Martin Campbell-Kelly: I enjoyed the last session and have found this a particularly fascinating conference so far. My title is Emeritus Professor of Computer Science at Warwick University, which would be an offence normally under the trade descriptions act. How I got there was I completed a doctorate in 1980 on the history of computing. And Warwick in those halcyon days decided to appoint me on the grounds that I might be an interesting person to have around. I don’t think many appointments are made on that basis today.

About 20 years ago I wrote a paper called The Internet: Missing Narratives. And it was the fact that in the early 2000s, with the web exploding, that there was a general view that nothing had preceded it and the internet had come from nowhere.

I became very interested in the fact that there was a lot of stuff before then and it’s been fascinating to hear it today. Anyway here’s our first speaker, Brian.

Brian Vagts: Telenet and the Construction of Network Security Culture

The interesting thing about Telenet is back home where I am from, which is the suburbs of DC, Northern Virginia and actually where Telenet was based, is that no one knows about it and I have to explain what Telenet was most of the time, however, it’s already come up twice today. So I feel a little bit redundant and very happy at the same time.

And so, a little bit about myself. I am an associate professor of history at Northern Virginia community college. So we’re a community college, we’re mostly education focused, research focused and periodically we get to break out and go to conferences. I’m also part of the STS programme [Science, Technology and Society program] at Virginia Tech where I’m studying the history of technology and that’s where my paper grows out of.

My training is as a historian. But I graduated in 1996 with a degree in philosophy and for some reason there weren’t that many philosophy jobs available in 1996 but there were tonnes of IT jobs.

In Northern Virginia in a heartbeat you could get a job in IT and so I worked for a number of years, not as a particularly competent IT practitioner, but an enthusiastic one before I ran away screaming and went to grad school and studied history.

And so, I was kind of on the ground floor in Northern Virginia and it had the conceit for a little bit that it was going to be the internet capital and that Silicon Valley would have the hardware, but we have the communications. And you still run across a gross oversimplification that Northern Virginia still has far more than its fair share of internet traffic passing through it.

Data networks

And so, what I wanted to look into is how did people learn to behave on data networks?

It didn’t come from nowhere and the internet didn’t come from nowhere. This is learned behaviour. And oftentimes today there is of course a lot of people, you know, beating their heads saying, how is social media so toxic. Well, we have decades of work going on here.

But where did this come from? I didn’t intend initially to start looking into security.

The problem is, on a documentary basis, I have not yet tracked down where the archives of Telenet are and there’s been enough corporate mergers that it could be in a number of different places.

I have tracked down some people who worked at Telenet, but I’m still tracking down the archives. So I’m dependent on what is available publicly and of course that means what got or gets people’s attention publicly is going to be the security issues.

We had an interesting nexus in 1983, so a little more than 40 years ago now, where we had a mass media event in the form of the movie War Games, which unleashed Matthew Broderick upon the world, which we’re very sorry about.

Hacking incidents

But also a series of hacking incidents, one of which utilised Telenet as a vehicle for attack making it a transport mechanism that wasn’t directly involved. But later there were attacks on the Telemail email service itself. So Telenet was both a vehicle for and a victim of the attack itself.

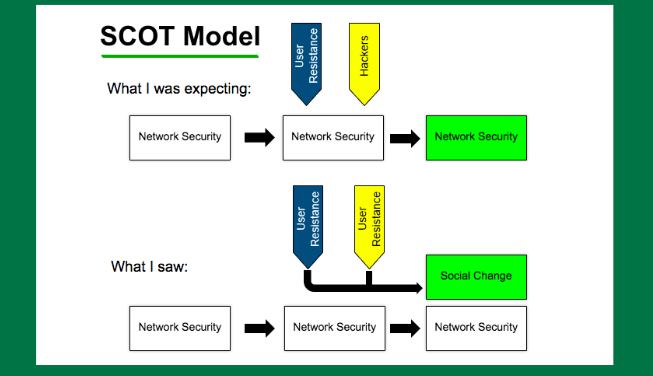

And looking into this idea of the social construction, and I’m using a comment kind of outdated a very simple theory but I like it because I like my theories simple, called Scot (social construction of technology). Basically there’s a feedback cycle. You have a technology and people respond and the technology incorporates that feedback and so I wanted to see how security technology was incorporating this feedback.

