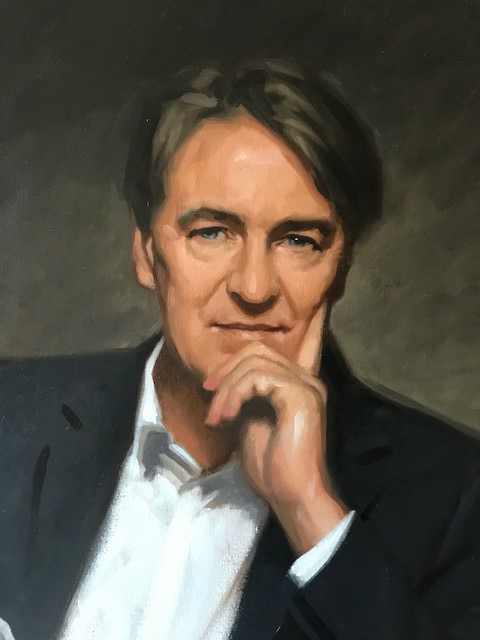

After leaving IBM in 1986 Paul founded Safetynet; then in 1996 Netstore; and in 2001 he founded the Fredericks Foundation, which has become one of the UK’s leading micro finance organisations. In 2005, alongside Paul and Peter Sedgwick, he founded Frank Investments. This business was established to provide long-term investment management services to a partnership of investors. In 2008 Paul was granted the Queen’s Award for Enterprise Promotion. He is a past recipient of the Beacon Award for Creative Giving, and in 2009 received the CNBC/FT European Philanthropist of the Year Award. In 2016 Paul won the UCL Entrepreneurial Inaugural Award.

Paul was born in 1955, in Woolwich Military Hospital in East London. His father was a doctor in the Army, and, was in the UK for a short period, and that’s where Paul was delivered; unlike his brother who was born in Jamaica, or sister who was born in Dublin, The family lived just outside Fleet for the first three years of his life and then moved to Germany for six years. After that they were moved to Cyprus, which he feels was like heaven for a young boy of eight till eleven.

His mother didn’t work: after the war she went to Trinity College Dublin and did a sociology degree, and that’s where she met Paul’s father. His grandparents were all Irish and were on opposite sides of the “divide” and his parents couldn’t be married in Ireland. They flew over to England to get married.

Paul’s secondary schooling was in the UK. He was dispatched from Famagusta in Cyprus to a cold and windy Lancashire coast and a school called Rossall. He thinks it was picked only because it happened to be close to Ireland, and, he could get across to Dublin with some ease on a Liverpool ferry. Because he was at a British forces standard school there was some concern that he wouldn’t pass the common entrance exam. His mother tutored him hard and fortunately he got a scholarship. However, when he got there he realised that he wasn’t really scholarship material.

Paul got nine O Levels and four A Levels at Rossall. His favourite subject was geography and thanks to a ‘great’ geography teacher that was his best A Level grade. He sees it as a classic case of getting on well with a master. The master was a young man, who treated them like adults and gave them his university notes, which meant they were doing much more advanced geography. He also liked history and did well in it at A Level too. He wanted to do economics, because he thought that would help him in his career: he always had clearly in his mind that he wanted to be rich and was going to go into business. His mother’s brother always had very smart cars, which impressed him enormously, and, seemed to be rather wealthier than his family, and that appealed to him. The uncle ran his own business, and Paul thought, that was the way to get things you want. It was as simple as that.

Paul was at Liverpool University, 1973 to ’76 and he absolutely loved it. First, girls were there, which they weren’t at school. He had a sense of freedom and was truly independent. He made two very close friends for life.

One event that shaped Paul during his education was on graduation day. He met the father of a girl from his course who said something which made an impression. “I didn’t start this business till my mid-forties, which was too late. I have a very comfortable life, but, I don’t have the energy level that I had in perhaps the previous decade.’ So, Paul thought, “mm, note to self, must start a business earlier rather than later.”

