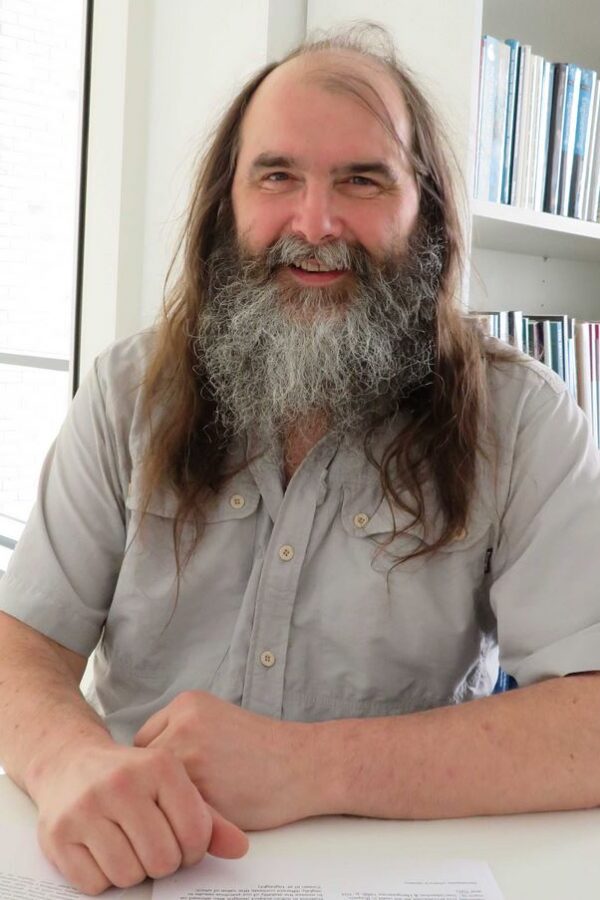

Professor Alan John Dix is Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University and Professorial Fellow at Cardiff Metropolitan University. He is an author, researcher, and university professor, specialising in human–computer interaction (HCI).

He is one of the four co-authors of the university level textbook Human–Computer Interaction. His research interests are eclectic and include HCI, creativity, AI and Data. He is a member of the SIGCHI academy and a fellow of the British Computer Society and a Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales.

Alan Dix was born in 1960, in Cardiff, Wales. His father was a carpenter and Alan says one of his most treasured possessions is a wooden ship his father made out of a scrap piece of wood. His father had been married twice before and was fifty eight when Alan was born. He died when Alan was nine years old. Alan says of him: “I think he had matured over a lifetime so had the wisdom and patience of a grandfather.” Alan’s mother worked during the war for the Ministry of War and then for the Inland Revenue. She later took care of her mother and father and did not meet and marry Alan’s father until later in her life. She gave birth to Alan when she was forty. After the death of her husband, she raised Alan and his older sister on her own. Alan says of her: “From her life, I learnt the importance of giving and doing things for people as much as doing for yourself.”

Alan attended the local nursery and primary schools, and then went to Howardian High School, a comprehensive school in Cardiff. Alan describes himself, saying: “I was probably a bit of a precocious child. … Nowadays they would say I had ADHD. I was always bright and clever, but I struggled. I was not deliberately careless, but I was always very messy with things I did.” Alan enjoyed mathematics at school from a young age and would do maths challenges at home with his mother. At the same time as sitting his O levels, Alan also did a computing CSE which was new at the school. He says of the experience: “We did everything from a thing called CESIL, which was a version of assembly language. We did BASIC as a high-level language. But we also talked about applications in society and the way people use computers, as well as talking about the details of how you programmed them.” Alan went on to study double maths at A level, plus A level computing for which he attended the local FE college. To enhance his studies, Alan used the college library where he preferred the mathematics books aimed at engineers which demonstrated practical applications rather than the pure theory books, and he also watched the Open University. He says: “They covered everything from art, history, the environment, and obviously maths programmes which I particularly liked, and science programmes. It was just glorious.” When it came to choosing a university, Alan, who had visited Trinity College in Cambridge for a weekend outreach programme aimed at comprehensive school students, included the college in his selection list. He says he chose Cambridge over Oxford because he found the exams looked harder which he thought must be a good thing. He adds: “What I didn’t know is, Trinity is the place for mathematics. I did the entrance exams and I not only passed them but got a scholarship based on them.” In 1978, as a result of his scholarship and passing the exams for Trinity, Alan was invited to participate in the 20th International Mathematical Olympiad in Bucharest, Romania. It was his first experience of international travel, he says: “I had spent my life feeling like this alien from Mars, it was so liberating to suddenly discovering there were other alien life forms and be amongst them. That was just such a joy.” Upon his return from the Olympiad, Alan went up to Cambridge and started studying for his degree in mathematics. Part way through his first year, he was fast-tracked into the second year. He puts this down to the work he put in in his school library and through the Open University. However, being fast-tracked only meant that he had completed his degree he would not be awarded it until he had finished his third year, so he elected to study for a postgraduate diploma in mathematical statistics. He says: “I’ve used that statistics a lot since then, and, a year or two back published a Statistics for HCI book, which is less about doing the maths bit, and more about trying to make the mathematics understandable and comprehensible.”

