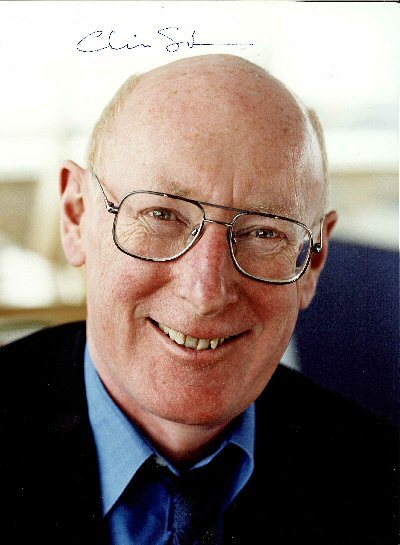

When asked what he would be most known for Sir Clive, in his own succinct way, answered with five words: “transistor radios, calculators and computers”.

Even as a schoolboy Sir Clive Sinclair was scribbling designs for devices in his notebooks. He has a string of “firsts” to his name: the first microcomputer for £100 and the first really pocked-sized calculator are just two.

He was not only an electronics designer but also devised a business model of high-promotion mail-order sales. He brought computing into the home in the early 1980s and created the platform for thousands of computer games. He continues to innovate, working on electric vehicles.

He has natural abilities to innovate, special mental endowments to see where technology is going and to create products; and the capacity to develop successful business models.

Sir Clive Sinclair was interviewed by Richard Sharpe on 28 February 2019 at his home in London.

Clive Sinclair was born in Ealing in 1940. His father was a mechanical engineer and his grandfather was the leading naval architect in Britain, designing battleships. He enjoyed his school days and moved frequently attending 13 schools. He developed his interest in electronics from a very young age, he says: “I remember when I was a schoolboy, at the age of eight, my father bought me a crystal set, which I absolutely loved and was amazed by and I think that triggered off an interest in electronics.” His interest would further develop into building things as small as possible and for the best value possible, leading to the first affordable home computer, the ZX80.

While his parents wanted Clive to go to university, he had other ideas and wanted to get out into the world and make a living. He got a job with Practical Wireless as a journalist and told his parents it was a holiday job. By the end of the “holiday” Clive says: “I was doing well and that was the end of it, university-wise.” It was at Practical Wireless that Clive got to experiment with electronic components and started building things. He stayed in journalism until the age of twenty-three.

Having experimented with electronic kits, Clive started Sinclair Radionics in 1961 designing, building, and selling small radios by mail order, a new business model approach at that time. He says it did not require a great deal of insight: “What you needed was a soldering iron, it came with a printed circuit board and it wasn’t too difficult.”

Following on from radios, Clive, together with his brother Iain, an industrial designer, started designing and developing hi-fi kits with turntables and amplifiers; System 2000 and Neoteric. They were well received and sold well, also by mail order.

In 1972, he made the Sinclair Executive, a slimline calculator costing just £79. He explains: “So called pocket calculators in those days, were closer to the size of a brick than a pocket instrument. My idea, with my colleagues, was that if I could take the chip and reduce its power consumption by switching it on and off, so it was only on for ten per cent of the time, literally ten per cent, I could cut the power consumption dramatically. I had this idea that the chip would retain its data if it was switched off, and it did, by sheer chance, by luck and so I was able to use the power consumption, so instead of having great hefty batteries, had hearing aid cells. It was only eight millimetres thick and it would just slip into your front pocket.” In 1975, Clive designed the first watch with a single chip, which despite some initial technical problems, sold well. It was produced as a kit version.

In 1979 Clive moved into computers. His breakthrough came with the ZX80, followed closely by the ZX81 and ZX Spectrum; the latter two were produced under the company name Sinclair Research.

Clive developed the idea for the first home computer under £100 after he watched the joy his son found playing with the Tandy TRS-80. He explains: “I saw what computers could do, but they were very expensive. The equivalent to perhaps £2,000 in today’s terms, and I thought, having seen what pleasure they could bring and how readily a youngster could program one, if only we could make one for the right price, which I deemed to be £100 in those days, obviously a lot more today, then it would become something that every man could have.”

