Telephone helplines may, at first, seem like an unusual topic at a forum on norms for the digital age. However, as I will discuss in this paper, helplines were important in establishing the concept and practice of receiving information and advice ‘on demand’ through technological mediation. Initially established as a tool for marginalised communities in the later 1960s, the helpline model grew in the 1970s and 1980s, in course shifting mainstream expectations about how one should obtain information and interact with government. Contrary to recent policy and industry hypes around digital technologies, telephone helplines are by no means obsolete: in the 2010s, 60 million calls to helplines were made each year, and this volume rose further during the Covid pandemic and subsequent cost of living crisis in the 2020s.[1] Telephone helplines are therefore an essential part of the mixed economy of welfare, and a critical tool in helping the public ‘fare well’ in twenty-first century Britain.I will first look at the growth of helplines, and then look at the establishment of norms in the 1980s and 1990s.

***

Telephony emerged in Britain in the later part of the nineteenth century, initially provided by various private companies or city corporations. Although the middle classes were early adopters of phones at home, market saturation of domestic landlines was not reached until the 1980s, in sharp contrast to the runaway popularity of television and radio. Douglas and Isherwood argue that the telephone was slower to establish itself through its origins as a business technology that the middle classes were familiar with from using at work, enabling them to see the benefits that would follow from installing one at home.[2] Such benefits could be quotidian, such as ordering groceries to be delivered to one’s home, but they could include, as Moss has shown, privileged access to the emergency services through being able to call, from 1937, 999 from the comfort of one’s home.[3] Domestic landlines were not the only way of making personal calls, however. From the 1880s, some businesses allowed people to use their phones for a small charge. As Linge and Sutton note, these ‘public call offices’ were often in busy areas, close to train stations or shopping areas. The equipment was built into cubicles that allowed the caller privacy, developing later into the phone box. When the General Post Office took over telephone services in the early twentieth century, such phone boxes spread across the nation. By 1935, 20,000 phone boxes had been installed. Phone boxes continued to grow, with 132,000 British Telecom phone boxes in use by the 1990s, the peak of the phone box.[4]

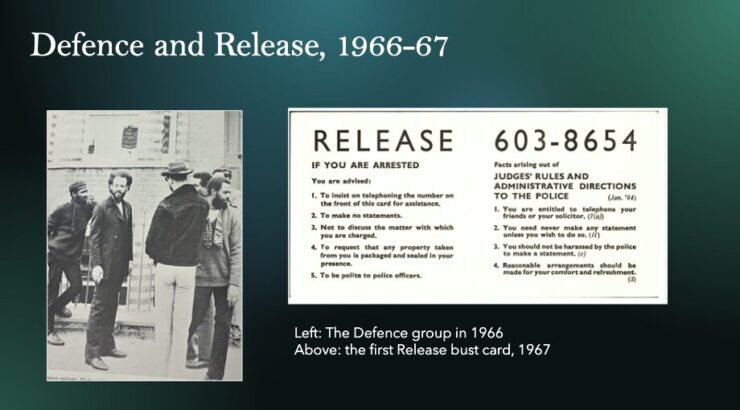

Using a phone to summons help was established early on. Before the introduction of 999, one called or was connected by the operator to the local number for the police or fire brigade.[5] The first helpline of sorts was offered by an unnamed East London clergyman in 1926 in a short-lived experiment. Callers to East 0548 who asked ‘for the servant’ would be able to obtain advice from him on any matter, provided it was not financial.[6] The Samaritans were founded in 1953 by the Reverend Chad Varah, who was concerned that people experiencing an emotional or mental health crisis could not obtain help outside of standard working hours. Calling MAN 9000 would enable a caller to reach a team of volunteers who would listen to them without judgment. By 1963, there were 14 ‘Samaritans’ groups in the UK, all of whom had, like Varah’s original group, a specially selected number to call.[7] A combination of police racism and a harsher regime introduced by the Dangerous Drugs Act 1965 led to an increase in arrests of Black people in West London.

