In 1957 US company Digital Equipment Corporation began when Ken Olsen, his brother Stan Olsen and Harlan Anderson set up a computer firm in a former woollen mill in Maynard, Massachusetts. Their initial aim was to sell logic modules. They met while working as engineers at the Lincoln Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. By the end of the 1970s, Digital (also known as DEC) was to become the second largest computer company in the world, with offices at over 300 sites.

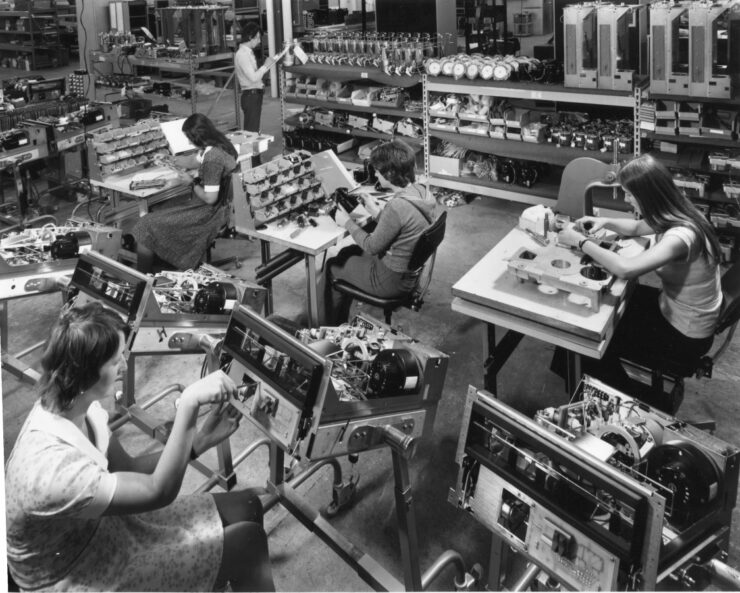

DEC was known for producing some of the world’s first mini-computers. This meant that cheaper, smaller, programmable machines became available to industry, and then the public. These models were known as PDPs and by 1966, the PDP 8 had become the world’s first mass-market minicomputer, with over 53,000 sold.

DEC’s first office in the United Kingdom opened in Reading, Berkshire in 1964. Led by John Leng, with two employees in an office above a furniture shop, their job was to market the PDP computer for educational use. In 1981 DEC’s UK Headquarters was built at Worton Grange in Reading, known as DEC Park. A plant at Ayr in Scotland was built to manufacture systems in 1975. In the 1990s there were more company offices at The Crescent in Basingstoke. DEC grew quickly, and at its peak, employed more than 2000 people in Reading alone.

Managing Director Geoff Shingles joined DEC in Reading as a sales and service engineer in 1965 when it still only had 3 employees:

We positioned ourselves in Reading, which was halfway between London Airport and the Atomic Energy Authority at Harwell, because, our main customers were scientific users, and the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, and the AWE, the atomic weapons place at Aldermaston, were our first and major big customers in those early years.

DEC was known for its company motto ‘Do the right thing’ by the customer, and for its tight knit working atmosphere. The philosophy of founder Ken Olsen, who was a Quaker, inspired employees to dedicate their working lives to the company, often working long hours and even meeting spouses at work. Job interviews were based on behavioural science over skills, which had an impact on work culture. Consultancy Group Manager Keith Saunders explains:

You know, I could go up and I could talk to anyone, no matter how senior, and they would talk to me as though I’m just the co-worker that you work with every day, and that was the DEC way.