The hacking incidents in 1983 are pretty much your stereotypical teenage male suburban hackers, it was a real nice early point to address security issues before the stakes went bad.

And we didn’t address it. So the question is, what was going on with this?

Telenet background

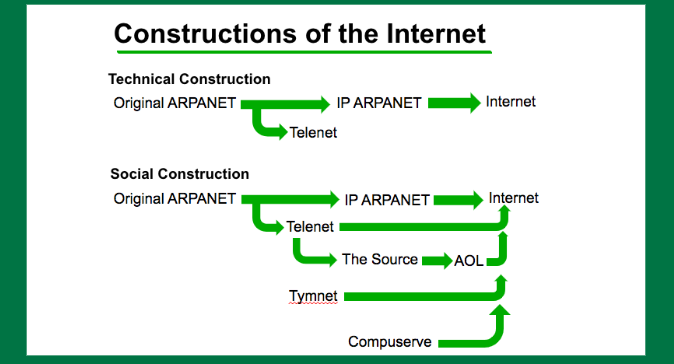

So just a little bit of background on Telenet. Again, I’m arguing against, I don’t think I have to tell you people about this, the Arpanet being the beginning. Arpanet is important but it is largely developing IP. People don’t care about protocols. They care about what they’re doing on their networks. And as best I can tell, in 1983, Telenet is orders of magnitude larger than Arpanet was at the time period.

Arpanet had up 113 nodes. Telenet had more than 2,000 customers. It’s an apple to oranges comparison but each of those represents a large enterprise computer system. And I don’t know how to break that down into absolute numbers of users but several orders of magnitude larger.

And it’s going to be these users that then go on and start bringing, and in addition to Tymnet and CompuServe and the other services of the time of the DBS [deep brain stimulation] world, those learned behaviours into the internet when it starts expanding in 1990s.

So what I’m arguing against in terms of the technical construction is okay, yeah, Arpanet is important in terms of the IP conversion and the development of those protocols. But the social basis is much more bifurcated.

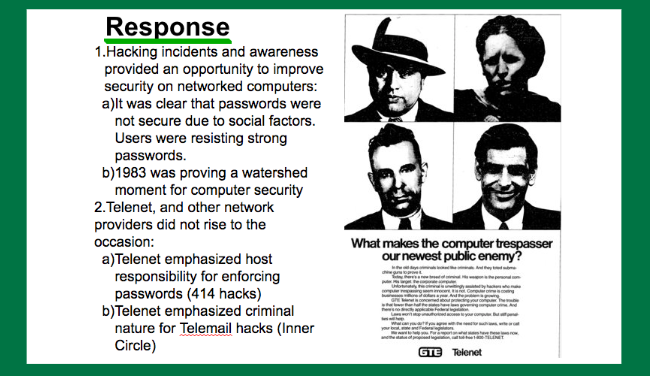

So, how did we respond to these hacking incidents? How did the technology change? And at first what was really disappointed was there’s no changes and in fact it’s almost like a broken record. What led to all of these systems being penetrated was the fact that the passwords were horrible. And we saw, if you watch the movie War Games, the protagonist breaks into the school computer because the password was pencil.

On the Telenet systems it was documented the passwords were the person’s first name and if you’re an administrator you had a capital A afterwards. Okay, so the hackers went after that. You can take this story and repeat it for decades and decades. The security didn’t develop to incorporate this feedback. And I’m like, oh, what the heck I’m on here, so that’s not how it works.

And there were some mechanisms, they were cumbersome, but there were some mechanisms at the time period such as callback modems and a couple of years later the RSA secure ID tokens came out and they had a very slow uptake.

Telenet response to hacking

But we don’t see an effective response to this. And a year after that we get the TRW Hacks of credit card information. So it’s very rapidly escalating in costs. And how Telenet responded to this was interesting.

When you go through the literature of the time period. Most people thought that hacking was wrong, but they weren’t quite sure why. The US code at the time was ambiguous on whether it was legal or not. It had strong wiretapping protections. You can’t mess up data when it’s being transmitted, but if it’s in storage on the computer, well what are you going to do with that?

