Kevin’s advice to a young person considering a STEM career today is to keep an open mind. Kevin recalls when he was at BT and mobile phones were a research project, there were many people who said it was an interesting project but gave many reasons why it would never take off. Also be adaptable to change, don’t stay in one role or one company for too long, the more adaptable you are the more employable you are. This is especially important as AI will make most of the jobs we do today redundant, but it will also create many new jobs as every technical advance has done.

Oh and lastly, have fun in whatever you do in life!

Professor Kevin Warwick was born in Keresley, a suburb of Coventry, England, in 1954. He remembers a happy childhood and after moving several times his parents settled in Ryton-on-Dunsmore, a small village to the south east of the City. Here, Kevin attended the village primary school. Kevin’s father was a primary school teacher and his mother was a housewife. He recalls a quiet upbringing during which he developed an interest in football that later took him as far as playing in the local league in Coventry.

Kevin went to the Lawrence Sheriff Grammar school in Rugby. While at secondary school his parents adopted a little girl named Joanne but at this time Kevin’s father fell seriously ill with agoraphobia, eventually becoming house bound and unable to work. Brain surgery cured his father and Kevin remembers visiting his father in hospital even though he was not supposed to as the surgery was experimental and very dangerous. This event and his maternal grandfather’s Parkinson’s disease sparked an interest in the human brain and influenced Kevin’s later work on artificial intelligence and human/computer interfacing.

While Kevin’s father was off work, there was not much money at home and while he was aware the financial difficulties it did not stop him enjoying his childhood, rather it instilled him with a sense of self-reliance which he retains today.

At school Kevin found mathematics to be enjoyable and easy, he also liked engineering and drawing. Another pivotal moment came when his parents were unable to pay for him to go on a school trip to Germany, he got a part-time job in a Butcher’s shop and saved up, not enough for the school trip but sufficient for his first motorbike, although he could not afford a crash helmet. Tinkering with his motorbike also taught him about practical physics and enabled his interest in the fairer sex.

Kevin left school at sixteen and went into an apprenticeship with the General Post Office (GPO), now British Telecom, where he worked in telephone exchanges. He remembers well the camaraderie of the job and the opportunity to gain a City & Guilds qualification on day release to Coventry Technical College. His time at the GPO taught him a great deal about telecommunications technology and about communicating with people but, while his City & Guilds qualifications were demanding, he realised he would not progress far without a degree.

Having left school at sixteen Kevin didn’t have A-Level qualifications, a pre-requisite for entering university. His natural talent at mathematics would carry him through that subject but he needed to study physics and while he had learned much by tinkering with his motorbike, he needed to deepen his knowledge.

He borrowed a textbook from a library and studied physics during his lunch-breaks and convinced a school in Birmingham to let him join practical classes. Otherwise he was self-taught and eventually passed his A-Levels and got into Aston University.

While still at BT Kevin got married to his first wife. He was just 21 but recalls it was the norm for most people of that era to get married in their early twenties. Kevin and his wife quickly got on the property ladder and bought a semi-detached house in Sheldon, Birmingham. Early married life was focused on establishing a home and his university studies.

Kevin studied Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Aston, which built on his apprenticeship at BT. He chose Aston over Warwick university because the course appealed to him and he was near the top of the class throughout. He graduated with a First and decided to go on a study for a PhD. To challenge himself he chose to study outside of his field of experience in communications and explored computer control systems and the emerging field of microprocessors – a hot topic at the time.

Between finishing his bachelor’s degree and going on to doctoral studies he working for a short period as a children’s playgroup leader in Sparkbrook, Birmingham. Kevin thoroughly enjoyed his brief period working in a playgroup and it taught him a great deal about different cultures, and the problems of inner-city life, as many of the parents were of Asian or West Indian origin.

He planned to return to Aston for his PhD where he would have the opportunity to continue with what he considers to be his forte – research. He had begun conducting research beyond the scope of his undergraduate studies and found that he really enjoyed it.

Kevin secured a research grant from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) but, his supervising professor moved to Swansea university before his PhD commenced. Kevin wasn’t keen to follow him to Swansea and was advised to apply for a research post at Imperial in London.

He was accepted as a postgraduate researcher at Imperial and begun his research into computer control systems. He found the research to be more theoretical than he’d expected and not long after he moved to London his wife became pregnant. This meant his research grant was no longer going to be sufficient and he took on a research assistant role at Imperial.

This move put Kevin back in touch with the practical side of computer control systems and he soon moved on to using techniques such as Artificial Intelligence for simulated neural networks.

Kevin’s next step was to Newcastle University in 1982 where he took a lecturing post. Together with Costas Goutis (now Emeritus Professor at the University of Patras, Greece) he secured a substantial EU grant for development of robotics controlled by artificial intelligence; a project that combined aspects of his undergraduate and post-graduate studies.

