Introduction by panel chair, John Handby: I have a career in the IT industry running major change programmes for government and then working as IT Director or CIO of various household names before moving onto manage a networking search company and then consultancy work. Over the past eight to ten years my specialist subject has become social implications of AI.

Before I go onto that I was fascinated by some of the history of the internet that people have been talking about today because I do remember in the mid-1990s working part time as a non-executive director of Swiss Re and we were looking at how you sold life insurance on the internet.

And in the city here there was a club with people from Sky and Marks and Spencer’s and a bunch of other household names. And we were huddled together for warmth. The only person who had done anything commercially successful was Jeff Bezos and he was basically distributing DVDs and books and precious little else.

And I can remember we all kind of, it was like an article of faith, we were gathered together in that room on a regular basis but the amount of commercial business being done on the internet was minute. We were saying, yeah, we think this is going to grow. The thing is going to develop but it was still minute.

It was a real act of faith and now you see the high street is dying and everything’s gone online, it’s just been an absolute massive change. And what those of us working in the industry don’t always appreciate is that something happens like that. People were mentioning the Arpa network and the internet does go back to the 1960s and it’s often the case that you have pieces of technology in the background and then they suddenly take off.

John Handby: The Coming AI Tsunami

You will see rather provocatively what I’ve titled my talk. If you look at technologies they sit in the background for years, and internet technology is no exception. And for most of my career AI has been there and now suddenly it’s come of age. I’ve been talking on the subject for about eight to ten years now and got really little traction certainly among politicians and now governments and the media has grown fond of it.

And there is this thing of kind of riding the wave. You know the technology and innovation is all around us and it’s happening very quickly and it’s leading to an arms race. Those companies in California are leading an arms race between them and governments and some of the governments are good guys and some of the governments are not so good guys.

We’re going through this transformational change. I talk about the coming tsunami, something that begins as ripples and has now become major waves and it’s engulfing us all.

When you look at what’s happening with chatbots and all the rest of it you can see the way in which the whole nature of what is happening is changing, it’s suddenly got this traction. It’s happening very quickly. We’ve got quantum computing coming. The Turing test has effectively been passed. Of course, there is good news. You’ve only got a look at healthcare, the way that offices work, the use of algorithms, manufacturing: there are masses of things going on.

I had experience of this when I started in government in the Department of Health as I worked for two pharmaceutical companies along the way running their technology and the implications for health are incredible when you look at what you can do by analysing patient metadata and when you look at what you can do with diagnosis.

Different flavours of AI

When we come to AI though, we have different flavours: there is classical AI and this was typified in the ‘70s and ‘80s with the idea you could replicated the way the human brain worked and you try to develop systems that would do that and also help you understand how the human brain worked. Then in 1990 or so we went into connectionist AI, absorbing mass data and using neural networks. My own view is you can actually argue whether it’s intelligent. It’s certainly artificial. It is absorbing masses of information. We now record more every two hours than we did in whole history of mankind until 2000.

So vast amounts of information are being recorded and therefore able to be accessed by AI systems. So they’re gobbling up this information and they’re putting it back to us. Now whether that’s actually intelligence or not, I’ll leave you to decide.

If you take homo sapiens, what’s the record? Well, a slow starter. But actually, over time, some amazing developments in getting together as communities, artistic creation and all the rest of it. But massive levels of violence, not just historically but continuing. And you, you know, really the record is not a particularly good one. We currently face a world situation which is not a particularly good one. We currently

Singularity

So, is artificial intelligence the future? John von Neumann was the first person who postulated singularity back in the 1950s and now I think we are getting to that point where maybe some of those Hollywood movies were more accurate than we thought.

And you have to argue or think about why that singularity wouldn’t it happen and when it does happen will it have been a great breakthrough for mankind or person kind. Will it be a great leap? Will it mean that we achieve all the things that we thought we might not achieve? Or will it Just embed all the all the bad things about society? If what AI is now doing is absorbing all this human experience, then does it blow it back in terms of what we do to each other?

So not necessarily good news. On that note, I would like to introduce our next panellists, Vassilis Galanos.

Vassilis Galanos: To have done with AI and Internet Summer/Winter Narratives: Can History Cure the Hype? – Read the full Paper Here

Vassilis: Thank you so much for this wonderful introduction. An honour to be here, especially this panel. If you haven’t read Chris’s paper [Chris Reynolds], up next on this panel please read it. They are part of this conference idea of sharing our preprints in advance so I’m always open to feedback.

