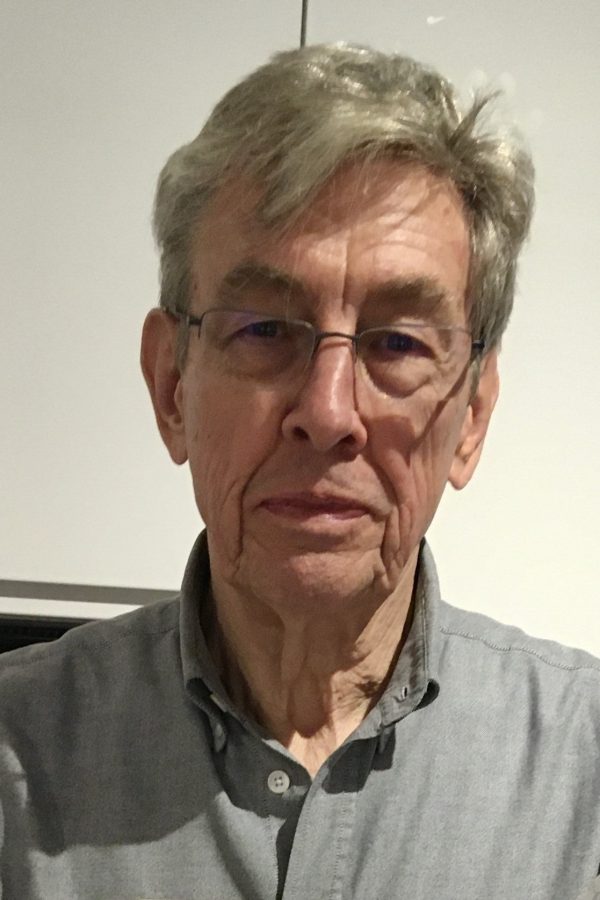

Tim Johnson is perhaps best known to those in IT as the co-founder of Ovum, one of the foremost analysts of the industry, that subsumed another familiar name, Holway, and still produces reports, now as part of Datamonitor.

Tim describes himself as a researcher, a role he has been carrying out since becoming a science correspondent in 1963, producing material on key technologies, markets and issues in various media, through the nationals press and his own brands like Ovum, Point Topic, and Look Multimedia. His pioneering work includes some of the first publications on packet switching, expert systems, video cassettes and the use and applications for data communications across 17 European countries.

Tim comes from a line of ancestors involved in technology and media and his father wrote a report recommending the installation of a computer in the design department of Roll-Royce in 1953.

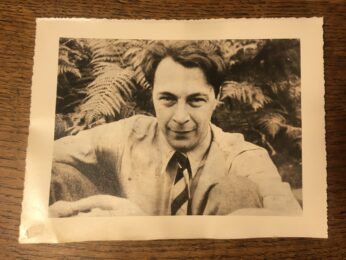

Christopher Timothy Forbes Johnson (Tim) was born in 1942 in Derby. He has a younger brother. His father was a graduate engineer working for Rolls-Royce. His mother studied English at Aberystwyth, then part of theUniversity of Wales. Tim says: “My father got a starred first in engineering and mathematics from Cambridge and his dream was to work on the aero engine side of Rolls-Royce, which was the leading technology company of the time. But when it came down to it, during World War Two, it was all hands to the pumps. A lot of the time he was working on the shopfloor because graduate engineers might not have been the most urgent things they needed.” In late 1952 Tim’s father was commissioned by the company to report on whether they could use a ‘computor’ (the spelling used on the cover of his report). in the design office to calculate the optimum shapes of turbine blades. Tim adds: “The exact design of those blades was vital because they needed to be as light and strong as possible, and at the same time they had move the air as fast as possible. They were all solvable problems, mathematically, but it was an awful lot of work to do it. “He told me later that the whole project was based on whether a computer could do Fourier transforms at least as fast as three engineers with slide rules. He found that not only could it do that, but it could also do Laplace transforms. That was his summary of the business case.” As well as setting out the business case for purchasing a computer, including savings, growth potential and a ten-fold efficiency improvement, the report also looked at the potential impact on Rolls-Royce’s internal politics – how it would be received by the engineers, the accountancy department and so on. Tim adds: “You can see him picking his way through the politics of it all to come to the conclusion that it can be good for everybody. It also shows what a democratic company Rolls-Royce was. It certainly wasn’t a company where the boss said we’re going to do this, and everybody goes and does it. It was definitely a place where different parties could each make their case and negotiate.” The report also looks at alternative computer suppliers. The options were between renting an IBM machine (a 602A made and supported in the UK) and Vickers Powers-Samas, made and supported in France. The project was successfully implemented following the report and Rolls-Royce became one of the pioneers of early computing in aerospace and engineering in general. Tim says: “Although my father played a key role in that, and his understanding of the politics was quite an important part of it, computers didn’t suit him. He preferred hydraulics, something he could feel and see and push around.” Age 4, Tim started going to Stanley House School in Derby, a private school. He says: “My parents were a strange mixture, they were pretty left wing, they were fellow travellers, communists almost. My father knew members of the group which became known as the Cambridge Spies at university.. They were all a few years ahead of him, but his politics were definitely left-wing, and he met my mother through that connection. On the other hand, my parents evidently didn’t want to send me to the local state school, they put me in a private school right across the other side of town.” Tim found that school a lonely experience. He stayed there for three years before moving to the county primary school in 1949, after the family moved to Allestree, then a village outside Derby. The change of school saw Tim flourish and pass his Eleven Plus exam, as did more than 30 other children from the school that year. “Allestree County Primary contributed to the abolition of the Eleven Plus by showing almost every child could pass it with the right training,” he says. Tim also gained a scholarship to Abbotsholme, a private school, and started there in 1953.. He says of the experience: “It was not a particularly good school educationally. It was a good place for doing your own thing and getting out in the country. The headmaster had been a Himalayan climber before the war and led school climbing expeditions which I am still grateful for.” Tim also ran the school’s printing press, he says: “It meant typesetting, editing and proofreading, running the thing physically, and