In 1976 Paul joined Metal Box (a household name at that time) in Reading. He went through the graduate training scheme and had a couple of job offers. He joined Metal Box, as they were closest to a very attractive girl, who he didn’t end up going out with, so, it wasn’t the most professional way of evaluating, and perhaps a small lapse in his drive. Metal Box had a very smart headquarters, and, after doing a couple of months of training, going around the country on expenses, Paul found myself working in a very grimy print factory in Southwark. He got very depressed for the only time in his life, and thought, “Christ, is this it?” So, within three months of landing there he was looking for a new job. He saw something where he could triple his base salary from £2,700 and that was with IBM. So, he applied, very quickly, and, and was fortunate enough to be accepted.

Paul recalls his training at IBM as being the toughest time he has had, because at the end of every week they were tested on what they had learnt. It was very practical stuff; they had to learn a product, they learnt sales techniques, they learnt how to win long-term rather than short-term. It was the best education he had. There started off being 28 people, and he thinks about fifteen of them graduated. They were trained to be salesmen, to sell a range of technology products. At the end of each week when there was a subject, either a product or some academic subject they were concentrating on, if you hadn’t picked it up sufficiently, you were out.

By that stage, Paul had consciously decided to go into a career of information technology for two reasons. One, it was exciting and interesting; two, they paid a lot more than other people. He started off selling golf ball typewriters, photocopiers, audio machines, all at prices which seem extraordinary now. He ended up specialising for a couple of years in selling the word processing system from IBM.

Paul eventually moved on to the minicomputers which weren’t in fact very mini: for instance, the System/38 and System/34 often needed cranes to get them into buildings. However, they’d only have up to 64 terminals, so were quite small in today’s terms. Paul feels he took to sales like a duck to water, and, by working moderately hard, he could get exceptional returns in IBM.

Paul thinks the most important point for a salesperson to remember is, questioning, and then listening to the answers to the questions. He gets upset when he sees bad salesmanship. The skill is understanding the requirements of the customer and then matching your product to those demands. Also, being sincere and open: if it’s not the right product, then don’t sell it to them.

Whilst at IBM almost every January they were being retrained. The IBM training budget was substantial, because, he would say, two to three weeks every year was dedicated to training. His varied training experiences have made him think that there’s a need to make training more practically related, to ensure understanding. He really didn’t grasp accountancy properly until he had to look at his own company balance sheets.

After nine years at IBM Paul decided to go it alone.

In about his eighth year at IBM Paul was looking for business ideas. He teamed up with a chap called Paul Hearson and when they were selling System/38s they were being asked, ‘What’s your disaster recovery plan?’ Which was a pointless question, because there were no disaster recovery companies around that they knew of at the time for those machines. So, they thought there must be a demand for that. They procured a database and sent out a mailshot, “Would you be interested in a disaster recovery service plan?” They got 73 responses out of 600; thought they might be on to something; and decided, “Right, we’re going to have to start a business.” The pair of them resigned in December and started on January 1st. It was quite challenging because they hadn’t raised any money. They just thought they wouldn’t pay themselves. The one glaring hole in their business plan was that they needed to buy at least one computer, and unfortunately, they were about quarter of a million pounds at the time.

Because it was such a large sum of money, they put a business plan to 3i, who were then the biggest venture capitalists or private equity company, around at the time, and they rejected it. So, they went to a computer leasing company called United Leasing and were introduced to the managing director. He put a proposition that they would take an equity stake in the business, own the computer and give them a balloon lease and didn’t have to pay anything in the first year. If they didn’t hit a certain target United Leasing would take the machine back, only losing one year’s depreciation. It was quite a creative way of solving the problem of the computer, but they did have to give up 14% equity. However, they also needed a backup computer, in case they had more than one customer, which, clearly, they were planning to do. They worked with an IBM agent who had a development computer, and that was their backup. The agent got 24 per cent of their equity but, they had to work for them two days a week.

They went six months without a contract, until the first one with Tokai Reinsurance. They thought it was their brilliant and compelling sales pitch that won it but found out years later that it was just that somebody was leaving, and it didn’t make much difference to him, so he gave them a helping hand. By December they had £112,000 in the bank and we had hit the targets that United Computers and Bluebird had asked for.