My name is Vassilis. I have a PhD in science and technology studies from the University of Edinburgh and I’ve been researching and conducting what is known as a historical sociology of artificial intelligence. My background chapter turned into document analysis. So it became an empirical chapter. So that consists of the history and I was also interviewing AI experts, some more historical figures some more recent ones, to compare views about AI then and now

I’ve also been teaching a course called Internet and Society for four years now. So I’ve been reflecting a lot on the history of the internet on the one hand and the history of AI on the other.

And the more you go into these histories, especially the mainstream histories, and I’m all about diversifying the histories of AI and the internet, you see how they were written, how the victorious people have written those histories.

Big names shaping AI metaphors

So the more you delve into this kind of history you see big names shaping the metaphors that we use, the language that we use, and the argument I bring about, and it’s quite interesting that many of the previous speakers have been linguists or interested in literary theory and French language and so on, is that technology history starts with linguistic choices and that reflects the latest work by Thomas Khun that was almost published before he died, so I’m interested in hype and how hype is created.

Now hype is a relatively recent term. It hasn’t been used for example in the ‘60s and the 70s but if you start studying hype, hype has always been there: hyperbole, right?

So the way people convince each other, the way people persuade other people to get research funds, and that’s where Chris’s paper becomes very relevant in terms of convincing people about your own model, and about your own version of history.

And I’m saying that some of these metaphors that we decided to use are quite bad linguistic choices essentially because they distort from technological advancements what an earlier speaker termed as small-scale innovations. Small scale innovations happen at the same time, but how we describe them diverts our attention from them.

So we like our dichotomies, we like the idea of a summer and winter, we like the idea of the analogue and the digital, we like idea of AI as a companion, but we also like the idea of connection and the two of them being distinct. We like natural, artificial, right? But I say history doesn’t really know these differences. And a little theoretical hand to give you, the winter as opposed to the AI effect.

The AI Effect

The AI effect, some of you might have heard of is a full theory about AI history. Every time AI achieves something, it’s not considered to be AI anymore. It’s getting a different conference, a different journal. The history of connectionism is such a history. Essentially, neural networks have been around for long long time. The idea has been there since the ‘50s or even the late 40s, McCulloch and Pitts, but it took off recently.

Now my paper is pretty much a response to this model, it’s a paper I really like because it’s a very short, just three pages but it makes a very compelling metaphor.

He says that every time there is an AI winter there is a human computer interaction summer. So we are getting tired of machines as companions, we want to connect with them. Right, we want to immerse ourselves into virtual realities and so on. We kind of saw that during COVID. In COVID everything was about virtual reality and the new version of the Google Glasses. Covid finishes and then we have AI again. We have AGI again, like from the ‘90s.

A linguistic perspective

But then my argument is that let’s look at this from a linguistic perspective. And let’s look at this through small scale innovations.

And I’m not going through all the details I have here, the paper is there, you can read it. One of the arguments goes back to packet switching and the way time sharing was used for AI research in the 80s.

So much of what became known as the internet was used between AI professionals in order to communicate with each other. So the internet was essentially a by-product to create our artificial intelligence in the strategic computing initiative in DARPA.

You can also look at the work of Lynn Conway, probably the first openly trans person in the history of computing, covering very large system integration and her statements about the role of internet connection and internet and intelligence through time sharing platforms.

In parallel during the 1980s the connection took off with Geoffrey Hinton and his colleagues who were producing some very important and influential papers. And interestingly what we now consider as AI and the connectionist approach, although because Hinton wasn’t offered a postdoc at the University of Edinburgh people didn’t consider his approach to be called AI, he essentially rebranded the term called neuron networks.

Web to 2.0

So it’s a very distinct field and it’s very interesting to me that now he’s considered to be one of the godfathers of AI through the media. So step two, who remembers web 2.0? I’m a web to 2.0 generation and everything on the web was about sharing, bottom up instead of top down. And that was all about the IT information revolution, information superhighways, we’re going to build up the web and so on.

If you read the initial scientific papers that led to contemporary deep machine learning they don’t refer to AI at all. They cite some of the classics, some of the Minsky’s, some of the Hinton’s, but they don’t cite artificial intelligence as a term.