getting a crew together. You needed two or three people to make it work at any decent speed. It was all very manual, pushing and shoving.” Tim gained several O levels including additional maths, physics, chemistry, biology, before opting for physics, maths and chemistry at A level. In 1960 he went to Imperial College to study physics. He says: “I liked London, I wanted to be in London, that was the main reason for going there, rather than trying to go to Oxford or Cambridge. Somebody who’d known my parents, as part of the left-wing networks from the thirties, turned out to be a lecturer at Imperial College, and came and gave a talk at school and encouraged me to go there.” Of his first use of a computer, Tim says: “I first got a computer in the early eighties, an Apple 2e. My first problem was how to switch it on.” While at university, Tim decided he wanted to be a science journalist. He says: “My father was one of the first subscribers to the New Scientist, so I was reading that and quite alert to the potential of science writing. I worked on the university newspaper called Sennet. I did a lot of student journalism for a year or two and from that I started writing paid for pieces for a long dead economics magazine called The Statist, which was a rather feeble rival to The Economist. They paid me for writing pieces about the space launches. … I decided I wanted to be a science journalist, and I was pushing at an open door, frankly, by comparison with what young people have to do today to get decent jobs. I got good advice from people like John Maddox, who was a distinguished science writer.” In 1963, Tim was offered a job with the BBC but opted instead to join the Daily Telegraph because it paid more. He became assistant science writer to Anthony Smith, the Daily Telegraph’s science correspondent who was taking some time out to fly balloons in East Africa. Tim says: “I was sitting there with nobody to guide me, but the phone was ringing with people who wanted the Daily Telegraph to come to a press conference here and press conference there, so while I didn’t get the ideal training, I got a lot of good exposure.” Against the background of the Harold Wilson’s white heat of technology speech, Tim wrote a piece on automation. He says: “I think in those days actually automation was more a daydream than the reality. The things that were actually automated were automated to quite a limited extent. In the sixties if you wanted to automate something, you didn’t use electronics, you used hydraulics, but you could see the electronics coming down the line.” After a year at the Daily Telegraph, Tim became science correspondent with The Statist, the publication he’d been writing for since at university, including an article on ‘how computers work’. Written while he was still at the Daily Telegraph. He says; “I wasn’t supposed to freelance so Patrick Skilton was the author of that article, it was a play on my wife’s name; she was born Patricia Skilton.” After a year with The Statist, Tim joined the Illustrated London News, which he describes as good fun, he adds: “From the 1840s to the early 20th century, it was the leading pictorial magazine.” He goes on to describe how it became almost frozen in the Edwardian period.. But then it was bought by the Thomson organisation and their idea was to transform it into something to compete with Life, Paris Match etc. Tim Green was the editor and he hired me as a science correspondent. I was doing a lot of space stories, every other week we’d get some spectacular photographs which were a delight to use.” Tim says of his movement through several roles: “I moved because I got offered jobs. The Telegraph was great, but I was just a junior and I had not been properly trained. To be a journalist, you’re advised to work in the provinces, learn shorthand and get properly trained. I’d skipped that and so I wasn’t getting it quite right. The Statist gave me a bit more scope, but it was quite a limited magazine. Illustrated London News was great. I could do all sorts of things, I was with people my own age, or not much older, and that gave me an education and allowed me to write the kind of articles which The Sunday Times wanted. I didn’t go asking for any of these jobs. It was just the natural thing to do”. Towards the end of his time with the Illustrated London News, overlapping with the Sunday Times, Tim presented a six programme series for the BBC called The New Electronics. He says of the experience: “It was very educational for me about the very early days of integrated circuits, the idea that you could get more than one transistor on a chip, etc.” In 1967 Tim joined the Sunday Times as technology correspondent, The paper, run by Harold Evans, was renowned for producing revelatory scoops such as its exposure of the thalidomide scandal. Tim says: “It was very open, it was an excellent place to work. A lot of what I was writing about was computing, computer applications and silicon chips and what they did. About half of my output at least was electronics, digital type things.” One example was on the concept of packet switching after an interview with Donald Davies at the National Physical Laboratory. “They were talking about this thing called packet switching