There is a conflation between software piracy and what these kids were doing and these kids were basically just messing around but they weren’t tyrants as far as I can tell. And some people were like, well, they’re not pirating commercial software, so there’s no crime here.

And what Telenet ultimately did was launch a campaign trying to associate hacking with criminal activity. And they’re playing kind of a two-pronged approach. They’re like, oh yeah, these kids are just organised dupes, but there’s a reference that comes up repeatedly and repeatedly and repeatedly that this is a front for organised crime, for the mafia, which is far from helpful time period is it not?

But later, it’s almost prescient. And so we see in response to this, there’s not much of a change in the technology. This is what I was expecting. But if you incorporate the feedback then there would have been a change in these systems.

Unauthorised computer access

That’s not actually what happened. What we saw in fact was this was altered in social change, this is going on but it’s not the whole process, and we start defining this idea of unauthorised computer access as a new form of criminal activity in and of its own right.

And in doing so, we, kick the can down the road for decades and I’d say we only really effectively started addressing this five years ago, maybe. That passwords should be awesome but in reality, they seldom are. And that in essence we refuse to deal with that technological feedback from this early time period.

And what ultimately see is what is driving this is that cost and ease of use trumps everything else. No one likes the idea of bad security but it’s never enough to overcome those other factors. Ultimately security was and I would argue still is probably a secondary element and that has messed with us long-term.

The paper is on early access on IEEE history of computing and I’ll make it available when it gets published.

Mennatullah Hendawy: IoT Co-production for Inclusive Smart Cities

Hello everyone, I’m joining you from Cairo. I’m affiliated to Ain Shams University as an assistant professor and also to the Center for Advanced Internet Studies in Germany. I’m going to be speaking about IoT co production for inclusive smart cities.

I would say the research is in its initial stages but I’m planning to investigate how citizens, as I’m going to argue later, will become data in smart cities with the use of IoT.

A brief background about myself: I’m an interdisciplinary urban planner with a BSc in architectural engineering, a MSc in urban policy making and implementation and following that I moved on to work on the intersection of urban studies and media studies and after my PhD in Planning Building Environment I began to focus on smart cities and the use of digital technologies in in urban planning and it was mainly in computer science fields. I try to intersect different disciplines and mainly focus on the regions of Africa, Europe and the United States.

What is a smart city?

So let me give you just a brief overview of what a smart city is. According to the European Union, smart cities use technology mainly to provide solutions and improve their efficiency and management.

It’s basically about collecting different sorts of data, which is used to inform decision-making for building better cities.

In general, the IoT is used within this context to create more smarter energy systems, smarter mobility, and trying to integrate a more efficient digital urban development.

In the literature concerning this topic there are mainly two narratives for smart cities. One narrative focuses on the politics of smart cities, its organisation and society. And the other narrative is the digital perspective which focuses on the use of data, algorithms and devices to build, for example, energy efficient systems or climate friendly systems and so on.

What I will try to argue today is that IoT will sit in the middle between the analogue and the digital by building more social technical systems to create more efficient and smarter cities but also more inclusive cities.

Sustainable investment

Globally the investment in smart cities is increasing and a prime example is Masdar in the United Arab Emirates and there is also a new administrative capital in Egypt being built, both with substantial investment.

Usually most of these investments are about increasing efficiency, creating more efficient cities, but more recent discussions have focused on how IoT systems can be more inclusive and trustworthy.

This has led to a shift from speaking about smart cities towards other concepts such as smart regions, smart countries and smart societies.

However, this is not as popular as simply talking about smart cities. And maybe that’s because of the urban, geographical dimension, but it reflects a more socio-technical entanglement not just in cities but beyond.

Technology solutions

We noticed in a recent publication that there is a movement that started in 2013 basically coming more from computer scientists and it was merely addressing the use of digital technologies from a very technical dimension to see how to build cities to provide technology solutions.

In the same year there was a book published Against the Smart City by Adam Greenfield and it was basically trying to argue against smart cities taking the case of Masdar city in the United Arab Emirates.

And since then, we noticed that there are actually several other movements which try to provide a more social dimension for smart cities such as the movement for inclusive smart cities and a paper entitled Smartness from Below by the anthropologist, Katrien Pype.

Now there are other disciplines speaking about smart cities and interrogating the use of IoT technologies and big data.