They do cite web 2.0. So for them it was web 2.0 that brought about this kind of revolution. It was a pretty big data revolution. So, with big data then we have this enabling of Hinton’s algorithms and verbos in the ‘80s that were called hedonistic algorithms because they were based on hedonism, the sort of Epicurean sort of pleasure kind of approach.

And the third step, contemporary AI, where I think from AI we go back to the, I guess, properties of the internet. I was surprised to see that within the first couple of months of ChatGPT’s launching, it was initially used for web searches.

So people were disillusioned by Google’s advertisement-led approach because, at least for now, ChatGPT seems to be advertisement free and seems to carry on this sort of objectivist kind of knowledge that seems to be very balanced or as Elon Musk called it woke, I don’t agree with the term, so it seems that people are using it as sort of authoritative one hit search engine. Which takes us back to that question about what is the internet for? what is AI for? Is it about memory, is it about search, is it about whose memory, is it about power, is it about politics and so on.

Eggpoonntations

And I have I have coined the term in the paper, I call it eggpoonntations. It essentially treats small scale innovations as an egg and spoon race. So you’re there carrying the spoon with the egg and you’re surrounded by images of hype, of linguistic choices that try to divert your attention. But you’re there, you fight for your own research funds, your own research grounds, you want to find a job for you, for your children, you want to build your reputation, your career, and you keep going.

So this tension between hype and history is something that can be useful in the future and that feeds into scientific motivation and things that Chris will talk to you about now. So thank you very much.

Chris Reynolds: Did the Hype Associated with Early AI Research Lead to Alternative Routes Towards Intelligent Interactive Computer Systems Being Overlooked? Paper 1 – Paper 2

Artificial Intelligence research has involved chasing one heavily funded and overhung paradigm after another. The study of commercially unsuccessful projects can tell you not about the economic and political environments, but which projects should get funded and which should be abandoned.

Now what I’m talking about is a project which I got involved with [designing interactive language called CODIL] and which got abandoned. With my background, as a long-retired project leader, looking through the archive of this project I can see it simply doesn’t correspond to the fashionable paradigm.

I was effectively told that when getting publicity, I should produce a working demonstration and an educational package on the BBC Micro.

And I got rave reviews: New Scientist, Psychology Today and in prime educational supplements and I pinned them on the noticeboard.

But I was told: ‘Take them down, you are bringing the department into disrepute. AI is all about getting grants for big, big, big computers’.

At the time I was dealing with the problem of a family suicide and decided I would take early retirement rather than have a complete mental breakdown. And that was why the project ended.

To say a bit more, myself, I’m neurodiverse, autism when I was at school although it was diagnosed in those days and I recently discovered I have aphantasia, which means I can’t recall visual images. Which means that when they were saying AI is all about pattern recognition and reading text, it passed completely over me.

Complex Systems

I did, however, get involved in complex systems. The first one was for a PhD studying chemistry with some pretty horrific maths and one of the real problems was the theoreticians didn’t understand experimental chemistry and the experimental chemists didn’t understand theoretical chemistry. And they all liked to quote each other and show how clever they were.

That got me interested in scientific information and in 1962 I started as a graduate level clerk handling mail (reading research and development correspondence) in an international organisation. In effect I was acting as a human chatbot.

I was archiving, answering questions and writing reports on the mail that was coming in. And I thought that computers might help. I knew nothing about them but I came across the work of Vannevar Bush who in 1946 wrote an article As We May Think and I decided to explore how computers could help. I was also interested in the money as I wasn’t getting paid very well. I then moved to what I now know was one of the most complex sales accounting systems anywhere in the UK in the mid-1960s on LEO III.

I suggested that the opaque, very complicated invoicing system for a million ever-changing sales contracts could be reformatted in a sales-friendly transparent form when terminals became available. And I suggested we design a computer that could do but wasn’t taken seriously.

However, this stage in my career I was headhunted to work on the future requirements for the next generation of large commercial computers which would have terminals and hopefully integrated management information systems by a member of the LEO team who knew a lot about why the Shell and BP systems wouldn’t work.

Proposal for an experimental human-friendly electronic clerk

This research resulted in a proposal for an experimental human-friendly electronic clerk using an interactive language called CODIL (Context Dependent Information Language). It would handle a wide range of commercial, data-based and orientated tasks.

