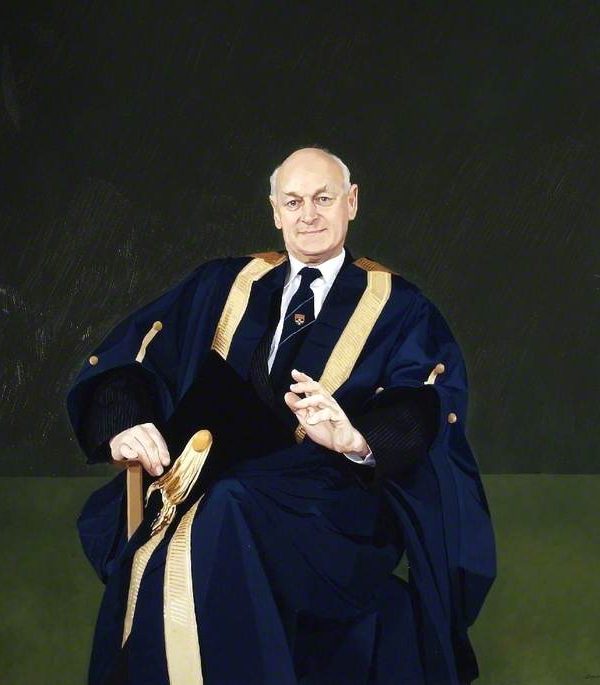

Ewan Page is a British academic and computer scientist, and among many other things the former vice-chancellor of the University of Reading.

Today he welcomed Mark Jones to his home near Bath to share stories of his life and career.

Ewan Page was born in August 1928. He attended Humberstone Junior School, near Leicester, followed by Wyggeston Grammar School for Boys where he met Mr J W Hesselgreaves, whom he describes as ‘one of the outstanding mathematics teachers of the time’.

Hesselgreaves encouraged Ewan to try for an open scholarship in mathematics at Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1946/7. The transition to maths at Cambridge was more challenging than school, Ewan says: “You realise that while you might have been pretty good at school, when you get to Cambridge there are always people who are much brighter than you are.”

In his third year, Ewan was able to select a number of advanced courses and alongside “everything to do with mathematical statistics” he also chose a new course entitled Programming an Automatic Computer which was given by Maurice Wilkes. At this time the EDSAC was still being built and computer science was not recognised as a formal subject. Ewan says: “For many years they (the university) wouldn’t give Maurice Wilkes a chair, which I think was quite wrong. When he took the chair, he decided on the title, not computer science, but computer technology. Computing wouldn’t be regarded as a science then.”

At the end of his degree in 1949, Ewan had expected to return to Cambridge to do research in mathematical statistics, however, due to an administrative error during a changeover of staff at Cambridge, his name was not submitted for a grant and Ewan was called up for national service in the RAF. At age 21, after being commissioned, Ewan went to teach mathematics to air signals officers at the RAF Technical College at Saffron Walden.

During the two years Ewan was in the RAF, Maurice Wilkes and his team completed the building of EDSAC, and got it working. Ewan explains: “By the time I returned in 1951, it was just about doing useful work. In 1952, I needed to do quite a lot of calculations for one of the inspection schemes that I had devised, and so I sought to see if I could work on EDSAC.”

Having got permission to use the EDSAC, Ewan taught himself to program as everyone did . He adds: “Then you wrote your program. You punched it out on five hole paper tape, twice, and put it through a comparator, and if the comparator didn’t stop it, you had one of those long tapes which you wound up, put a rubber band round, attached a form saying what had got to be done and you hung it on one of a row of hooks outside the computer room. The following day perhaps it would be returned, almost certainly saying that it hadn’t worked. So, you tried to correct it, punched it out again, did exactly the same thing and went backwards and forwards until you had got your program right. Then at that stage, it would be run for you.”

Ewan discovered that if he switched from the Statistical Laboratory as a research student into the Mathematical Laboratory, he would share a room with some other research students and he could get trained to run the computer after the engineers had gone home, if it still worked.” Ewan shared the space with Keith Eickhoff, a structural engineer, Don Leigh, a Canadian, who was being supervised by D R Hartree and Sandy Douglas, who eventually became a professor at Leeds, and a President of the British Computer Society. He adds: “One of the other people that I was down to share EDSAC with spent most of his time visually comparing two five-hole punched paper tapes, because this was quicker and more reliable than the automatic comparative upstairs. I didn’t know him at all well, but his name was J C Kendrew, later Professor Sir John Kendrew, Nobel Prize winner for finding the structure of haemoglobin, which was evidently what he was working on at the time, those nights when we shared that machine.”

