“I believe in a thorough understanding of every aspect of the business. However that is not enough to succeed. One needs to take some risks with ones career in order to stand out from the many other excellent people around you.”

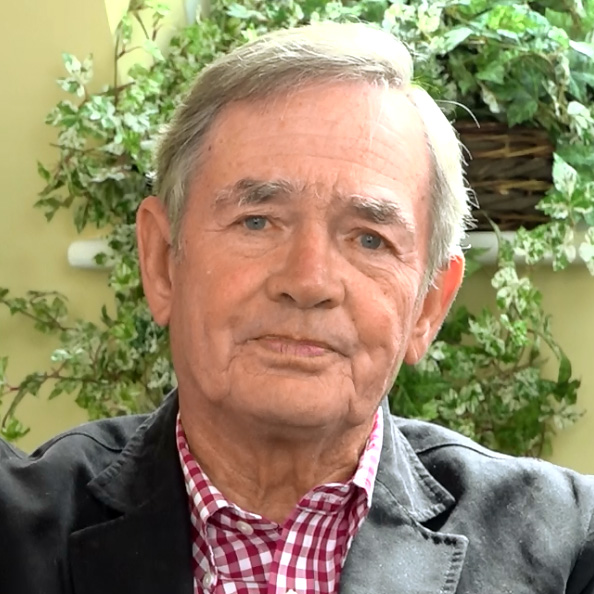

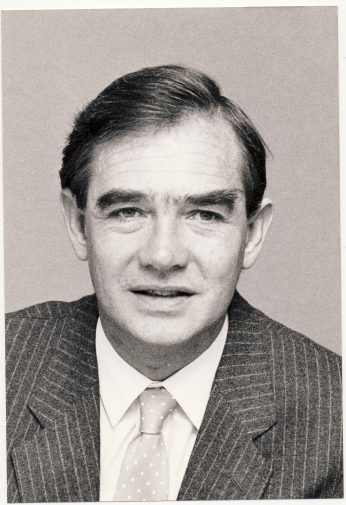

Ninian Eadie was born in 1937 in Wombourne, near Wolverhampton. His father, from Glasgow, was a Civil Engineer who had worked for Robert McAlpine as a chief engineer and between the wars, set up his own business building hospitals, schools and council houses. His mother was a piano teacher who became a physiotherapist. Ninian says that both his parents were extremely hard working and taught him that success was a result of “dogged determination”. He was the youngest of seven children. His eldest brother (with a different mother) was 20 years older than him.

Ninian was educated in a private prep school in Wellington, near Telford, and went on to Winchester – which he describes as like “medieval monastery”. Following school Ninian was called up for National Service in the Navy and afterwards went up to Balliol College, Oxford to read PPE. He did not like the hierarchy of the Navy – as a junior officer, you were hated by the seamen under you and the officers over you, but believed he gained more benefit from Oxford, as a result of two years in the Navy.

LEO 1960 – 1965: When Ninian joined LEO his first job was to teach programming on the first transistor LEO and later to sell it to the retail sector under Doug Comish. LEO stood for Lyons Electronic Office, a subsidiary of the teashop and bun company. Their computer was the first to be used in business. Ninian says that Lyons was a pioneer of Organisation and Method and they believed a computer would help them pursue that development. The company was more interested in the application of computers rather than the manufacture. In the 1960s it was difficult to persuade businesses to use computers.

He moved to South Africa as a sales manager to a joint venture with Rand Mines, a bureau company. The machine, (deletion) LEO III/2, was being used to run the payroll of 130,000 workers from the gold mines. On returning from South Africa, Ninian was asked to do the corporate rebranding for English Electric LEO Marconi Computers, working alongside Wally Olins (later responsible for the corporate branding for Orange).

The Post Office 1965 – 1968: Ninian became consultant for the Post Office, implementing applications such as Telephone Billing, Premium bonds, the Savings Bank, and later the National Giro. He had around 100 programmers at the Post Office working in Intercode for the Giro and Premium Bonds. The Savings Bank application was written in CLEO, a high-level language.

Ninian joined ICL in 1969. ICL was formed from ICT, International Computers and Tabulators, and English Electric Computers following a merger of the two companies. The Government wanted a single UK champion, although Ninian believes the companies were misaligned as ICT was a hardware company and English Electric was a software company. English Electric was a company which was industry-organised and ICT was a company which was geographically organised. In the aftermath of the merger, the two parts of the new company were fighting over the same clients.

Ninian joined ICL in 1969. ICL was formed from ICT, International Computers and Tabulators, and English Electric Computers following a merger of the two companies. The Government wanted a single UK champion, although Ninian believes the companies were misaligned as ICT was a hardware company and English Electric was a software company. English Electric was a company which was industry-organised and ICT was a company which was geographically organised. In the aftermath of the merger, the two parts of the new company were fighting over the same clients.

At the time of the merger Ninian was still working on the Post Office account where he commissioned the new operating system called the LACES Monitor for the Heathrow Customs system. He was then made a Regional Manager responsible for financial institutions throughout the United Kingdom, selling 1900s to insurance companies, banks and stockbrokers. Their main competitor was IBM, as the big financial institutions felt they were safer with the larger company.