The main requirement was that the system should be self-documenting and 100% transparent and could work symbiotically with human staff.

And maybe because I was neurodiverse I didn’t think I was proposing anything unusual, it seemed obvious to me at the time. It was funded by David Caminer and John Pinkerton. And work started in writing the computer simulation to show that the thing worked and it did work to the level of the original proposals.

However, there was a problem. ICL was born, and if any of you know anything about ICL, Caminer and Pinkerton got pushed to one side in the process and I was in one of the research divisions that was closed down.

However, I was given the permission to take the research elsewhere. I still haven’t realised why what I was doing was novel. What I urgently needed to do was get away from technology and move into what is called the human fields. And I chose in 1971 to go to Brunel University, which had just stopped being a technical college. I had no experience of unconventional research and which was not dedicated to selling the standard technology.

Not corresponding to conventional AI

And the research continued and got very favourable reviews, but I was told by a new head of department that it didn’t correspond to conventional AI, so it must be wrong. And that’s when I left at the time of a family suicide.

Why I’m here is because a few years ago my son said when you go I’ll have to get a skip for all that paperwork which takes up a whole side of the garage and includes program listings, correspondence etc etc and the report which led to the research being closed down by ICL.

And I thought rather than throw it in a skip, I would get back into AI and see where it fitted in. And basically what I did was to discover a packet which I had suggested for invoicing and later moved on was an unusual type of language.

If you take Cobol as a language it maps the task into a digital array. What my system did, and I’d never heard of neuro networks in those days, was map the data and the rules into one language, which was mapped onto an array. And if you said to the array here are the active nodes, the answer fell out. It may seem rather simple and that’s the problem, it sounds too simple. I don’t think anybody had looked at something so simple but it did work.

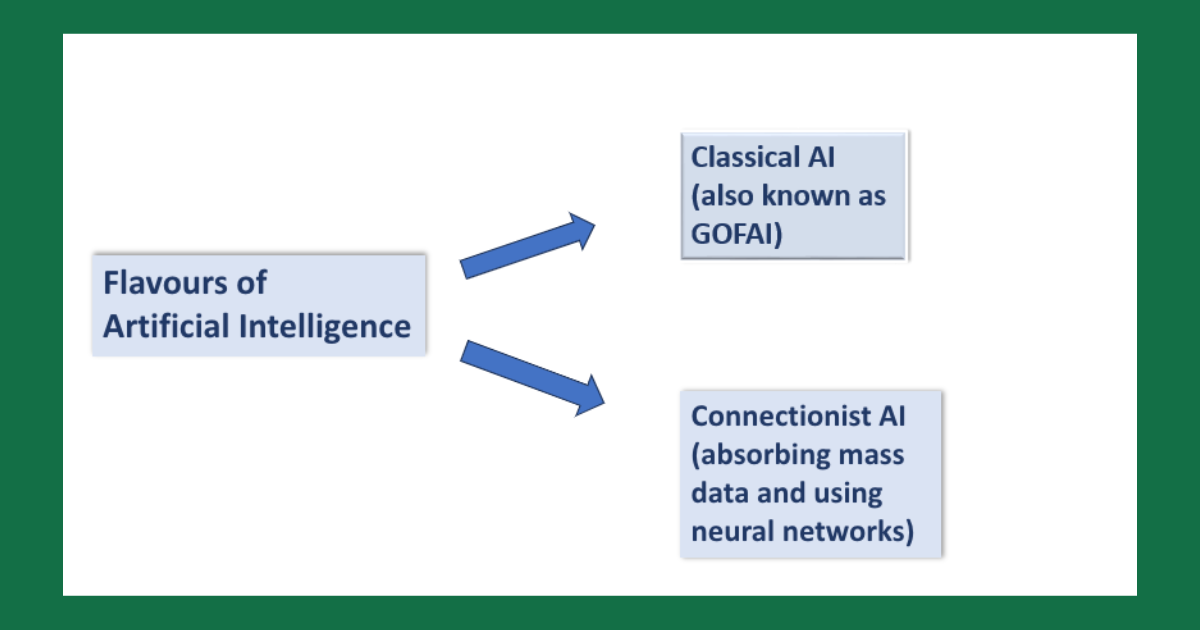

Turing Test and the Black Box

Subsequently I have been looking at standard AI against my intelligent clerk model and the Turing Test. It’s a lovely test and it sets up a black box and if you build a system to meet the Turing Test, you end up building a black box. That is the target. Now if I started off thinking I’ve got a company in a very complex area, everything always changing, then what I’d want is a transparent system.