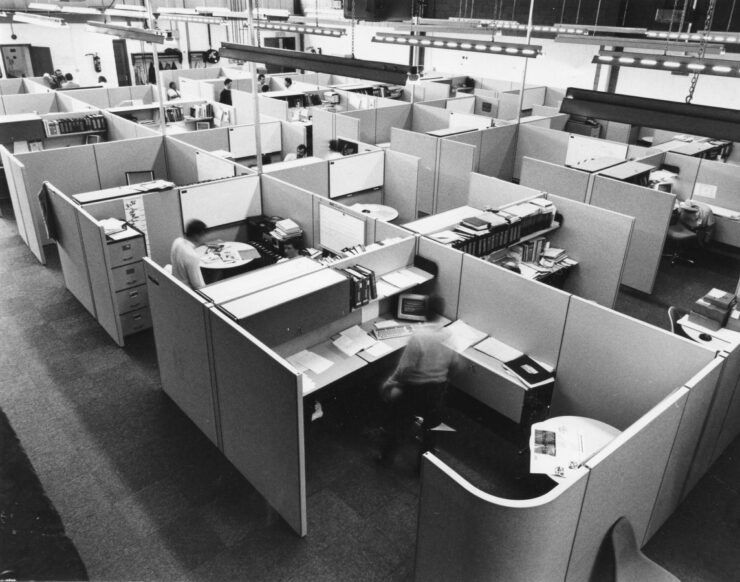

The Headquarters at DEC Park was revolutionary, taking the form of a high street with shops, hairdressers and even a travel agents. DEC had a helicopter fleet which it was famous for at the time as well, mentioned often by people in their memories of the company. Staff were encouraged to move up the ranks in their careers and DEC provided their own training. As an example, Sales manager Simone Hume came to DEC as a temp, and was encouraged to join the DigiTemps Programme, which offered the chance for more permanent roles. Encouraged by her manager, Simone entered the sales environment at DEC and describes the sales training she had there as some of the best she had ever had. It was a new, different way of making sales as well:

All the sales training was all about, you know, how do you sell? How do you sell something that’s not in front of you? If you’re selling a laptop or a computer, you can show pictures that can touch it, feel it, come and see it. If you’re selling a service, a bit like cloud services today, it’s conceptual. Selling you. You have to be able to understand the need or the want of the customer, and be able to explain how the service is going to be able to help them.

Employees often worked at DEC UK and DEC in the USA and Europe, spending time in different countries as their career progressed. Others like Michael Burrows, who was born in the UK, got his first job out of university at DEC’s Systems Research Centre in the USA where he worked with Louis Monier creating the Alta Vista search engine. Shaheed Haque joined DEC in Reading in 1983, working on the DMB 32 project, which involved designing an IO board for VAX computers. He worked in DEC Park 2 in Reading, but reported to DEC USA:

Engineering, we built products to be sold internationally on a large scale. The part numbers that we had, there’d be UK variants, German variants, French variants, whatever. So we were aware of the business people in DEC Park 1, but we reported up through US reporting chains, through US engineering. So we really had very little to do with DEC Park 1 from a organisational perspective.

By the 1980s, hundreds of engineers were pioneering software that automated workplaces with electronic documents and email, exemplified by the DEC ALL-IN-1 program, a precursor to modern tools like Microsoft Office. Meanwhile, Reading-based engineers developed technologies to link computers across vast distances, enabling larger data and voice traffic transfers. DEC was stepping into the 1990s, playing a pivotal role in shaping the Internet as we know it today. For example, in 1987 David Probert came to DEC from BT, where he had been working on a systems project using optical fibre and video conferencing. By November 1991 David was in charge of providing the first international routers in Eastern Europe – essentially at this point DEC was managing the entire European internet.

In the early 1990s, DEC’s competitors started to overtake them, helped along by great improvements in the capabilities of microprocessors. DEC produced hardware and software on a proprietary model, whilst customers were using third party products instead. Sales faltered and staff redundancies began. Conflict in the boardroom saw founder Ken Olsen fired in 1992 and the 1990s were dominated by new CEO Robert Palmer’s attempt to keep DEC competitive by huge redundancy programmes, plant closures and restructuring efforts. An estimate of 60,000 redundancies at this time shows how many people DEC employed around the world at its height.

In 1998 DEC was bought out by Compaq for $9.6 billion in, what was then, the largest merger in computing history. Compaq was later acquired by Hewlett-Packard who remained in DEC Park until 2006, when they relocated to Winnersh. DEC Park was demolished in 2010.

Further Information

- In 2024 Reading Museum ran the project Reading’s DIGITAL Revolution, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and donations from DECUS and local charity RGSpaces. With The National Museum of Computing, they conducted oral histories with past employees of DEC, which are available on our website.

- Find out more about the history of DEC in Reading, by visiting Reading Museum’s online exhibition.

- The Computer History Museum (itself a project that started in a DEC office in Massachusetts) holds an archive for Digital Equipment Corporation, view the catalogue here

- Berkshire Record Office holds Geoff Shingles’ archive from his time working for DEC.

- Digital Equipment in Galway has an online resource of photographs and memories, available here.

- The iconic Digital logo was designed by Eliot Hendrickson in 1957. Find out more about the logo’s history in this blog by Ned Batchelder, who worked with the Logo at DEC.