It took until to the end of their second year to get their first employee but by their third year they had twenty; which was a key milestone. Their business plan was remarkably accurate in terms of costs and, fortunately, they underestimated their revenue so were able to grow the company quite quickly. Their average compound growth rate was about, 30 to 35 per cent. Within five years, they opened an office in Paris, but it took another four years of hard work before it really, started working. In 1993, mainland UK was subject to, terrorist bombings by the IRA and, they were probably SafetyNet’s best recruiting sergeant. The most memorable of those attacks was the bombing which took outside the HSBC building, and they had two clients in that, one was Tokai Bank and the other was Banco di Sicilia.

In the second half of the Nineties, Paul Hearson and Paul Barry-Walsh decided to go their separate ways. They had had nearly eleven great years working together and complemented each other. However, the differences in them began to emerge. There came a point where Paul Hearson wanted to sell the company as he had been approached and offered £12 million. Paul Barry-Walsh was terribly ambitious for Safetynet at the time and didn’t want to sell. It was a difficult time, but they kept it from the company and managed to keep growing for another year or two. In 1998 he decided to buy out Paul Hearson and ended up with a 51% stake in the business. Two years down the road, he reluctantly sold the company on to Guardian IT.

It was in 1999 they received a ridiculous offer of around £120 million for the business, which he flatly rejected because his ambition was to make this a leading British company. However, when eventually an offer came in for £160 million he listened, and they let three or four companies fight out the bid which ended up at £172 million. He feels selling Safetynet was probably one of the saddest days of his life but as he was doing that he was also preparing another business, Netstore, for launching on the main market

Paul was working on his next product, online backup, whilst still at Safetynet. He went out to the States and got friendly with some guys from MIT who had developed an online backup product. He decided, he wasn’t going to share that with Paul Hearson and started another company, called Netstore. In the US it was Netstore Inc, with an American,Ken Israel. The guys in MIT decided they wanted to deal with Paul, rather than their American counterpart, and asked him to act as distributor in Europe. He was very fortunate and within a very short space of time they managed to win Cisco Systems, this provided a worldwide online backup contract, and they had the most advanced online backup service in the world. Once it had done a full backup, it only made the incremental changes: that was revolutionary at the time and cut down bandwidth needs.

Netstore was progressing well and he decided it should be floated on the main market in April 2000. The timing was poor and the appetite for public offerings was declining.

Netstore was at the time described as an application service provider but that didn’t capture the public imagination. It was a form of outsourcing, for mail systems and remote access. So in April 2000 Paul had sold Safetynet and Netstore had gone public. The market was already collapsing owever, and Netstore went public two weeks after Lastminute, who got in by the skin of their teeth. The share price, started dropping almost immediately, and didn’t stop until Christmas falling from 160p to 14 p

The big thing that saved Netstore was, a company called QSP, which was based in Newcastle. It was a mainframe accounting system and Paul picked up on a Friday in Oct 2001 that it was going into receivership in . On the Monday morning he spoke to the receivers and they said, ‘I’m sorry, we’re going to turn it off.’ He replied, ‘I don’t think you realise, you can’t do that, I mean, the Bank of England uses the system, a number of major airlines use the system including BA and SAS, and major power companies use the system.’ It was a big, big mainframe accounting system. He was able to personally guarantee the payroll for a week which provided an opportunity to do some due diligence on the company before coming back with an offer. Paul continued to underwrite the salary payroll, and kept the online operation going. Jon Moulton bought the IPR, and Paul bought the “cloud”contracts. That gave them about, eight or nine million pounds’ worth of revenue, bearing in mind Netstore had less than two million. They then had a base to build from and grew the company from about £ 10 million to £ 50 million in 2009 and from loosing half a million a month in 2001 to an ebitda of £ 6.5 million Netstore was purchased at a pe multiple of 9 to 2e2 a technology consolidator.

Paul has gone back to the continuity services industry because he thinks the service levels are abysmal in that sector now. The largest providers have forgotten the service ethos, He is now Chairman of Fortress Availability Services Ltd, which he feels have got an innovative approach, and he thinks can bring in the sort of service levels Safetynet was famous for.