And I started off by saying I don’t give a damn about the rules, whatever it does it must do transparently, I must always be able to explain.

If you wanted the CPU to address things associatively, you can make a friendly computer. Because the symbolic assembly language of the computer can be mapped in a similar way that humans think.

So, in my recent re-examining of the CODIL project archive in the light of modern AI research, I have found the result suggests that the CODIL approach unconsciously involved (perhaps because I am neurodiverse) reverse engineering the way the human short term memory works.

A key feature was that the language involved describing the task in term of sets, where each set was a node in an associatively addressed network. The system I created said the most important thing is that a human must be able to understand what the system does. I hadn’t read the appropriate psychology papers at the time, so when I set up testing, I said ‘nobody can handle 32 variables in their head simultaneously, But when I started testing I found that with everything you did you didn’t need to have active. Active is the critical word, more than above ten variables and usually less in human short-term memory.

This is radically different to normal programming where the task is split the task into rules and data, which are mapped onto a digitally addressed array of numbers. The underlying story is that the project archives show that there is a possibility that modern AI is going up a blind alley by neglecting brain modelling. The archive also contains much information relating to the lack of adequate support for creative blue-sky research in a rapidly developing field where there is a ferocious rat race to get funding.

I am now writing up a theoretical paper and I’m also looking at how this information should be archived

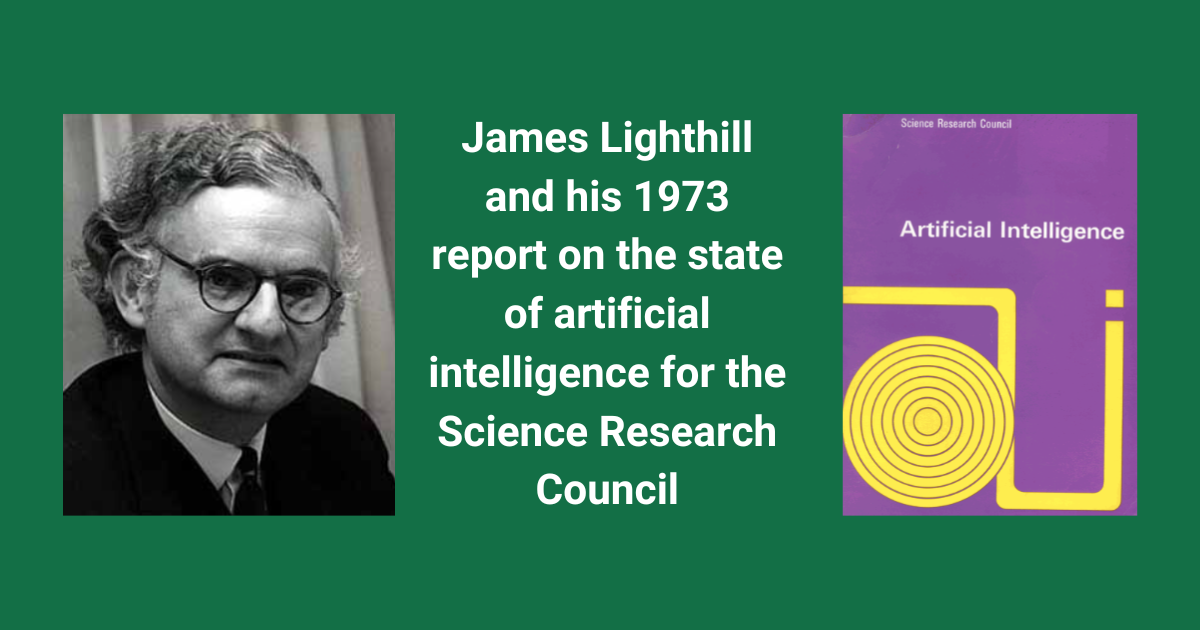

Jon Agar – Why Did James Lighthill Attack AI?