After completing his degree, Alan considered his career options and saw a job advert for a mathematician in the National Institute of Agricultural Engineering, Silsoe. He says: “I went for the interview and there were bright painted tractors and I loved tractors, so I obviously had to go there. I was there for two years, doing maths but also computational modelling of electrostatically-charged hydraulic drop sprays. I was modelling how they behaved on computers which were, at that point, several million times slower than today’s ones. “It was probably my first really intense experience of realising that I do this really intensely computationally precise, but [because of the inevitable simplifications] not correct, view, but what you get from that is an understanding that you can then apply into the real world, what I term qualitative–quantitative reasoning.”

With a first baby on the way, Alan started to look for a job closer to Carlisle where his wife’s family lived. He saw and applied for a role with Cumbria County Council doing COBOL programming.

Alan spent a year doing the role in Cumbria. In 1984, he was introduced to Colin Runciman by his sister-in-law, and Colin invited him to take a position as a Research Assistant on a project funded by the Alvey Programme. The project was called the Five Man Project which saw Alan working alongside Andrew Monk, Nick Hammond, Colin Runciman, Harold Thimbleby, and Michael Harrison. Eliot Miranda was also involved as an RA. The three-year project looked at formal methods and HCI and how to formalise usability principles. While working on this project Alan also completed a PhD in computing. His thesis was Formal Methods and Interactive Systems: Principles and Practice’. He says: “I did my PhD while I was being paid as a researcher. Before that, I didn’t know anything about HCI, but that experience really shifted the course of my career quite dramatically.” After completing his PhD, Alan applied for a gained a two-year Science and Education Research Council, postdoctoral fellowship. He also took part in a three year project under the CSCW programme which included a prototype system that had a chat window and 2D collaborative pinboard.

In 1996, Alan published the first edition of his book on AI. He spent the next few years working across a range of roles, some part-time, others full time, including working as a technical director for a start-up called aQtive, and then on vfridge, which spun out of aQtive. Vfridge was a social network that allowed people to post reminder notes on ‘a virtual fridge’, unfortunately, they realised after a year that it was not going to take off. Alan also worked part-time and full-time with the Universities of Lancaster and Birmingham, plus with a software company called Tallis. In 2008, Alan took a sabbatical and spent that year (and nine more after) living on Tiree, a small island on the west coast of Scotland, where the Tiree Tech Wave was created. He says of the experiences: “It was one of the few times in our life where we feel we’ve really just done something that felt good to do that was less driven by life and more us driving life.”

In 2018, Alan became Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University. He says of the role: “They were looking for a director for the Computational Foundry. The vision of doing really strong computational research that is for the good of people; that’s at the heart of the Foundry vision, and is what brought me to the role. I was also attracted by the way that was embedded into the Welsh context. It was lovely to come back to Wales.”

Asked about the different terms used in HCI, such as: interaction design, user-centred design, user interface design, man machine interface, human-computer interaction, human factors and ergonomics, Alan says: “Human factors and ergonomics existed before the term HCI was coined, and before the concept of being a field, or group of people had arisen for HCI; you can look back as far as Brian Shackel, in 1959. A lot of these were contributing disciplines that came together. HCI, MMI and CHI, as terms were probably all arising almost simultaneously. Crucially, it would never have arisen out of academia at that time within UK. If you’d have said ‘We want to do five areas that we’re going to put money into in computing, what could they be?’, no academic would have said, man-machine interface, or human-computer interaction, or computer-human interaction, but the industry people said this is what we need.” “If I was to distinguish them, I would say that HCI, and MMI, CHI, are the academic discipline. But HCI has always had this mixed identity. There’s a classic paper on whether HCI is an engineering discipline or a craft discipline or science. So there’s always been the study of HCI, and then there’s the design of it and they’re so intermingled, it is hard to tease them apart. My feeling is, it’s moved towards the sense of this is a production discipline, particularly around the dotcom years. So at different points HCI has had this little bit of identity crisis, are we a science, are we engineering? “I have quite a broad view of HCI and it’s about the understanding of computers working with people. The British Computer Society HCI conference’s subtitle is People and Computers, and it has always been, and I think that’s really quite important.” Alan goes on to say that what’s happening in the world affects the growth of HCI. He gives an example of how the growth of computers in the workplace and at home made an impact on interaction design. He continues to look at the impact of the internet, adding: “The difference with the Web is that pushed computers into the domestic market, into the personal market: not just personal as in doing my job, but personal as in, doing my life, and if I’m doing my life, and something isn’t fun, I’m not going to do it. “Satisfaction was always one of the three goals in the ISO standard in terms of making good HCI, but it was always ignored. We know that if people enjoy their jobs, they do better jobs. It’s always been important, but you could afford to ignore it, not put it centre stage. But when it’s somebody in their home deciding whether to use one thing or another, the joy, the pleasure, the desirability, is absolutely key and that’s why experience and then user experience time became important.”