which, some years later, turned out to be something called the internet. I did a Sunday Times piece about how Britain could have a digital communications network.” One formative experience was a major press trip run by IBM to the USA and Canada. “The comparison with what I had seen in doing The New Electronics series was very significant,” he says. “I saw how limited and naïve British attempts were at developing the electronics industry. For example, Ferranti were making chips in a converted old cotton mill when we know that the whole environment has got to be absolutely sterile. It was not realised quite how sterile, but everybody knew that you didn’t use an old building; you were tying your hands behind your back before you started.” Picking out one of his most prominent stories, he says it came from researching what the space programme meant for transfer of technology. “I went to California and I visited the place where they built the return landing module and they put me in the a training version of it. I was able to see the control board and all the switches what they did. We had a NASA publication which had a big diagram of it as well. So when Apollo returned from the moon, we ran a story on the module splashing down into the sea, it was a whole page in The Sunday Times with just the control panel, the instructions and how they landed. It wasn’t carefully planned or anything, it just happened. That was great.” In the Autumn of 1970, Tim left the Sunday Times to edit a new publication, Engineering Now. The magazine ran to just six issues and then, despite being well received by its readers, had to fold. Tim says: “The business model didn’t work and there was a recession coming on. The venture capitalists who were backing it, had managed to do it purely on borrowed money as far as I could see, and they were stopping funding because it was just not reaching its advertising target. I think it could have worked given a year’s support and money in good times, but one of the problems was that the reach of the adverts just wasn’t big enough. We were sending the paper out to about 90,000 engineers, but the ads were aiming at much narrower groups such as just structural or just electronic engineers.” After Engineering Now, Tim changed roles and left journalism. He says: “I stopped being a journalist. I’ve been looking at my cuttings again and thinking, maybe I shouldn’t have stopped, because I think I was quite good. Somebody once asked me, “Why did you stop? You were a brilliant journalist.” But they didn’t tell me that at the time.” Instead, Tim together with David Fishlock, then science editor at the Financial Times, co-founded Ovum Ltd. This was a long-discussed idea to do in-depth research about new developments in technology and publish it at a premium price. Tim explains: “The first one we did was Video Cassettes 1971, and that went pretty well, though we sold it for a cheap price. The thing that really showed it worked were the ones we published for the Electrical Research Association about the work they had done on microprocessors. Four transistors on a chip was the standard in the first one we did, and by the next one it was eight on a chip. That was a bestseller and I can remember having a holiday in France and feeling really quite comfortable financially, thanks to the ERA’s reports. But bestsellers come and go, that’s the problem.” Another successful one was on packet switching which Tim wrote, he adds: “It was one of the more important ones that I did. Looking back, it was about the prehistory of the internet, as it moved from a huge military project into commercial application.” Tim also wrote a book in this period, Network Communities: the Computer in our Lives, published by Weidenfeld & Nicholson in 1971. Drawing on three years of Sunday Times reporting, It covered the emergent commercial applications of online computing – such as airline bookings, banking, social applications, information retrieval and computer access. It was an important source for later work with Logica and Ovum. Tim continued working with Ovum for four years and decided, after a bout of depression, to move on. His next role saw him join Logica as a consultant in October 1975. Founded by Philip Hughes and Len Taylor in 1969 the company was already making a name as a leader in the application of mini-computers. Tim joined its Management Consulting Group run by David Sayers. The group produced reports on wide-ranging topics, from public lending rights to satellites for data communications. Tim says: “Logica had got the contract for SWIFTNet and were building all these networks around the world. However, they found it very difficult to get all the details they needed about telecommunications cost in different countries,and particularly on what leased circuits cost.. My first job was to produce a study on tariffs for all the different communication services across all the countries of Western Europe. That’s what I spent 1976 doing, it was very well regarded at the time, it was fairly definitive compilation of all the tariffs of 17 countries. BT people told me later that they used it as their source for what the BT tariffs were.” After this project, Logica was invited to bid for the Eurodata ’78 project. This was run by the Eurodata Foundation, which Tim describes as “a club of PTTs”. He explains: “They wanted a study of data communications across all their territories, more or less the whole of Western Europe. I was part of the team preparing the bid and I developed a methodology for how we would do the forecasts required. It was based on identifying the applications for data communications and forecasting the demand for them. We went to a bidders’ meeting in the historic Telefonica building in Madrid and the PTT representatives asked us’ ‘How would your methodology forecast the volume of data traffic between Berlin and Munich.’ We had the answer and I was told afterwards we were the only bidder which had an answer. So we got the job.” “I think this study provided the first definitive picture of the status of data communications across Europe,” says Tim. “I want to revisit it and see if I can assemble and publish some of the main results for their historical value.” In 1982, having left Logica, Tim re-formed Ovum Limited. To start with he was on his own with invaluable part-time help from Denise Him. However, he was approached by a few of his ex-colleagues from Logica who wanted to join him. They bought into Ovum. Tim says: “The key thing was that I was happy to part with having a majority of the company. I wouldn’t be controlling the company and that was one of the better decisions I ever made because they went on and made a marvellous job of it.” He adds: “My period with Ovum 2 was 1982 to 1985.. Then in 1985, Ron Sasson, David Lewin, Richard Kee and Julian Hewett joined. I remained as a consultant and director until 1990 and then it was clear that I was not actually in practice contributing all that much. I decided to slip away before I was pushed.” Having produced reports on fax machines and packet switching technologies, Tim says that there were some interesting attitudes from the telecommunications to the new technologies. On fax machines, he says: “BT saw it as a nuisance; it locks up the telephone line for a long time, there’s lots of Erlangs in it, it jams up the exchanges. There was general reluctance to expedite new technology by the established telecoms companies. … Across the whole of Europe there was definitely an attitude that it works this way, we understand this way, people coming along with new-fangled digital ideas and whatnot are going to tip over the apple cart, we ought to try and stick with what we know. It was quite repressive.” On packet switching on the other side of the Atlantic, he says: “The resistance in America was a rather different kind, because the Bell companies were all very jealous of their territory, all very jealous of their rights to carry communications, determined to block other enterprises from investing in this area and providing rival services and so on. So the causes of the conservatism, the roots were probably the same, but the apparent causes were different. The telcos were dragging their feet about the whole thing and instead of what might have been an opportunity to become the leading big technology companies that we see today, they completely lost out on it.” In 1991, Tim launched Look Multimedia to make films and videos to meet the demand for new media of the time. He says: “It was a version of the doing something in-depth which would meet business needs and this time it was in-depth with video on the topics of new technology in computers, it turned out to be software technology mostly. We did one on the internet which was quite good and got an award.” During this time, Tim describes himself as almost semi-retired, he explains: “It didn’t take an awful lot of my time really, because Keith Hocking, who was selling the video contracts, did a very good job, and, I didn’t make the films. I was in charge of the scripts and the content of it, overall strategy etc, but I spent a lot of time walking and went on some quite long holidays. It was a different time for me; I wasn’t really engaged with it.” In 1998, Tim, with the backing of two other colleagues he had met while working at Logica, founded Point Topic. He explains: “Geoff Eagland and George Kessler, were part of the David Sayers Management Consultancy team in Logica. There was an attractive tax scheme for backing new companies at the time, and they had some spare money, so they backed me, which was essential. “In 1998 broadband was clearly getting going and was going to be vital. Geoff and George could see the story, they had a similar background to me, and we started out by basically collecting statistics, more definitive statistics than other people managed, because we were spending more time on it with more expertise. It really grew from that. “We had a tariff service, looking at what the tariffs were for all the broadband suppliers across the world after a few years, and data was used very extensively in cases about should this be as cheap as possible or should it be more expensive. So that built up to a well-known international service. Then we had to move on to broader things, because obviously that became a pretty routine piece of information after a few years. “It was a one-man band initially, but I quickly had people helping me, including John Bosnell, Leila Hackett, and