So what I argue today is that maybe there needs to be a new movement which tries to link more the socio-technical and the hybrid, I would say the top down, bottom up procedures in the developing smart cities and IoT systems.

Co-production processes

And for this I propose trying to develop more co-production processes and co-create smart cities.

I argue that the interdisciplinary knowledge and co-production can be a systemic innovation policy approach that integrates missions targeted to solve societal socio-technical challenges.

So in smart cities, it’s basically about using big data. Using IoT devices and autonomous machines and sensors to collect massive amounts of data and collating it for decision-making.

The knowledge co-production is an approach to data collection in science that emerged in the 1980s and especially in urban studies to understand who actually produces knowledge and science beyond universities.

So collecting information in this way as a co-production enables us to rethink how we collect the data crucial for smart cities to work. For smart cities to operate, they need data and what I’m trying to explore is how we can co-produce data. Not only co-produce knowledge, but also give more agency to the different stakeholders to be part of the decision-making in smart cities.

So I try to look at the data as a non-human actor and also as the human actor and try to question whether in smart cities the technological tools can become more active or become more responsive to citizens and vice versa. So essentially help citizens to become more active rather than technology taking over and citizens disappearing in this process.

We see it especially in AI systems but also in IoT systems but it can be traced and in a methodical and beneficial way.

Martin: Thank you. Thank you. We’ll save the questions for the final session. Our next speaker is George who’s going to talk about decentralisation and platform migration.

George Zoukas: Decentralisation and Platform Migration: Lessons Learned and Expectations’ by George Zoukas.

George: Hello, everyone. I am very glad to be here, it’s my honour. I’m a Science and Technology Studies postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Like Vassilis I completed my PhD at the University of Edinburgh and I have some background in technology. And one of my interests includes online communication and the history of online communication within the context of climate and environmental communication.

In April 2022 on exactly the same day that of the acquisition of Twitter by Elon Musk was officially initiated, Mastodon, the largest decentralised social media platform, which has operated since 2016 uses its competitor Twitter to promote the benefits of decentralisation and the benefits of moving to Mastodon in particular.

So independence appears to be the main advantage of Mastodon as people can now use a social media platform where its developers for instance claim we have no power to define your rules to show you ads to track your data by design.

However, the idea of independent online communication and its association with the process of decentralisation is not new, given it first appeared at least 45 years ago with the initiation of Usenet, the centralised computer-based communication system distributed in different locations on LAN.

Usenet: an inexpensive alternative to Arpanet

Usenet was developed as an inexpensive alternative to Arpanet, the latter generally regarded as the official ancestor of the internet, with the aim of providing an independent way of communicating online.

Usenet was distinguished by its antibureaucratic ethos of collaboration, egalitarian is and a bottom-up democracy, according to which users were the only ones who decided how to control their content.

So that sort of promise, we could argue, of Usenet was mirrored not only in its decentralised and distributed function, but also in the way it was designed from the very beginning.

Usenet was arranged into a very large number of topics of specific online discussion groups called newsgroups, which in turn were organised under different thematic groups and subgroups.

Deteriorisation of Usenet

However, due to its commercialisation and increasing openness to the public, which began in the early ‘90s Usenet eventually deteriorated. What started as a platform for topic-specific and constructive discussions, mainly by non-computer experts or any other well-informed computer user, was transformed into a platform dominated by an anything goes spirit that could not support any sort of productive or viable interactions.

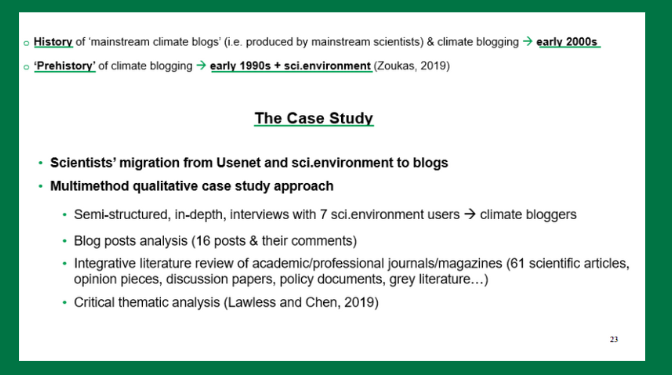

So in this paper, after giving some background information, such as the history of Usenet, I developed my case study around the sci.environment group.