I originally trained as a mathematician then I became a historian of modern science and technology.

The full argument I make can be found in a paper published in the British Journal for the History of Science. It concerns the history of AI and it concerns a particular incident and going back to what we heard from Vassilis about one of the causes of the so-called AI winter, the first real crash in funding in the early 1970s, which had many causes many factors.

One of the causes is often attributed to the mathematician, James Lighthill, who wrote a report for the British Science Research Council on artificial intelligence, on the state of research and whether or not we should be done with it.

Cuts to funding

And basically his critical comments set off a wave of cuts in funding in AI research around the world.

And I’ve always been interested in this moment partly because I’m interested in Lighthill and I knew he had a background in fluid mechanics, generic mathematics that I was interested in and it’s a little archive story.

I’ve wondered for ages about where are Lighthill’s archives. It’s such an important moment in history of computing, Lighthill is such an interesting figure and his archives must be somewhere.

For some reason I could never find them. I’m based at UCL and I finally did another search and it turns out that they were 100 meters away in the UCL archives where he was provost at some stage [1979-89].

Lighthill’s Motivations

In the paper I tell the story of going into the archives and uncovering what I think are some of the motivations behind what Lighthill is doing. It’s usually taken to be an attack on artificial intelligence right and I found two findings.

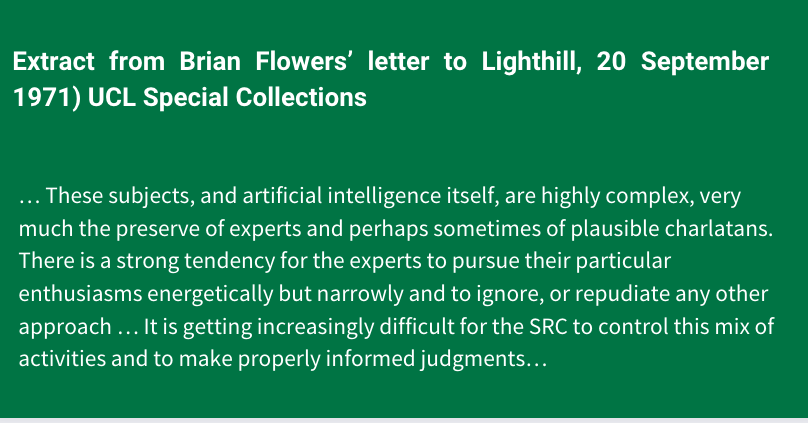

One is to do with where this report came from and it’s an invitation from Brian Flowers who was chair of the Science Research Council in the early 1970s.

This letter [sent from Flowers to Lighthill in 1971] is remarkable, it’s an incredible steer to Lighthill and he says: “These subjects, and artificial intelligence itself are highly complex, very much the preserve of experts and perhaps sometimes plausible charlatans.” The invitation is to do this report but go in there and be a bit critical.

Lighthill is not someone who gets told what to do though, he is very much his own man. So, he travels the country interviewing people getting a sense of where the field is. Not talking to enough people and not long enough according to critics when the report comes out, but that is how he builds up this research.

And when it comes out, it comes out a really curious way eventually published alongside responses from people that he’s actually criticising in the report.

Lighthill’s three areas of AI

Lighthill’s argument is that you can see artificial intelligence in the 1970s as being essentially three areas, at one end you have A, things to do with advanced automation – replacing people with machines.

At the other end, C, we see what you’d call computer based central nervous system research closely connected with brains, psychology and neural networks?

And in the middle, B, there’s this is bridging category, building robots. And this is where you find a lot of that much more general AI work going on. And he basically says that A and C are coherent and advancing fast, but that B is over promising, it has failed again and again and basically funding should be cut severing AI as a coherent thing. He didn’t think AI was a coherent programme. And that’s where the conclusion that AI funding should be cut.

However, this is my argument, when you look at Lighthill’s career, when you look at the specific reasons why he attacks this middle section in particular, it boils down to the fact that what he’s most concerned with is not really artificial intelligence.

Good science and good applied mathematics

It was about what good science and good applied mathematics should be. And throughout his career, and there are quite a few examples of this, Lighthill is absolutely convinced that the best science, the best applied mathematics came from a really close connection with applications and the problems of the world.