Ewan completed his PhD thesis entitled ‘Continuous Inspection Schemes and Monte Carlo Methods’. He was awarded the Rayleigh Prize for his work on the continuous inspection schemes.

After completing his PhD, Ewan took up the newly established lectureship in mathematical statistics at the Durham Colleges in the University of Durham. During his time there the two elements of the University , Durham Colleges and King’s College, Newcastle upon Tyne in Newcastle, combined in order to stand a better chance of gaining a grant from the University Grants Council to purchase a computer. In 1956, Ewan applied for the position of Director of the new computing laboratory. Initially, he was unsuccessful, and the role was offered to Sandy Douglas, who opted to go to Leeds instead and Ewan was approached. He says: “When I was appointed, I made the point that it should be an academic department as well as a service department , partly to be able to get enough people to form a core who could do some research because otherwise there would be penny numbers, and nobody would be able to support anybody else. It really wouldn’t be very good at all.”

Ewan proceeded to build his department. He appointed a lecturer in theoretical physics who wanted to transfer to computing, a research student from the same department, and Paul Samet, who later became a President of the British Computer Society and Elizabeth Barraclough, who had been working on a Pegasus machine and who eventually became Director of the Computing Centre. Having built his first team, Ewan’s next task was to establish a computing service and start a postgraduate diploma in what he called ‘Numerical Analysis and Automatic Computing’.

Ewan says of the department: “We were certainly very different (from other departments). Particularly, because initially we were a university department, rather than a divisional one which meant that the money for the computing laboratory came out of the grant to the university, before it was split between Durham and Newcastle . I wasn’t in competition with all the people in Newcastle with their engineering requirements or with those in Durham. Eventually, we were teaching mainly in science departments, which led to me becoming the Dean of Science, but as I was not competing with any of them for the funds, it was a very pleasant time indeed, and somehow or another they trusted me, and I think that was initially the start where, when Newcastle became a university on its own, and we were transferred into it, that I then became Pro-Vice-Chancellor and eventually Acting Vice-Chancellor before going moving to Reading.”

In order to gain further funding, Ewan also started to build links with industry obtaining money from Parsons, the marine engineering people, which guaranteed them a certain amount of time on the machine, and some from Parmatrada, which was a marine research establishment on the Tyne. The university also sold time to Procter & Gamble which had a research establishment nearby.

As well as finance, Ewan was keen to attract expertise and interest locally and so took the opportunity to start a regional group through the newly established British Computer Society. He explains: “I thought that we should start a regional group and try to bring in the local authority people who were going to try and put computers in, to get their rates in and so on; the various technical people along the Tyne, who were shipbuilders and designers of marine engines and this sort of thing. … We started very small indeed and would try to invite anybody who came to the university who looked as though they might have something useful to say because they’d come in on their own money rather than ours. We hadn’t got any.”

1963 saw organisational changes between the university divisions of Durham and Newcastle and the computing laboratory was transferred to Newcastle. It changed its name from the Durham University Computing Laboratory to the Newcastle University Computing Laboratory. Ewan became a member of staff of the University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

As well as taking on more managerial tasks, Ewan continued to lecture on about two days a week and to be associated with some of the research projects that were going on, rather than actually doing the research work himself. He says: “I had already made that choice when I applied to become Director of the Computing Laboratory. One knew perfectly well that there was going to be a role in helping other people do research, rather than doing it yourself.”

There was some early work on automatic type-setting and word-splitting in order to enable justification of lines (aligning the right edge of text), on information retrieval, also providing a service for the American medical information system MEDLARS , on forming school time-tables, as well as much computing for scientific and engineering applications

Ewan was made Pro-Vice-Chancellor at Newcastle; he was the first Acting Vice Chancellor and then a Vice-Chancellor who was a computer professional. During his tenure he was also responsible for procuring computers and witnessed the development of many of the major innovations in technology from the likes of Xerox, IBM, ICL to General Electric. Newcastle University eventually decided upon IBM as a way to deliver a multiple access computer, as Ewan explains: “The thing that we had done was to seek to have the first multiple access computer, not merely in Britain, but in Europe, when we put in the IBM 360 Model 67, which was the first of the machines which had virtual memory.”