In 1971 Ninian returned to marketing, working first of all in Local Government and then as the Marketing Manager for the Government and Public Corporations under Peter Hall. During this time Ninian was also responsible for the UK launch of the 2903 which was a rebranding of an existing small computer which was a “wonderful new machine”. There was an urgent need to build smaller systems to compete with mini-computers now being offered by DEC and others. This led to the high profile job of launch manager for the New Range, and his subsequent appointment as Sector Manager for Government, Defence and Universities. The government was a big customer for ICL as they had a procurement policy of buying from the British company.

The New Range proved to be very unreliable. Ninian believes the reason for this was that the code was inaccurate, and the operating systems were not tested rigorously enough before being put into operation. It took around ten years before the system worked properly and he describes it as a “catastrophe” for ICL; the cause of their eventual downfall. He says the big machines made money, because of the large maintenance contract that came with them paid for by the customer.

In 1981 Robb Wilmot and Sir Christopher Laidlaw joined the organisation, creating a different approach. Ninian took one of the first CAD workstations along to Robb, a small system called a PERQ, telling him that he believed this was the way forward. As a result Robb made Ninian the Director of Product Marketing. He describes himself as Robb Wilmot’s “gopher”, working long hours with no breaks. He says they were all exhausted through hard work but the result was that the company advanced dramatically.

They created the One Per Desk, a machine that “didn’t sell, didn’t make money, but was terribly popular”. Robb wanted to produce a machine that had a telephone, using a gate array from Clive Sinclair. It would work for 30 minutes after being switched on and then it would fail. The operating system was eventually used on Symbian mobile phones and the Psion organiser. Ninian describes Robb Wilmot as having a “scattergun approach”. He says around five per cent of Robb’s ideas bore fruit, and he never followed anything up, but he was able to convince people both inside and outside the company that his ideas were fantastic.

1982 Fujitsu: From 1982 ICL developed an alliance with Fujitsu to enable the production of a second version of the New Range hardware. Fabricating silicon was too expensive for ICL to fund on its own. Through the partnership they produced the Series 39 system which was very successful, and launched a longer-term relationship with Fujitsu.

STC: ICL was acquired by STC which soon had its own financial troubles, as they did not really have the money to buy the company.

1987: Sir Peter Bonfield took over as managing director and Ninian was moved to run International – everything outside Europe. The business was financially successful in South Africa. In Australia the managing director was replaced and the United States was an uphill struggle. Overall they were making good money. The businesses Ninian was responsible for included an off-shore oil company, ADMAR and a PC business manufacturing in Kazakhstan. He spent three week blocks in different parts of the world.

Europe: Following his success running the International operations, Ninian was moved to the equivalent job of President of Europe. At the time he took over, business was challenging; the mainframe business was on the way out. It was a grim four years, until they were approached by Nokia who wanted to sell their PC business. They bought what was effectively the business in Sweden and Finland, the latter accounting for about a third of the Finnish exports. Ninian got rid of ICL’s UK personal computer business and made the Finnish business the PC business. They built a business which at one stage had around 7 per cent of the European market.

1993 -1996 Group Executive Director for Technology: Ninian was given responsibility for all of the technical aspects of the business, covering research, development, manufacturing, and PC distribution.

During his final year before retirement he was responsible for selling off those companies, like those in the Far East, that would clearly never make a profit.

David Caminer and Doug Comish at LEO who taught him to sell

Arthur Humphreys, adored by the customers, a man of few words.

Geoff Cross “didn’t believe in customers”. He understood how to make a profit, “you start off by working out how much revenue you are sure you can achieve, and then you simply cut the costs to leave you with profit”. He introduced profit and loss accounts for every part of the business and cut costs through great attention to detail.

Robb Wilmot who moved him from sales into development.

Ninian considers his biggest success to have been moving ICL into new areas when the company needed to be change. He understood the fast-changing nature of the business. Ninian and Robb Wilmot travelled to Silicon Valley where Ethernet was being made. The chip cost $300 to produce, so Robb spoke to every CEO in Europe to adopt it as a standard, so as to create volume and push the price down. Today, an Ethernet chip costs around $1.

Ninian says the biggest mistake of his career was allowing a corrupt salesman who was taking kickbacks from customers to continue. He should have been fired, but Ninian’s boss told him to keep him on as he was bringing in the most business.

Senior management are always looking for a silver bullet – if everyone did x they would become “infinitely rich and prosperous”. The line manager is getting on with the “sordid job” of selling or making computers and believes that the way to success is through becoming a better salesman or becoming a manufacturer of more reliable equipment. The HR department think that courses and training are the answer. Ninian believes that of the around 20 courses he was sent on in his career, they had added little value. He thinks the key to success is down to the quality and reliability of the product.

Never expand overseas until you’ve saturated your home market.

Interviewed by: Richard Sharpe on the 4th July 2016 at the WCIT Hall

Transcribed by: Susan Hutton

Abstracted by: Annabel Davies