Sci.environment was concerned with subjects focusing on the environment, ecology and sustainability including climate science, climate change and climate policy.

This study is a follow-up on my PhD project, which was about the appropriation of a blogging platform by medical scientists for climate communication.

Migration to climate blogging

I was specifically interested in exploring some of the fact findings within my PhD. In particular, in my PhD, I found that the history of what I describe as mainstream climate blogs and the practice of climate blogging in general dates back to the early zeros when a small group of scientists become utilised in a blogging platform for the communication of climate science and climate change.

What we could describe as the prehistory, so to speak, of climate blogs can be traced back even earlier in the early ‘90s to the environmental news group. This is all because a small group of environmental users, all of them scientists, interest climate science and climate change eventually moved to the blogging platform using blogs as a tool for climate communication.

In this paper I focused on it the scientists’ migration from Usenet to Sci.environment to blogs. I use a multimethod qualitative case study approach with semi-structured, in-depth interviews with seven of the Sci.environment users who eventually moved to climate blogging, blog post analysis and an integrative literature review of academic/professional journals/magazines (61 scientific articles, opinion pieces, discussion papers, policy document and grey literature).

Most of the blogs related directly to some aspects of the history of online communication and I found them an especially good source for data, specifically given that in this kind of historical study if you want to interview people who were using something 25 or even 30 years ago it is difficult to find them

Social, cultural and technological factors in platform migration

So why did a small group of scientists move from Usenet to blogs? I was specifically interested in the social, cultural and technological factors involved and the character of that migration.

And finally, I was interested in how we could use the example of Usenet to analyse current examples of platform imigration, especially from decentralised platforms to the centralised ones. For instance, the migration from Twitter to Mastodon.

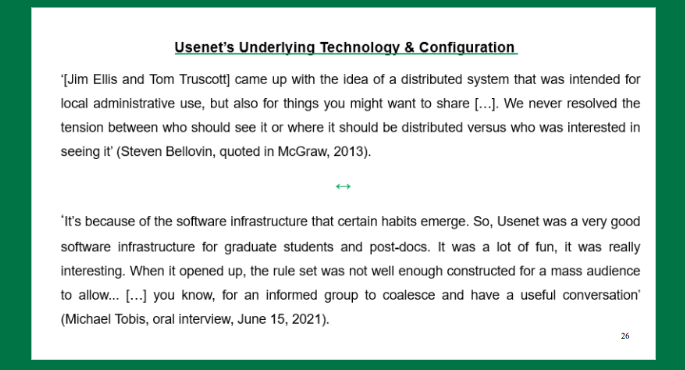

Usenet was designed from the very beginning as a platform for an informed if not expert audience. For people who are interested in using this technology and computer technology in general. The aim of informative and constructive discussions remained with additional theoretics such as psychotherapy being added.

The first quote in the slide comes from an interview with Steven Bellovin, which was published in 2013, who was one of three main developers of Usenet.

The second one comes from one of my interviewees, a regular participant of both sci.environmental newsgroup and later on as a climate blogger.

Now, although his first sentence might sound somehow the deterministic, I really like the way he understands and describes the interrelationship between technology and what could be defined as social or cultural practices.

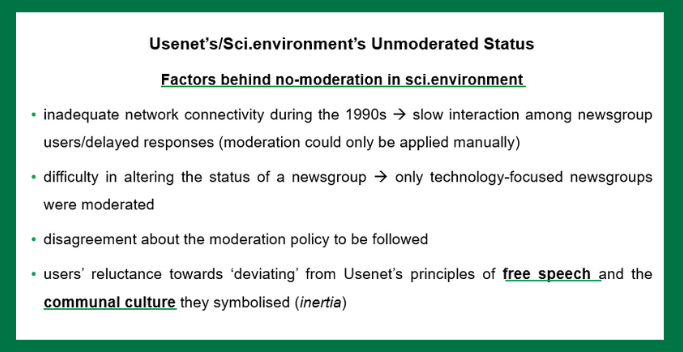

Apparently the commercialisation and the distribution of Usenet into a very, very broad audience was indeed seen by everyone as a main reason for its decline. Usenet was almost exclusively and unmoderated platform. Almost all of its newsgroups were unmoderated and this was the case with sci.environment as well.