Defence was set up in late 1966 to offer a 24-hour telephone line that could connect people to a sympathetic and supportive solicitor.[8] Defence was short-lived, but it informed the foundation of Release the following year, who likewise used a 24-hour telephone number as a first step in helping people who had been arrested on drugs charges.[9] However, it was readily apparent to Release that they also needed to support people with other issues, such as housing or benefits, and Caroline Coon, its co-founder, described Release as ‘the welfare branch of the alternative society’.[10]

Defence and Release inspired similar helpline activity in and around the counterculture and anti-racist activism. However, Release was close to an area within the counterculture that was interested in the potential of information for radical social change. BIT was a 24-hour information line that was founded in 1968 by John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins as a side project to the countercultural newspaper he was involved with, the International Times.[11] BIT’s remit was to provide ‘general “underground” info’ to anyone who called the line or dropped into its premises in West London. Whilst this could and did include information on events, arts, activist groups and the like, BIT also provided guidance on welfare benefits, squats and crash pads, jobs and travel. BIT workers had access to a library in the offices, managed at one point by Nicholas Albery, who worked the night shift there between 1968 and 1974.[12]

Proliferation of helplines in the late 1960s

Helplines began to proliferate from the late 1960s because they were relatively easy to set up – to set up Release, Coon spent some of her art school grant on installing a phone in her flat.[13] They offered timeliness, but also anonymity. This was vital for the groups of marginalised people they sought to support, for whom face-to-face or identified contact with the authorities could be highly risky. For people with disabilities that impacted upon their mobility, helplines removed the need to travel to an office for advice or information, and thereby the risk of getting there to find that the building was not accessible. For less common issues or problems, a helpline could have a far greater reach than a locally organised group. Helplines also offered potential for those with experiential expertise to share that with others, which could offer a very different type of advice and help to that offered by ‘mainstream’ professionals.[14] They were also a space in which ‘counter-professionals’, as Inch et al describe them, could practice – those solicitors, doctors, social workers etc who were aligned with the counterculture or community action.[15]

The proliferation that began in the late 1960s and early 1970s also resulted in helplines moving away from radical action to the mainstream. The Citizens Advice Bureaux were initially reluctant to move away from an office-based, face-to-face model of offering advice.[16] However, the transformative potential of the telephone was pushed by people like Michael Young, whose National Innovations Centre supported various projects in the early 1970s, such as the Bath Advisory Service.[17] Helplines also offered strong potential for crossover work with media companies.

The Capital Radio Helpline was founded in 1976, offering callers a 24-hour line that could be called for advice and information on any topic.[18] Interactive or crossover services of this kind were not new. The tabloidization of newspapers in the later nineteenth century had created the ‘reader offer’, and by the interwar period, this included write-in advice bureaux. Professor John Hilton’s BBC broadcasts and articles in the national press on a range of common problems resulted in thousands of letters being written in by the public seeking help and, in 1942, the News of the World launched the John Hilton Bureau which offered expert responses to individual letters. The Bureau was wound down the early 1970s, replaced by a telephone line offering a menu of pre-recorded advice topics.[19] For the BBC, however, helplines could be part of their public service broadcasting remit. Childline emerged in 1986 from Esther Rantzen’s Childwatch BBC broadcast, which she pushed for after reading about the death of a small child because of parental negligence.[20] The BBC launched its Action Line in 1995. At the end of broadcasts that explored challenging topics or themes, the Action Line number would be (and still is) given to enable viewers to be connected to someone from a helpline.[21]

Satire and sarcasm about helplines accompanied them from the start, whether that was Punch making fun of students setting up Nightline helplines in the 1970s or opinion columns in the 1990s bemoaning ‘yet another’ helpline being set up to deal with a particular issue.[22] Helplines were also part of the entertainment landscape, cropping up in dramas and sitcoms, such as the 1996 Game On episode in which Martin volunteered at the fictional ‘Nightwatch’ helpline to try to impress a romantic interest.[23] Such representations hit down at helplines without considering the impact they could have for people who didn’t know professionals that they could call up for a discreet chat or who might feel isolated from the people around them.

The critique was also out of step with official use of helplines by the 1990s. The Inland Revenue had used helplines from the early 1970s as a way of aiding people with changes to tax or pensions, and the Benefits Agency, launched in 1991, offered a general social security benefits line that took more than three million calls each year.[24] Whilst some official phone lines attracted derision – the motorway cones hotline or the ‘shop-a-benefits-cheat’ line – the majority were an effective way of enabling the public to interact with the state.[25] The telephone and the helpline were central to the emerging vision of modern government in the 1990s, particularly as it was articulated by Tony Blair’s New Labour.[26]

The 1999 Modernising Government White Paper outlined a commitment to ‘making public services available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, where there is a demand.’[27] It called for the creation of ‘one-stop shops’ to help people navigate public services, which did not need to be bricks and mortar, but ‘available via the telephone or the Internet, such as the MOD’s Veterans’ Advice Unit or Business Links.’[28] Modernising Government also laid out standards to be achieved by the end of the year 2000, namely the rollout of NHS Direct and the ability to apply for jobs through the Employment Service using the phone or internet.[29]

It is important, however, not to see this as a linear, Whiggish development of helplines from their radical origins to influencing government. ‘Good’ calls did not magically happen, and working out that this should look like was an iterative process. Training was one element of this. When the Samaritans launched, Varah was an Anglican priest with two decades’ experience of counselling as well as supporting the pastoral needs of his parishioners. He described his first calls as involving ‘gentle discussion, with more listening than talking’.[30] Varah initially took the calls on his own but began to hand over the calls to the volunteers who had come on board to support him. Rather than using the volunteers to assist people waiting to speak to Varah, it became clear that the volunteers were effective call takers themselves.