It was at Newcastle University where Kevin began to get deeper into the field of Artificial Intelligence, and he came to understand what Alan Turing had said about computers: they can be intelligent but in a different way to humans. He found much of the early writing about AI to be quite limited in its thinking of the ways in which computers could exhibit intelligence, especially where creativity is concerned.

Through his research and practical work in developing AI enabled control systems for robots, Kevin developed a deeper understanding of how computers learn, and that the way they learn and what they learn is different to the way humans learn which in turn raises many ethical questions about the degree of autonomy that can be granted to AI enabled systems.

Kevin moved to Oxford University in 1985 where he was associated with Somerville College, the alma mater of Baroness Thatcher, who he met while at a London fund raising event for the College. Kevin was lodged in the College while relocating his life from Newcastle. He was impressed by the culture of Somerville College and especially the strong women who were associated with it. One such example was the Principal – Baroness Daphne Park, a former MI6 spy and one of the team who worked at Bletchley Park during WWII.

Notwithstanding the fact that Somerville was an all-female College, well at least so far as students were concerned, he remembers one night when the fire alarm went off a remarkable number of men who appeared from the College dormitories during the evacuation of the building only to disappear soon afterward.

It was at Oxford that he first began to connect his research into AI and neural networks with the medical field, especially Parkinson’s disease and on prosthetics. Kevin’s natural curiosity and ability to forge connections between different topics paid off during his mealtime conversations with other academics at Oxford. He wasn’t daunted by the arcane ritual of Oxford and the inevitable hierarchy. He maintained his inquisitive outlook, though he recognized that research at Oxford, as with Cambridge, was and still is exceptionally well funded and in a privileged position.

After a short stint at Warwick University he moved on to Reading University in 1988 where he became a Professor and Head of Department of Cybernetics. He found the department was under resourced and lacking students; one of his first actions was to make the course more interesting to attract more students.

Kevin reached out to technology companies that he knew of in order to collaborate on robotics projects. One example was a remote monitoring system that tracked the movement of people in a building, recording which rooms they went in to, when, and for how long – building up a picture of human behaviour so far as movement was concerned in the work environment. It was also at Reading that he got involved in the first discussion about embedding technology inside a person, augmenting the body with microchips.

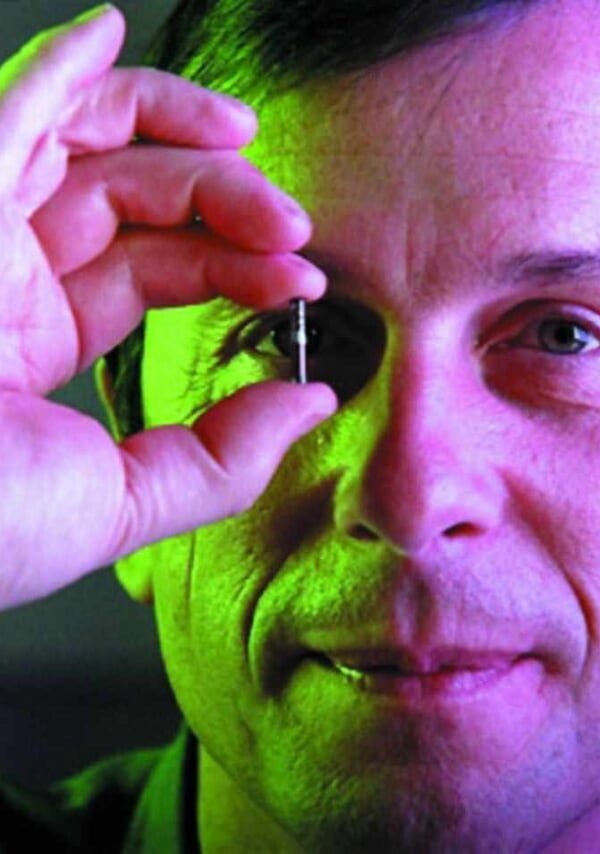

Kevin took the decision to be a guinea-pig for the first microchip (Radio-Frequency ID enabled) implant in a human body, and working with his GP they figured out a way to sterilize the fragile glass casing of the implant capsule which was subsequently implanted into his left arm. This implant, combined with the capability of tracking and monitoring movement around a building allowed the computer to open doors for him, switch on lights and even greet him as he entered the building.

Alongside this ground-breaking project Kevin’s team worked with a young group of musicians, 4 brothers of Elvis Costello, to use an AI enabled computer system to create pop music, although that project didn’t receive anywhere near the publicity that was generated by his implanted RFID tag!

He was surprised by the level of publicity that was achieved, in large part due to the efforts of his sixteen-year-old daughter who had just completed her O Levels. His daughter wrote to many newspapers and other media outlets and it seemed the time was right for this invention as heart-pace makers and hearing implants has recently become accepted, and while there was plenty of science fiction about augmenting the human body with computing technology, Kevin was the first to do it. He attributes the success he achieved to being in the right place, at the right time, with the right idea and of course the right GP who was willing to try it.