So if it wasn’t closely connecting problems being genuinely encountered in the world of work, then it wasn’t going to lead to good applied mathematics or even a good science more generally.

He thought A and C certainly did and B didn’t. So, in general robots could do all kinds of tasks but is just not close enough to specific applications, he thought, to be something that’s going to generate good science.

To conclude, it’s an argument that what we think Lighthill was complaining about, artificial intelligence, is him actually trying to enforce principles of where he thought good, productive science came from. So, we slightly get him wrong, I think.

John Handby: Thank you, some fascinating insights there, if the panel could return, we’ll get some questions from the audience.

Panel disicussion and questions

Mike Short: A question to Vassilis. You didn’t really refer to the language of security and how that changes over time. You perhaps didn’t refer to some of the areas that are now being described as the metaverse. How would those two subjects fit in with your frameworks?

Vassilis: So, the metaverse feeds into the aspect about human computer interaction and virtual reality. And something I spoke earlier regarding blockchain and digital object identification.

Security I haven’t really looked at to be honest but I think it’s an important factor that shapes, these linguistic choices.

Obviously the term itself is used in order to express different things. So, customer security, national security. There’s a vast space between them and one sometimes justifies the other.

Speaking of Jon’s talk, this idea that technology has to be applied, if it’s science it feeds into that security and is used as an applicable source. And partly in response, I think Lighthill comes straight after 1969 and Manfield Amendment in the United States post-Vietnam War were likewise in the States all technology, all DARPA funding had to be applied in terms of security.

Jonathan Aylen in the audience: Can I raise the black box problem? Chris, you alluded to the fact that it’s sometimes very hard to know what’s going on in conventional programmes. I think John went even further and alluded to the existence of charlatans. One personal difficulty I have when using neural networks in a commercial context about 10 or 15 years ago, is that we didn’t have a clue what was going on. This deep concern that because AI is somehow remote, somehow black box, somehow you can’t decompose it into its mathematical equations, somehow it’s almost assuming a life of its own, which you can’t interpret.

How do people feel about AI as a black box?

Chris: Basically, as far as I was concerned there were always black box areas. I was responsible for a time with correspondence with South Africa, with Australia and such like and I have no first-hand experience of farming in any of those areas.

And I think this is an important thing because quite often with black boxes and what’s inside, there’s always going to be something you don’t know.

The important thing I think with humans and the way they handle it is they can handle things they know and they are prepared for things that they don’t know.

And I think this is one of the problems with the connectionist approach.

The system I’ve got you can look at it in that way but I’m quite sure that human brain does not use advanced mathematical statistics to work out the connections.

And I think this is part of the reason why these new AI are black boxes because they use mathematical techniques, which maybe very, very valuable for some tasks, don’t get me wrong, the modern AI and big data is very, very powerful.

I’m using one of the chatbots at the moment in terms of the research I’m doing. It comes back with ideas that I may not necessarily agree with but what it does tell me is what kind of opposition I’m against with my idea and that is very important if you’re trying to be creative.

Question from a man in the audience (James? 2.54.320): A comment for Jon about the Lighthill report, which I’ve managed to have a look that myself. I think one of the analysis at the time was that his views were shaped by the extreme political differences among the various protagonists in AI.

The question I wanted to ask though is about the [why he had such views on] building robots, which is somewhat ironic given that robots today are probably one of the major developments in industrial automation and have transformed the world?

Jon: Yeah, absolutely. And it doesn’t even make a lot of sense calling it building robots in the context of how Lighthill then goes on to describe that category, actually quite a mixed bag of quite a few areas of research and activities. It maybe that it one of the main targets was Edinburgh where some of the main robot work was going on.

Man in the audience (James?): And he used very colourful language too, I remember, ‘pseudo maternal drive’.

Jon: Oh yes, yes, yes, yes, where he speculates what might be driving interest in general intelligence. And one of them is about supposedly men being jealous of the possibility of giving birth.

James, I’m delighted you’re here because your work was really important and I think in that paper you also say that perhaps Lighthill was motivated by either that sort of humanistic dislike or scepticism or concern or anxiety about artificial life and artificial intelligence.

That could be part of a cultural response but I don’t think it works for Lighthill himself. I think you can pin him down throughout his career from when he was at Farnborough to when he sets up the Institute for Mathematics and its Applications and throughout his career to good science and good mathematics.