At the outset, Varah chose his volunteers through his subjective perception of someone’s personality, and how confident he felt that they would actively listen to callers and not offer advice or judgement. They also had to agree to handling calls in the strictest of confidence.[31] Organisational growth brought with it new needs for communication and training, with regular ‘Schools’ established for the branches to come together each year to share information about emerging issues and best practice.[32] For helplines that provided information, ensuring that call handlers either had the requisite knowledge or access to a resource library that they could consult was essential. Whilst shadowing ‘Dorothy’ of the Capital Radio Helpline in 1978, journalist Carol Sarler described the information library available to the staff and the wall plastered with important notices and phone numbers so that callers could be given accurate referrals onwards.[33]

Not all helplines were as they seemed

Following the legalisation of abortion in specific contexts through the Abortion Act 1967, concerns were raised that helplines for girls and women considering the procedure were not what they seemed. For example, the Youth Development Trust in Manchester undertook a survey in 1974 of support available to pregnant young people. They were concerned that commercial abortion agency helplines were pressuring girls and women into committing to have an abortion and spending up to £150 in the process.[34] In 1989, a major advertising campaign for a 24-hour helpline that offered to put callers in touch with trained counsellors omitted to include details about its provider: the Morris Cerullo World Evangelist Society of Great Britain. A young girl calling to ask for help with an unwanted pregnancy was asked distressing questions and asked to pray; a Muslim caller was told to renounce their faith.[35] Tambrands, the manufacturers of Tampax tampons, were found in 1993 to have been providing a peak-rate helpline that gave women advice on toxic shock syndrome. The helpline was presented as providing impartial and independent advice, when this was not the case.[36]

In these examples, the issue was not the helpline provider per se, but rather that the provider’s agenda was, at best, blurred, and at worst, deliberately obscured. In another case, in 1995, the Birmingham Angling Association were disturbed to learn that their pre-recorded messages on local river conditions were being wiped in favour of messages from a sex line. The anglers had rented a line from a private provider which had collapsed, and the line had been sold on, without their knowledge, to others. The Association was stuck with a number that was no longer theirs published on all their membership cards and in the 12,000 handbooks sold through sports shops. BT were unable to help, directing the Association instead to the Independent Committee for the Supervision of Standards in Telephone Information Services.[37]

The Brenda System

Bad calls could also take the form of abuse being perpetrated by either the caller or the call handler. The Central London branch of the Samaritans developed the ‘Brenda System’ from 1973 to deal with the problem of female volunteers being subjected to nuisance calls.[38] Using the phone for sexual abuse was not confined to callers. In 1995, a Cambridgeshire police constable was sacked after he used his work on a police helpline for people in distress as a means of obtaining women’s phone numbers to make anonymous sexual calls – from his desk in the police station. This came to light when BT traced the source of the calls.[39]

The cases here identify serious issues that needed urgent addressing by the 1990s: that helplines were what they purported to be; that helpline staff and callers were protected from harassment and abuse; and the need to regulate a sector that was privatised during the 1980s. The Independent Committee for the Supervision of Standards in Telephone Information Services was founded in 1986 to deal with the issue of how BT and other network operators were building profits from premium rate numbers and trying to prevent consumers being exploited through chargeable items to their phone bill. The Committee was later renamed, eventually becoming the Phone-Paid Services Authority, an arm’s length regulatory body under the Department for Science, Industry and Technology.[40] If this was a move to manage the phone network providers and those providing paid phone services, there was also an important move around the same time to build confidence and capacity in the welfare helplines sector. The first industry group in this area was formed in the late 1980s, when the Telephone Helplines Group was formed of representatives of larger, established helplines and charities, like the Samaritans and the NSPCC. The group worked with and lobbied British Telecom to deal with the unintended consequences of innovation: confidentiality could be compromised by caller ID services revealing the caller’s number to the helpline, whilst itemised billing could lead to an individual’s call to a helpline being revealed to others, putting them at risk of embarrassment and challenge at best or in mortal danger at worst.[41]