then my son Oliver Johnson, who started around 2004. We built up to about ten people by the time of the financial crash.” The crash impacted the company’s subscribers, Tim continues: “We had several people drop their subscriptions and so on and they were big chunky subscriptions and so we just had to cut back quite severely. But we survived and it’s now running as a profitable company and providing mapping, broadband mapping services.” Tim says that Point Topic made an important step in 2005 when it switched its focus from “producing international statistics, which have a limited market, to actually mapping broadband coverage.” He adds: “The idea was that we should go down to postcode level in the UK and be able to take a database of 1.7 million postcodes and allocate broadband, using various different sources of information, like speed tests and coverage maps and all these things, add them together and really start saying, at the postcode level, who was offering broadband, what was the choice, what was the take-up, and producing these massive map databases “We’ve been doing it now for 18 years or so. The new idea is to apply it across Europe as a whole, because while there are excellent take-up maps done by the PTTs, the dominant carriers, and governments, in those countries, they don’t go into the detail that Point Topic provides in the UK. So that’s another turn in Point Topic’s career. Oliver is well in charge now, I’m still a director but my role is minimal. We have a long-term colleague, Jolanta Stanke, who’s a very important part of the team. The team is growing further now, and they’ve incorporated a new company, Expert Intelligence, to offer broadband mapping across Europe. It means creating huge, complex databases which have to be maintained and accessed on a day-to-day basis. “Oliver created something called the European Kilometre Grid (EKG), which maps broadband take-up in kilometer hexagons, you need hexagons to fit onto a spherical world. That level of detail has been available for some time. Point Topic’s been working since 2011 to provide basic mapping for the European Commission of broadband take-up by regions or counties within countries, essential stuff.” Asked if the roll out of broadband in the UK was efficient, Tim says: “You could grumble about it of course, nothing’s perfect, but I don’t think the fact that we didn’t have those flagship very high speed services held the economy back in any real way.” On the subject of cable, Tim adds: “You could say that the American investors generously bought us a fairly comprehensive high-speed cable network. I’ve never looked at it in depth financially, but it’s not clear to me if they’ve ever got their money back or not.” In the lead-up to the year 2000, Tim was doing consultancy with Ovum and together with David Bradshaw worked on a contract with the Cabinet Office. He explains: “The project was to survey what was happening before, be on call on the night in case things fell over at midnight, and then do a survey afterwards about what had happened. There was a lot of fuss and people saying it was all unnecessary, we shouldn’t be bothered with this, but everybody we surveyed after midnight 2000, together with other anecdotal evidence, showed that almost everybody had had something that if they hadn’t been prepared would have caused them a big problem. The whole Y2K thing was much more worthwhile than most people realise today.” Asked about the potential negative impact of artificial intelligence (AI), Tim says, he is not worried about it exactly because it is artificial. He adds: “What people miss is that it’s not live intelligence. AIs don’t have motivation. They don’t know what they’re doing, they don’t know why they’re doing it. But every living thing, even a single-celled amoeba has a really powerful motivation all the time, they have to stay alive. …. So I don’t believe in the idea that an AI would somehow supersede us. What it may do is plug into our brains. The brain interface to AI could obviously be very powerful. But they are subordinate to living things and we’re the top of the pyramid as far as living things are concerned.” Asked about what mistakes he has made, Tim says: “A big mistake was missing the onset of the internet in the early 1990s. Having really latched on to the pre-history of the internet in the 1970’s and ‘80s, I took my eye off the ball. I should have been really been going along with it instead of catching up with it rather late.” Asked if he considers himself a journalist or a researcher, Tim says: “researcher covers it. It’s a bit like journalism, writing reports and so on, but it’s finding out about things in a broader sense than just journalism. One of the problems with journalism is you’re always trying to make a good story, so you make it more black and white, you may have to kowtow to what various people think you should be writing, you’re not actually at the academic end of the thing which is what is the actual verifiable situation. I think that’s one major reason why I’d stopped being a journalist because I really did want to write things which were the whole truth, rather than just a short excerpt.” Interviewed by Richard Sharpe Transcribed by Susan Nicholls Abstracted by Lynda Feeley