Paul thinks we are more dependent on technology than ever before, that we’ve got a lot of legacy systems which are ill-protected, and the people who have the right skills are disappearing. There were a lot of vulnerable businesses even before we started seeing cyberattacks. He thinks the, the nature of threats has changed over the years, that business continuity is going to evolve and that a new approach is demanded: that’s what Fortress is going to provide. People don’t care why their system goes down, whether a snow storm, fire, or cyberattack they just need support – no if or buts.

Paul always thought that he’d try and do something useful. His experience of trying to raise funding for SafetyNet made him think, if he couldn’t get funding, what happens if you’ve got no social infrastructure, you don’t know an accountant, or you don’t know a lawyer? What happens if you’re at the bottom of the tree, and you want to start a business? It’s quite hard to get hold of credit when you need it. He thought, “What do I like? I love business”. So, he wanted to encourage small business, and wanted to give those people who didn’t get access to credit a chance. He started Fredericks Foundation, which has a targeted clientele such that if Fredericks doesn’t lend to you, you’re probably not going to get a loan. They relish that, but it’s a very difficult space to be in. Out of 100 applications that come in to them, 93 will be rejected and only seven will go through. All their clients have got terrible credit; but they want them to be completely honest and want to know that they’ve got a plan to sort those issues out. If they have, and if they’ve got a viable business plan, and if Fredericks think they’re the person to execute on that plan, they will back them. If they haven’t, they won’t. So, although they are a charity, they’re quite hard-nosed.

In 2017 they set up a specific fund for women and it’s been successful. Just like in the developing world women are better at paying back than men furthermore supporting women has greater social impact They’ve got lots of quite interesting women’s businesses under way and even if they don’t borrow from Fredericks they can get help with their business plan. They don’t just offer loans, they try to provide a mentor for all the people. It typically takes, from very first enquiry to receiving the money, a couple of months. Even if it’s for £5,000 or £10,000, the process is as rigorous as a £50,000 or £100,00 loan, but. Their average loan for the first sixteen years or so was around £5,000. Now they’re doing slightly bigger loans and the average is about £9,000. Fredericks has invested in over 1600 businesses now and are particularly proud that about 50 per cent of those are still trading after 5 years, which is at least as good as ordinary start ups.

The funding for Fredericks, was initially something that Paul put in with some of his rewards from his other entrepreneurial efforts For the first ten years he put in about, quarter of a million pounds pa, and gave the offices for free, and, also, he asked anyone he invested in to put one per cent of their profits into Fredericks. That’s a major source of funding for them and, because it’s completely unencumbered, they can use it for anything they want. They are expanding quite quickly and expect to get close to three-quarters of a million loans out in 2018, and north of a million loans next year. They’re now changing and providing a service across the UK, whereas, they used to just provide the Home Counties, and a few specialist areas.

Paul is convinced that giving people a loan is much better than giving them a grant. They tried giving people grants, and their attitude to their business was, if it works, fine; if it doesn’t work, well it’s not the end of the world, because they’ve had a grant. But if it’s a loan, they think, “How am I going to pay it back?” He appreciates things can go wrong and, if something happens, they sometimes can’t pay back. Sometimes people get ill, especially when you are dealing with the vulnerable, but Fredericks don’t mind as long as they are told, and if they can validate the illness then that’s fine, and, they write off the loan. If a borrower scarpers or are not in contact, Fredericks are now quite robust and will pursue them vigorously.

In the beginning people wondered, whether we really needed it in this country, when we’ve got the welfare state. The people Paul sees don’t want to be on benefits; they want to be independent, and, they want to have hope – this is a chance to give people hope.

Paul believes strongly that business has to be conducted ethically. Adam Smith argued that the joint stock company severed the link between the investor and the client which would facilitate unethical behaviour, if this is true the Financial Industry transformed to one where “ your word is your bond” in the post war period to one in which the customers were there to be scammed. Which seemed to happen some time after big bang.