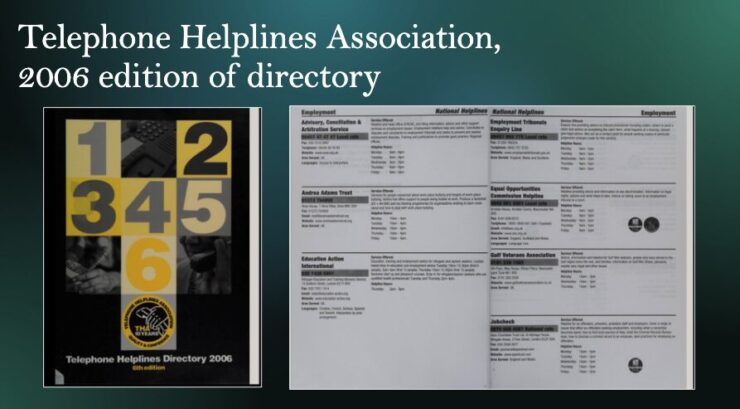

To try to mitigate the impact of ‘rogue’ helplines, in the run-up to the formation of the Telephone Helplines Association in 1996, members of the earlier group compiled a directory of welfare helplines. From an initial run of thousands of helplines, the compilers used a questionnaire to identify helplines that they felt met the criteria and threshold for inclusion.[42] This directory, first published in 1996, offered a curated list of 800 helpline providers that could be consulted in reference libraries, by professionals and by helpline staff and volunteers.[43] The establishment of the Telephone Helplines Association allowed the sector to maintain communication with BT and other network providers, but also to develop a space for sharing good practice, training, and brokering access to technology.[44]

In conclusion, helplines began as a rapid, DIY response to the challenges experienced by marginalised groups in the 1960s and 1970s. They proliferated because of the relative ease of setting them up and the benefits they offered to both providers and callers, and both mainstream charities and the state embraced helplines and hotlines. This was also part of a wider embrace of the telephone, as domestic landlines increased, the payphone network reached its peak, and the mobile phone market began to grow. Seeking help on the telephone became normalised, as did using the telephone for other tasks, such as banking or shopping – one norm, then, was using the phone to seek information and help on personal issues, either by coming across details of a helpline in the newspaper, in a directory, or having seen a television programme on a relevant topic. Helplines were far from unproblematic, however, and considerable energy went into professionalising and regulating the sector to protect both the public and legitimate callers. Helplines emerged before online services, and they now coexist. However, the ways in which helpline providers had to work out how to create positive norms and to challenge poor practice are echoed to an extent in the 2020s, as in the Online Safety Act 2023.

[1] Toni, ‘UK Helplines Awareness Day – “Happy 2nd Birthday To You!”’, Energy Advice Helpline (blog), 19 February 2024, https://energyadvicehelpline.org/uk-helplines-awareness-day-happy-2nd-birthday-to-you/.

[2] Mary Douglas and Baron Isherwood, The World of Goods: Towards an Anthropology of Consumption (London: Routledge, 1979).

[3] Eloise Moss, ‘“Dial 999 for Help!” The Three-Digit Emergency Number and the Transnational Politics of Welfare Activism, 1937–1979’, Journal of Social History 52, no. 2 (2018): 468–500.

[4] Nigel Linge and Andy Sutton, The British Telephone Box (Stroud: Amberley, 2017), 7–10, 71.

[5] Ibid., 58–70.

[6] ‘Advice by telephone’, Belfast Telegraph, 22 June 1926, p.3.

[7] Chad Varah, The Samaritans: Befriending the Suicidal, Revised (London: Constable, 1985), 24–28.

[8] Colin MacInnes, ‘RAAStus: WI in W2’, Oz, February 1967, pp.14-17

[9] Kate Bradley, Ellis Spicer, and Jon Winder, ‘The Bust Card: Policing, Race, Welfare, Drugs and the Counterculture in 1960s Britain’, Modern British History, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/tcbh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/tcbh/hwae062/7928242; Kate Bradley, ‘Over-Policed and under-Protected: The Black Community and Legal Activism in London, 1965-1975’, Historische Anthropologie 31, no. 2 (2023): 242–62.

[10] Caroline Coon, ‘We Were the Welfare Branch of the Alternative Society’, in The Unsung Sixties: Memoirs of Social Innovation, ed. Helene Curtis and Mimi Sanderson (London: Whiting and Birch, 2004), 183–97; Alex Mold, ‘“The Welfare Branch of the Alternative Society?” The Work of Drug Voluntary Organization Release, 1967-1978’, Twentieth Century British History 17 (2005): 50–73, https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwi064.

[11] Flip Wibbly Jelly, ‘BIT’, Hoppy X (blog), 13 October 2016, https://hoppyx.com/timeline/bit/. Accessed 2 January 2025.