Clive says: “The ZX80 used a lot of discrete components and then with the ZX81, I mocked up a lot of the discrete gates into one chip from Ferranti; the entire computer only had four chips in it, at a time when the best competition had 46.”

Alongside his brother, Clive worked with designer Rick Dickinson who designed the look for the ZX machines. Clive says: “I have always loved good design. I can’t do it, no skill at all myself, but I can appreciate it, and my brother is a very great designer and I’ve always loved his work, and the work of others.”

In the mid-eighties, the market for computers hit a downturn and Clive shifted his focus to electric vehicles; one of his life passions. In 1985 he produced the Sinclair C5 with he says, “disastrous results, but otherwise quite enjoyable”. He had originally started paper designs for electric cars forty years earlier. This passion today sees him focusing on electric bikes. He adds: “I also did the Zike, an electric bike, and I’m still sort of doing electric bikes. At the moment, they’re not on the market because the European Union has imposed a punitive 130% duty on them, so I can’t import them and I don’t think I can get them made in the UK, though I might try.”

Clive has always been an optimist and taken a tenacious approach to both design and business. He says: “It’s just a natural optimism and I always firmly believe that the future will be good.”

Clive, a member of Mensa and Chairman for seventeen years, while describing Elon Musk as a genius, shies away from the title himself, saying that it is for other people to judge. He attributes his ability to create ideas to being able to project forward saying: “It’s projecting from the present; one can sort of see a trend and follow it through, nothing really more clever than that.”

“I think what I’ve done well, if I may say so, is to see the future. Forty years ago, I gave a talk to Joint Committee of Congress on the future, that was the purpose of the committee. I projected a lot of things then which came to pass, including driverless cars. I remember saying, you enjoy driving, do it while you can because one day you won’t be allowed to. And that was a long time ago.”

Clive famously does not use the internet. He attributes it to a combination of laziness, having never learned to use it, and never having found the need for it. He prefers to read print on paper, books, magazines, newspapers etc rather than getting data from a screen.

His advice for young people entering IT today or on becoming entrepreneurs is, “Don’t give up. Stick at it.” Advice which is a reflection of his own tenacious personality.

Clive believes that the UK has potentially the best engineers in the world, citing the aerospace industry as an example, saying: “We have brilliant engineers in this country, perhaps the best in the world. We’re the second largest aerospace country in the world because we make so many jet engines and wings for aircraft, don’t make so many aircraft.”

Looking at the future of electronics over the next twenty years, and asked if Moore’s Law will continue, Clive says: “Not in semiconductors. That’s come to an end, because it’s hit up against quantum limits. You can’t make the transistors any smaller; smaller than they are, they cease to work.” He continues; “All industries get to that point. The Bessemer process produced huge increase in steel production, but eventually steel ran out of markets and didn’t increase any more, in fact it declined. And the same happens in semiconductors. The industry stagnates and declines. No way around it.”

On the subject of quantum computing, Clive says: “I’m ashamed to say that hard as I’ve tried, I don’t really understand quantum computing. I can’t get my head round quantum mechanics. I mean, read books on it and I sort of fundamentally know what it says, but I can’t say I quite believe it.”

On the subject of artificial intelligence, Clive says: “Once you make a machine, a robot with human capability, and that’s entirely possible, you might lose control and that might make another machine that’s even better, and so on, so it’s a very dangerous path.”

Asked what the Government should do with the IT sector post Brexit, Clive suggests that it should be left alone, saying: “you get government involved you’ve really screwed it up.”

Clive was knighted in 1983

He was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Science degree by the University of Bath in 1983

Clive is a member of MENSA and was Chairman between 1980 and 1997

Interviewed by: Richard Sharpe on the 28th February 2019 in London

Transcribed by: Susan Nicholls

Abstracted by: Lynda Feeley