almost eccentric authority, as in the past.” With the number of items collected falling, Doron says the biggest challenge to museums will be in the future; he says: “what will future generations tell of our age as a result of the material record that our contemporaries now have left upon which they are to construct our histories.”

“Try and apprentice yourself in a major national institution where the traditional curatorial practices are still part of the culture. … Get into a big organisation where you can experience the kaleidoscope of skills involved in museology, of conservation, of restoration, of documentation, of management, of project work and all that, exposure.”

“I would say, always try and do good work. … You have to learn the techniques for reconstructing the best story you can from the available evidence, which may be fragmentary. Learn that from the people who do it best.”

Throughout his career Doron has worked as a consultant with numerous organisations including; Atkins, Felix Learning Systems, Interactive Teaching, Webster software, and Simtec in America, amongst others.

Founder of the Computer Conservation Society

Awarded an MBE for his services to the history of computing in the New Year’s Honours List 2009.

2017 Doron was presented with the Computer Conservation Society Lifetime Achievement Award.

2018 Doron was awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Holloway University of London and became an Honorary Fellow of the British Computer Society.

interviewed by: Elisabetta Mori on the 8th May 2019 at the London Offices of BCS

Transcribed by: Donna Coulon

Abstracted by: Lynda Feeley