No moderation

The main reasons, again based on mandatory data, that no moderation was applied in the newsgroups appears to be the slow network connectivity in the ‘90s. Also, the fact that the moderation could only be applied manually. The difficulty in changing the status of a newsgroup, for example, from unmoderated to a moderated one, seems to be the result of the people who have some kind of expertise in computers being the only ones able to make those changes. So only technology-focused newsgroups were moderated.

There were also some, what I could describe as, practical issues, disagreements about the moderation policy to be followed among the regular participants of the newsgroups.

One of the interviewees, for example, explained to me that even though they tried to apply some sort of light moderation it was difficult to draw the line between what is acceptable and not acceptable.

The final factor, which I emphasise a lot in my paper is what could be described as some kind of inertia among the participants of sci.environment, a reluctance deviating from Usenet’s principle of free speech and the communal character that those principles represented.

This reluctance could be demonstrated not only because no serious effort for moderation was actually made, but most importantly, and as the interviews show, the immigration to blogs took a surprisingly long time, and while there former sc.environment users were on blogs they decided, unsuccessfully as it proved to be the case, to revive the free speech culture of Usenet and the informative and constructive discussions that used to take place there.

I really like this phrase by one of the regular sc.environment users and afterwards climate blogger who posted on his blog: “The great virtue of Usenet was that no-one owned it and anyone could post. The great vice of Usenet was that no-one owned it and so anyone could post.”

I like this because it’s somehow indicative of the main paradigm or of the main argument I put forward in my research paper.

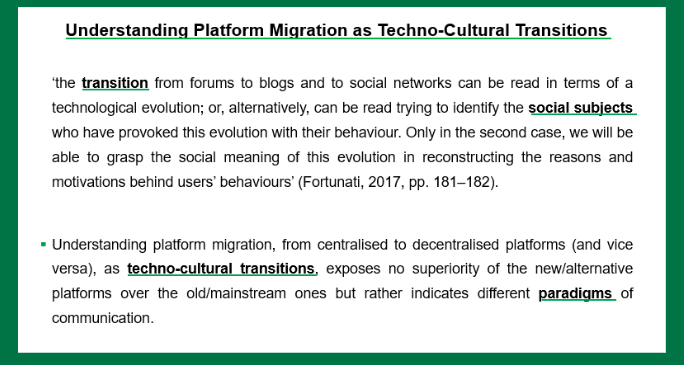

Techno-cultural transitions

This above quote is from Leopoldina Fortunati from an article published in the introductory issues of the Internet Resource Journal.

And the argument I put forward is that to understand platform migration from centralised platforms to decentralised platforms and vice versa, as techno-cultural transition, exposes no superiority of the new/alternative platforms over the over the old/mainstream ones but rather indicates different paradigms of communication.

Now going back to the Mastodon case, I have a very open question which I don’t know if there’s some time to discuss at the end. Its developers highlight, or I have highlighted, that it is a decentralised structure by design. So, the question I want to pose is how can this decentralisation operate in a communicative environment, the establishment of which was essentially the main reason for the decline of the centralised online communication almost three decades ago?

I think I should stop here. Thank you very much. Thank you.

Panel Discussion and audience questions

Martin: I wasn’t a great user of Usenet and my experience of it was that it was not particularly polite, it was quite forthright. Whereas my limited experience of using Twitter is that it’s quite toxic. Is that a fair characterisation and could you explain why if that’s is a correct statement?

George: Usenet became toxic after the early ‘90s, when it was commercialised to a wider audience and everyone could have access to it. Before then, it was especially difficult to access it as it could only be done through university computers.

Usenet itself was launched as an alternative to Arpanet and the case with Arpanet was that only universities with the agreement of the US Defense Department could have access to it. Usenet allowed more universities and their students, mainly graphic design and computer students, to communicate online outside of the Arpanet.

But even so, the audience of Usenet was, until the early late ’80 to early zeros relatively limited. this meant people were able to control their discussion in the sense that they had some sort of a cultural norms that they would all follow in order to have constructive discussions, without the necessity of any moderation.