The implant was removed just 10 days after it was fitted, and that proved to be the right decision as the casing of the implant was very fragile – one smashed by falling onto the floor from the height of a chair.

It was from this practical research into embedding computer chips into humans that the next step evolved – that of sending computer signals into the human nervous system and vice versa. At the time there were two ways of coupling a microprocessor to the human nervous system, one based on gripping a nerve with a metal ring and another developed in the US called a Utah Array or Microelectrode Array.

Kevin managed to secure a supply of Utah Arrays from the US and persuaded Peter Teddy, a consultant neurosurgeon at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, to embed a Utah Array into Kevin’s nervous system. The size of the packaging for the microelectronics and the Utah Array was too large to embed inside his body at the time, but in 2002, aided by a team of four neurosurgeons, he had a Utah Array connected to the nervous system in his arm with an external package held in a small gauntlet.

This breakthrough led on to research into whether the human sensory system could be enhanced to pick up on a wider spectrum than the human brain is designed to process, for example: UV rays, ultrasonic and ultraviolet. It also raised the question of whether a person with sensory impairment, such as paralysis, could control technology with the aid of embedded micro-electronics connected to their nervous system.

Kevin subsequently went on to trial ultrasonics, enabling his brain to pick up on movement in his environment while blindfolded, much as a bat does. He also controlled a robot hand in Reading University from impulses sent from his nervous system via the Internet while in Columbia University, New York. This experiment allowed him to feel the grip of the robot hand on an object in Reading from the other side of the Atlantic.

With the support of his former research colleague, George Boulos, Kevin’s wife participated in an experiment in 2002 in which Kevin’s and her nervous system was connected to the internet. As Kevin’s wife closed her hand, Kevin could feel the impulse back in the lab – the first electronic human to human nervous system connection.

For Kevin this was a ground-breaking moment as important as Alexander Graham Bell’s first telephone call. So far the technology has only been used in a handful of patients with therapy needs, but has not yet become mainstream. The field remains largely one of research, but also one in which the UK leads.

While Kevin has been more interested and excited by the robotics aspect, he’s still involved with Artificial Intelligence, a topic that raises many ethical questions. Indeed one question is: Are computers intelligent, or are they just learning machines? What if computers do become truly intelligence and autonomous, able to make their own decisions.

Recent developments in AI have enabled a computer to pass the Turing Test, but Kevin believes the test is too narrow and too simplistic to reflect true human intelligence, after all it’s based on only a conversation. Kevin doesn’t think computers have reached the state where they can exhibit a general artificial intelligence across a wide array of capabilities.

NB. AI today is limited to specific functions such as natural language processing or facial recognition. There is no system that combines all AI capabilities in a single, general AI computer.

Kevin is currently focused on how computers can be used to support people suffering from Parkinson’s disease, inspired by his childhood experiences. He’s currently working with Professor Tipu Aziz, a consultant neurosurgeon at the John Radcliffe Hospital, to find ways of overcoming Parkinson’s disease through the use of AI such that a computer can predict and manage muscle tremors before they start. Kevin is also working on research into assisting people who are paralysed by rewiring the nervous system with micro-electronics supported by AI, thereby restoring their neuro-motor capability

For the future Kevin sees great potential and great risks for AI and robotics, on the one hand it has the potential to enhance human consciousness, to allow us to think and sense in new ways beyond the limitations of the human brain, on the down-side the risks of delegating too much control to AI systems are serious and very real, especially as AI becomes and robotics become part of the war-fighting capability of nations. He also sees a future where we can cure diseases such as schizophrenia or even the common headache with the use of embedded micro-electronics – he calls it electronic medicine.

Reflecting on his career he really enjoyed his apprenticeship at BT, it was a great hands-on experience and he still keeps in touch with some of the people from that era. He also recalls with affection many of the scientific experiments, especially the BrainGate with his second wife Irena.

Kevin’s wife is Czech and he visits Prague regularly, teaching at the Czech technical university from time to time, his Czech isn’t brilliant but he enjoys the cultural difference in Prague and still keeps in touch with his youthful interest in football by following the team Viktoria Žižkov.

His advice to a young person considering a STEM career today is to keep an open mind. Kevin recalls when he was at BT and mobile phones were a research project, there were many people who said it was an interesting project but gave many reasons why it would never take off. Also be adaptable to change, don’t stay in one role or one company for too long, the more adaptable you are the more employable you are. This is especially important as AI will make most of the jobs we do today redundant, but it will also create many new jobs as every technical advance has done.

Oh and lastly, have fun in whatever you do in life!

Interviewed by: Tom Abram on the 10th June 2019 in Tilehurst, Berkshire

Transcribed by: Susan Hutton

Abstracted by: Lynda Feeley