[12] Alan Beam, Rehearsal for the Year 2000 (Drugs, Religions, Madness, Crime, Communes, Love, Visions, Festivals and Lunar Energy). The Rebirth of Albion Free State (Known in the Dark Ages as England). Memoirs of a Male Midwife (1966-1976). (London: Revelaction Press, 1976), 34.

[13] Bradley, Spicer, and Winder, ‘Bust Card’.

[14] See Kate Bradley, ‘Connecting the Disconnected? Technology, Advice, Welfare and Civil Rights in Britain, 1950-1980’, in Everyday Welfare in Modern British History Experience, Expertise and Activism, Palgrave Studies in the History of Childhood (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025), 289–309, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64987-5_13.

[15] Andy Inch et al., ‘Community Action, Counter-Professionals and Radical Planning in the UK’, City. Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action 28, no. 5–6 (2024): 681–704.

[16] National Citizens Advice Bureaux Council, Report of National Citizens Advice Bureaux Council to National Standing Conference of CABX, 1966-68, (London: National Citizens Advice Bureaux Council, 1968), pp.10-11.

[17] Diana Dewar, ‘Aid on the line’, Guardian, 31 October 1973, p.11.

[18] Jenny Rees, ‘Capital Radio’s £14,000 grant’, Daily Mail, 31 August 1976, p.9.

[19] Kate Bradley, ‘“All Human Life Is There”: The John Hilton Bureau of the News of the World and Access to Free Legal Advice, c.1938-1973’, English Historical Review, 2014.

[20] Esther Rantzen, Eve Colpus and Jenny Crane, ‘30 Years of Childline 1986-2016’ (BT Tower, London, 1 June 2016), 7–8, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick; Eve Colpus, ‘Claiming and Curating Experiential Expertise at the Children’s Telephone Helpline, Childline UK, 1986-2006’, in Everyday Welfare in Modern British History Experience, Expertise and Activism, Palgrave Studies in the History of Childhood (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025).

[21] Jasper Jackson, ‘EastEnders and Holby City Inspire Most Calls to BBC’s Action Line’, The Guardian, 29 December 2015, sec. Media, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/dec/29/eastenders-holby-city-most-calls-bbc-advice-action-line.

[22] Jonathan Sale, ‘The government’s job creation programme’, Punch, 8 Sept 1976, p.374; Craig Brown, ‘Ego-mania and the wilful unemployed’, Punch, 12 October 1977, pp. 644-646; Katharine Whitehorn, ‘Don’t mess with me, doc, it’s my stiff upper lip’, Observer, 30 April 1995, p.22; ‘TV Friday: Newsround Extra: The Boy Band-Wagon’, Guardian, 2 March 1996, p.B78.

[23] ‘BBC2’, Guardian, 20 October 1996, p.D84.

[24] David Brindle, ‘End of benefit help line as spending cuts bite’, Guardian, 12 July 1996, p.10.

[25] Brian Wheeler, ‘The cones hotline’s legacy’, BBC News, 6 January 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/7772818.stm

[26] Michael Simmons, ‘Lines of communication’, Guardian, 28 June 1995, p.B6.

[27] Cabinet Office, ‘Modernising Government’ (London, 1999), 23.

[28] Ibid., 30.

[29] Ibid., 33.

[30] Varah, The Samaritans: Befriending the Suicidal, 21.

[31] Ibid., 24–27.

[32] Ibid., 214–22.

[33] Carol Sarler, ‘Allaying it on the line’, Sunday Times, 17 September 1978, p.42.

[34] ‘Doubts on advice services, Guardian, 16 March 1974, p.4.

[35] ‘Helpline adverts gloss over evangelical message’, Guardian, 27 December 1974, p.6.

[36] ‘Toxic Shock shock’, Guardian, 29 November 1993, p.13.

[37] ‘Anglers dialling for advice receive hotter tips than they bargained for’, Guardian, 29 March 1995.

[38] Varah, The Samaritans: Befriending the Suicidal.

[39] ‘PC sacked for sex harassment’, Guardian, 24 Feb 1995, p.3.

[40] See https://psauthority.org.uk/About-Us, correct 2 January 2025.

[41] Michael Simmons, ‘Lines of communication’, Guardian, 28 June 1995, p.B6.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Michael Simmons, ‘Matters Arising’, Guardian, 31 January 1996, p.B7.

[44] Dick Frak, Our Story. The Story of the Mental Health Helplines Partnership (London: Department of Health and Mental Health Helplines Partnership, 2009), https://issuu.com/helplines_partnership/docs/mhhp-our_story.