Asked about the outcomes, influences and impacts of the Alvey Programme, Alan says that “probably the most important influences, are human rather than technical. The most significant influence is the way in which people being trained in HCI entered industry.” He also highlights the closer connection between universities and industry as another benefit of the programme in general. He says: “For HCI, the drive came very much from industry, and the way Alvey was set up created lots of either industry collaborations, as well as purely academic ones.” Looking at the impact of the programme, Alan points to the work at Loughborough University. He says: “They were taking the actual methods that were being used by big industry and defence at the time, which have quite long, complex procurement processes and were looking at how does human factors, enter into these processes and where do we place it in this process so that it happens.”

Alan highlights the growth of HCI in the UK across numerous centres including York which he says happened largely because of the Alvey Programme, Loughborough and UCL both of which existed pre-Alvey, QMW, and Glasgow among others. He says: “Loughborough had two strands. They had the human factor strand with Brian Shackel which was oriented toward industry and the SSADM, the big methods that were being used. There was also a strand within computer science, with Jim Alty and Ernest Edmonds, that was concerned with a variety of things including architectures, but also had quite a creative strand to it. Both Edmonds and Jim Alty are technical people. Ernest Edmonds is one of the people who was involved in the Seeheim model, which is the early architectural models for building systems – what’s underneath makes a big difference to what comes to the surface.” He highlights the importance of the cross collaboration with industry and with the growth of networking opportunities through conferences and the BCS HCI group. He says of the BCS group meetings: “As a PhD researcher, this is where you would cut your teeth in presenting to other people, usually in a constructive environment. It was where you learnt about what other people were doing. … So having that national way of people connecting, not just at big international conference, was formative. … It is about learning, seeing the world outside your little group. … It’s the ecology of the HCI community as a whole, which is absolutely crucial.”

Of the future challenges for technology, society and HCI, Alan points to AI and bias as an area of interest that needs addressing. He says: “It’s awareness that at the end there are societal choices, some of which are outside of our hands, but some of which we can at least do things that push in the right direction. What can we do to address some of the potential problems? For example, these issues about bias and that are deeply embedded. Most of the time when people talk about bias, they believe that it is only about human bias that is getting embedded into data and then into algorithms, but there are other kinds where you will create an equally biased and discriminatory algorithm because of the nature of the underlying phenomenon that you’re dealing with. Unless we deal with that, we miss the point.” He also highlights the impact of technology on global economic markets, saying: “Digital technology undermines the assumptions of free market economics, because it creates emergent monopolies. The assumptions of market economics have been broken by digital technology and AI intensifies that. There’s a recent UK government report that says the amount of compute power being used by the large AI models is doubling every three to four months. To put this in context, computational power only doubles in capacity every eighteen months, and prices reflect this somewhat, doubling capacity. That means the ability to be able to produce a given level of outcome, is fast outstripping any but the biggest pockets. So, we have a real societal problem with AI.” Looking towards the positive, Alan says: “However, we could imagine AI addressing some of our societal problems, addressing the disparities of education. If we want AI to serve people, to be working with people, to be working for people, from a technical point of view, we need to understand about it working alongside people.” He concludes: “The bigger challenge is both how we counter some of the massive global distortions and changes in the nature of what global economics is like, which has been changed by AI; and how we can use AI in a productive way? The latter of those is the real challenge point for academics in AI. There are the things that need to be prevented, and they probably aren’t technical things, they’re probably legal and jurisdictional issues. Technology people have to inform those discussions, but they’re not going to change what goes on. What we can do though is address the things that don’t happen naturally in industry. Not trying to do the things that industry wants. This is the opposite of Alvey. Alvey was brilliant in pushing forward the things that industry needed at that time, but now AI in industry is doing all the things that it can do itself. We need to do the things that industry won’t do. It’s about making AI accessible to more people so that it can help you and me as well as large companies. Some of that will happen through the industrial process, we, in academia, should be addressing the gaps. We should be identifying where industry won’t do the good things that should happen, and then, and then doing those things. That’s our challenge.”

Of his proudest achievements, Alan highlights a paper in 1992 which foresaw the problems of gender and ethnic, social bias emerging in black box machine systems. He says: “I remember when I first actually re-read it after many, many years, and, I wondered if I had read things into it that weren’t there, but actually it was the other way round, there was more there than I had imagined. Things that we still need to think about today.”

Asked about advice for others considering their careers, Alan suggests that being able to maintain your long term vision is important. He says: “One thing that I’m aware of that I do in my life is that, I lose track of the long-term vision. I don’t mean the grand world changing things, I mean what is it for your life, what’s important? If you’re interested in everything, and especially if you like helping other people, it’s easy to lose track of that.”

Interviewed by Elisabetta Mori

Transcribed by Susan Hutton

Abstracted by Linda Feeley