But things changed, rather an immediate change in the late ‘80s, and by mid-90s it was toxic Just like people describe Twitter today.

Woman in the audience: I’d like to comment on that. The key difference between Usenet and Twitter is that Usenet was divided by topic into hierarchies, whereas Twitter is one giant pool of postings where you have to find the stuff you’re interested in.

And that was a significant change. The change from topic-based communication among strangers to general communication among people who knew each other.

This is the really big change that happened between Usenet and Twitter.

George: Yes, I agree. One of the things that the interviewees mentioned to me when we finally entered the social web era, they still found it difficult to create some sort of focus. When they started using blogs it was difficult for them as the groups of participants were rather limited. And some of them even used the option of using Usenet in order to advertise their blogs.

Woman from the audience: Also, a lot of discussion retreated to web forums and mailing lists, it wasn’t just blogs.

Vassilis: This is a mutual kind of comment that for all speakers about expanding more on the role of culture. I think in George’s case, interestingly in the past year we’ve seen this sort of first attempt at migration from Titter to Mastodon that failed completely and now Bluesky is the is the new thing where you need to know someone to hook you in and I think the difference there is something that David Lyon describes as surveillance culture.

So the difference between Usenet and Twitter was that on Twitter you could get instant verification, snackable verification. You could get likes and people would comment and repost, and Mastodon didn’t offer that.

Mastodon is for the academic I guess echo chamber. On the other hand, we’ve got the hacker culture in terms of Brian’s talk, so in Steven Levy’s Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution is this idea that a hacker can do a positive thing that was then reappropriated by police forces who had the black hat hacker, the white hat hacker, the great hat hacker.

So these kinds of terminologies are emerging and in Mennatullah’s talk I think we have to consider local cultures and how they respond to smart cities as a potential for surveillance as well. There is a great paper from another one of our colleagues, José Gómez, who looked at Ecuador and the prospect of a smart city of the future and how it failed essentially because local citizens rejected it.

George: Mastodon still exists, and I think the word failed is a bit strong because it was built less than ten years ago. It’s a small period of time, so I think that there might be some changes. I’m not very optimistic, but we can hope.

Eva Pascoe in the audience: Yeah, I’ve got a quick question. I remember being a user of Usenet back in the ‘80s and it was predominantly populated by students and it was pretty rude in a studenty way. You know, including nasty porn and all sorts of crazy stuff. But it was pretty manageable.

What changed was when the AOL has opened a gateway [1994] and a lot of extremely unpleasant Americans joined and it never really recovered.

So, the thought I had at that time, and it was breaking my heart to lose my communities, was that it was completely unacceptable to stay there. I took an etiquette course at Cyberia Café back in the ‘90s and it was the case that communities always tried to raise the level of technical difficulties and there were a self-selected set of people who were happy to accept certain community rules.

So where the refugees from Usenet drifted off to were places which were harder to be owned. Where the direction of travel was opposite, things were getting easier i.e. Twitter, that was basically where the American rudeness emerged and things have gone downhill ever since.

I think Mastodon is slightly technically more demanding. So there’s that sort of continuing escape to quality by making things a touch harder to access.

Jim Norton in the audience: One for Brian really, I wonder if sometimes the hacking attempt of disruption can be entirely accidental. There’s the wonderful case of the IBM Christmas card. This was created in the University of Florida by a student who was using the VM network to create a Christmas card that self-replicated when you put it into somebody’s mailbox and sent itself to all the others in the mailbox.

And then IBM did the one thing guaranteed to make a bad situation completely impossible. They sent by separate means, messages to every IBM in office globally saying on no account open the Christmas card that comes into your mailbox.

So IBM staff assuming it was porn rushed to see and there were trillions of Christmas cards in circulation across global VMs and they had to shut it for 72 to flush the entire network of these things.

Brian: One of the things I came across was a hacker got into a computer used in cancer care at the Sloan Kettering Memorial Center. And one of the common responses at the time period was, well, they’re just kids and they’re helping expose security so give them an account. And actually, the administrator there gave the hacker an account and the hacker was like, ‘I don’t wanna stay in the box’ and he kept breaking out and messing things up. So there were a variety of responses to it and in that case it was unintentional disruption that wasn’t malicious where didn’t quite know what he’s doing.