Its installation was a success, Ewan adds: “I was of course absolutely nervous about this, and, I spoke to the then head of IBM, who was Eddie Nixon, also a Cambridge man, and I said, ‘Look, if this were to fail, it would be a dreadful blow to the reputation of IBM.’ It would probably be the end of my career as well, but I didn’t mention that, and he very much rose to the occasion. When the machine came in, we had two first-rate engineers, and they stayed with us for a long time. Eddie Nixon had arranged that when almost anybody in IBM’s research units in the States came over to Britain they would come to Newcastle. We would get them to talk to our software people and that very much put us on the map; anybody who came over from the States, at IBM’s expense, would come via Newcastle. It also tied in with the IBM seminars which started as a result of Ewan’s feedback on one of IBM’s seminars ; he proposed a different format , suggested holding them in places like Rio , Capetown or Newcastle . The company asked if they could be held in Newcastle with advice from Ewan and his team on topics and speakers. Ewan says: “The ambiance that grew up around this support from IBM was very valuable to us in Newcastle.”

While at Newcastle, Ewan wrote three books with Leslie Wilson, based on the university’s courses. These included Information, Representation and Manipulation in a Computer, An Introduction to Computational Combinatorics, and Information Representation and Manipulation Using Pascal.

Ewan moved to Reading in 1979 to take up the position of vice-chancellor. Ewan describes what the role involves: “Even in the days when I was a vice-chancellor, the turnover of the University of Reading was more than £100 million a year. So, although the vice-chancellor is not the chief executive, he is effectively responsible for a multiple-task job. On the one hand you’ve got a business operation to run, and it’s much more of a business now with the fees forming a very large part of the income. But even at that stage, we were the biggest hotelier in the area with all the halls of residence, with a big catering operation of 20,000 meals a day or so. We were the biggest University farmer. There would be one or two other business operations as well. But really, The university was there to do advanced teaching and research. The vice-chancellor is technically responsible for to the management of the university.”

As vice-chancellor, Ewan spent less time on research and computing, however there was one area where he used his insight to ensure security of the university’s financial systems, he explains: “I did take a number of decisions in respect of computing which were Luddite rather than anything else. I was frightened to death that the University of Reading, whose vice-chancellor had been a President of the British Computer Society, would be the first university to have its finances hacked. So, I always insisted that the computers on which the finance was done were totally separate from the main computers of the university, and indeed, in my time, there wasn’t any electronic connection at all.”

Ewan enjoyed his time at Reading immensely and says: “I think it’s one of the best jobs in the world. You are surrounded by extremely bright people, some of them perhaps not quite as bright as you hope they are, or not quite as bright as they think they are, but you are surrounded by very able people indeed, who every now and again will decide that there is something that they wish to achieve, administratively, and they put all their, their abilities into doing that. When they do that, they are formidable adversaries. But it’s so exciting and so interesting and of course, visitors to the university are of a similar calibre. If you are very lucky, and, or perhaps unless you are very unlucky, you will encounter students who are brighter than you are.”

Ewan says that there are numerous things that he is most proud of during his tenure at Reading, including having managed the contraction of the university following the Thatcher cuts in a way that maintained harmony and the activity of the university. Under Ewan, the university also saw an increase in the number of FRSs and fellows of the British Academy, and Ewan was able to save the Department of Archaeology, which now has three FBAs among its staff.

Ewan retired in 1993. He says that despite his interest “You can’t pretend in a subject advancing as quickly as computing science that you are current. You can’t keep current. I couldn’t keep current really for very long after I became a vice-chancellor.” Today, Ewan still attends past presidential lunches of the British Computer Society and the Statistical Dining Club which is associated with the Royal Statistical Society.

Ewan says: “ I think we ought to make a distinction between the use of computers that everybody is going to have to be competent at, or devices which have computing in them. As far as careers in actual information technology itself is concerned, I think that there will still be a flourishing career available to do things that we haven’t really embarked upon yet. Robots and automata have developed in an awful lot of ways already, but there’s going to be many other developments that will require people to be innovative and efficient. I am pretty concerned about computer security, and the blending of communications with computers. In the early days there wasn’t any at all; it was merely forecast, and now of course it’s total and it’s presenting problems. I think those sorts of problems are going to engage very able people for a long while.

The British Computer Society (BCS) is today known as BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT

Ewan believes that despite a slow start, the BCS has been an enormous instrument for good over the years. Ewan was President between 1984-5 and says of the experience:

“It was interesting. But you see, at that stage I was Vice-Chancellor at Reading, and so I really was rather busy, so I’m sure I did much less than the presidents of the British Computer Society have done subsequently. I went around the country a fair amount, but it had to be fitted in with the job that I was being paid to do.”

Past President of BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT

Chevalier, l’Ordre des Palmes Académiques

Honorary Fellow of the American Statistical Society

Northumbria University, Honorary Fellow.

Companion of the British Institute of Management

Hon DSc , University of Reading

Interviewed by: Mark Jones on the 10th May 2019 near Bath

Transcribed by: Susan Hutton

Abstracted by: Lynda Feeley