At Frank Investments Paul wanted to reintroduce an ethical service where the customer interests was the priority not the employees. They introduced a number of principals:-

- The founders would invest their money alongside their clients

- The owners capital would be treated exactly the same as the clients and they would pay the same fees ( by the way research suggests the investors can get an extra 1.5% pa if the fund manager has his own money in the fund!)

- Fees would be very low

- Capital could be accessed within a week with no penalty

- Money never leaves a client account so they can not be defrauded

- Frank is run for the benefit of the clients NOT the management

Frank invests only in the public market; they don’t do any private investments.

Paul has made over private 30 investments since 2000. Of all the investments he’s made, the first rule is, they should be EIS investments, because that protects you. He ends up investing between £250-£ 500k a year. He admits to being “somewhat hooked on investing.” He really enjoys looking at young companies and helping them, chatting to them. He doesn’t sit on the board, because he finds it boring. But with, all his investments he does try to have a close relationship with the chief executive.

One company that he invested in is called Bluesource; two salesmen that he gave £70,000 to in 2000. The idea they had didn’t work, and they were down to the last £10,000 but now, in their first half year they’ve turned over £11.5M and expect to end the year around £ 25 million They’ve got operation in the States and the UK; they employ about 140 people and they’re doing very well.

In hindsight Paul wouldn’t take Netstore public: he would keep it as a private company and feels that it would have been a successful company if he’d kept it and kept it under his control.

He thinks there are lots of people who could be successful. Some who have been, have had luck on their side. He would define luck as realising opportunities that are presented to you. You’ve got to put your head over the parapet, to receive it. Sitting down saying, ‘I want to be a millionaire,’ is fine, but you’re not going to be a millionaire unless you give yourself the opportunity, and luck is that opportunity being translated into reality.

Paul feels that the IT industry has got used to Moore’s law, but from what he understands, that luxury of ever doubling of power and halving of size is not sustainable. We’re reaching the limits of that. So, ever cheaper technology which has helped us over the last 30 years, is going to come to an end.

He also thinks that AI is going to start taking jobs away in the professions and we’re going to face some big challenges over the coming years, and it’s all being driven by technology. When he was young, technology was just a small part of society. Now technology, is in every part of society, in every aspect. He thinks that if technology gets greedy, and large successful technology companies carry on exploiting the clients they will face an antitrust moment as happened with the robber barons at the end of the 19th century.

If Paul was in technology and embarking on his business career, he thinks he would go and work for a large technology company, simply to understand how commercial technology works. The academic world is not quite the same as the commercial world. He would be looking hard for opportunities to start his own business because he believes working for yourself is so much more rewarding than working for a big company. Even working for a small company is much more rewarding than working for a big company, because your input matters.

Also, he would say, take a long-term view: don’t spend the money, don’t pay yourself much, build up the reserves for a bad time. It’s really important and he sees so many people not doing that.

A lesson Paul learnt during his time at IBM was that IT moves fast. Products come and go, and you must adapt and organise yourself. He thinks it’s important to get the important things right. What’s going to make a difference, what’s a key part of your job, and how will you be judged successful? You won’t be judged on whether you respond to every memo; you will be judged on if you achieve your objectives. So, what’s your objective, what do you have to do, and do that first, laser-like. He feels it’s the same in business. You’ve got to work at what’s going to make your business successful? Have clearly defined objectives and monitor them.

Paul has invested in about 28 different businesses. Many of those haven’t done very well and failed quite quickly. He has been looking to see what’s the difference between the successful and the unsuccessful? Quite interestingly, despite successful, people with great track records and being successful entrepreneurs, some of the ones who have failed are, are exactly those people. He wonders, why would that be? He thinks one, they’re not hungry, and two, the world is changing at an ever-faster rate, and it’s the youngsters who seem to be doing pretty well in his investments, not the oldies. So, now he has a bias in investing towards young people who don’t take out a salary and who have completely committed.

And finally, he would say to entrepreneurs, never risk your house, he did not and if you have that rule you can usually get around the funding problem creatively.

Interviewed by: Jonathan Sinfield at the WCIT on the 2nd May 2018

Transcribed by: Susan Hutton

Abstracted by: Helen Carter