Robin Mansell in the audience: My question is for Mennatullah. I was particularly interested in what you said about smart cities. Citizens tend to disappear and also said that what we need more of is co-production of data.

And my question to you is about that co-production process because I think there are many studies that show that co-production can sound good. But in practice, the citizens would need to be involved in the co-production rather than money, time resources. But I just wonder what your experience is in yours more recent studies of smart cities. Do you see hope that that kind of co-production is realistic or are you pessimistic that the citizens continue to disappear?

Mennatullah on Zoom from Cairo: I think I tend more towards being pessimistic about it. But I would say it’s a study still under progress and what we want to do is do kind of a kind of an experiment and to exactly try to figure out what you mentioned and to try to understand how citizens may prove that can have more agency in the process and to ask if this is actually possible or not.

I personally have the impression that actually using more technological tools more citizens disappear.

Man in the audience: Thanks for all these talks. I’m a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford and serving this year as the lecturer in socio technical systems at a small institution here in London. I’ve been a programmer, software engineer and now I work with lawyers on workers’ rights issues.

My, question for all of the panellists. I’ve been chewing on these talks from this morning and this afternoon and the theme that I feel is starting to emerge, especially with Mennatullah’s response just now, is that sometimes we become convinced that we can really solve social problems or political problems with a new technology.

14:39:43 And every once in a while, some new generation of technology comes around and the people who thought they’d learned to know better from the last generation of failed promises are sort of convinced that oh no this time it’s going to be different and I have two questions to the panellists.

The first one is, is that right – are we sort of in this cycle of thinking? And we, maybe not those of us in this room, but decision-makers, policymakers, company executives for making these decisions. Do they really believe that we’re really going to use technology to solve social problems and has that ever worked?

And the second question is, is there a sense that this time is different and what do we think about that if there is?

Brian: I think there’s definitely the perception out there that technology can improve social problems. It’s hard to say whether motive wise that’s a justification.

If you look at a lot of the big tech, the idea of long-termism and stuff like that. My humble opinion is they’re just justifying what they’re doing to try to make themselves look good.

You know, there’s always this tendency, what was the saying? ‘Every generation thinks they’re the generation that discovered sex’.

That everyone is saying our technology is better than before. And there’s both the trademark that we keep on replicating the same errors of the past, but also how many people were dying in steam boiler explosions today.

There are a lot of small incremental improvements as technology gets better. I fed myself in college by fixing people’s computers in exchange for pizza. I wouldn’t be able to make that living anymore because they just don’t break like that anymore.

So it’s both replicating the same big picture items but there has been change. The issues are both the same, but they’re also different. We’re not making the same mistake over and over. We’re making adjacent mistakes over and over.

John Carrington: As I said right at the beginning with my experiences in cellular. The solutions originally were for places like the UK, Europe and so on and so forth.

One of the biggest impacts has been in Africa, in the Middle East, in Asia. I know when I first went to India in the late ‘80s early ‘90s the telecoms penetration was incredibly small. Now they are as communicated as we are in Africa. I saw some fantastic things in South Africa during transition. There the technology used by people for ways that I could never conceive to provide people with credit with pay phones. So that’s one where the technology I think has gone beyond the initial expectation to provide liberation.

Paul Excell in the audience: Is there also a thing about trust and technology? So for example, people have been driving around in cars forever and people seem to accept, and I hope this is not insensitive to anybody in the room, that there will be a certain level of fatalities and accidents, however, when you have one driverless car have an accident it’s kind of splattered everywhere.

Are there any lessons from history where you’ve seen that trust equation change?

George: I see a difference between trusting science and trusting technology. So whether we can see several cases in which people do not trust science, which one common case is that of COVID vaccination.

Technology is really more intrusive. It becomes part of our everyday life, that we don’t always understand, so trust is built.

Brian: On the risk side I think it’s well documented that people are really bad at assigning risks. I mean, we’re talking about well-documented communication systems here. I think most people would say that that ultimately is a very, very safe form of technology as opposed to say nuclear reactors, but on the other hand, I think you can make an argument that they’re actually profoundly much more dangerous by what they enable. It might not blow up, but I don’t know how you compare such desperate risks and how would you weigh it in response to those things?

Martin: We probably should stop there. Thank you all.