Find out about a new podcast on the history of women working in computing in our guest blog by science writer Georgina Ferry

I love the way an archive can set you off on a journey to quite unexpected places. A file I opened nearly 30 years ago jolted me out of a molecular biology furrow into under-explored corners in the history of IT – niches that I still occupy from time to time. So it was that Tom Abram from AIT heard me speaking about the LEO computer at the Centre for Computing History in Cambridge in May 2023, and asked me to write about my projects.

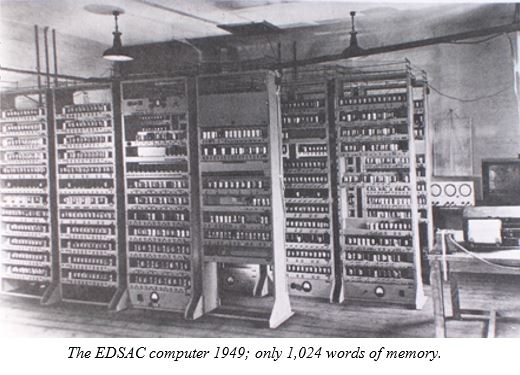

It all started with my biography of the Nobel prizewinning X-ray crystallographer, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin. Hodgkin worked at Oxford University between the 1930s and the 1970s, a period during which digital computing transformed her subject. In the mid-1950s Oxford had no computing service, while Cambridge had built the EDSAC and crystallographers had used it to solve the first protein structures.

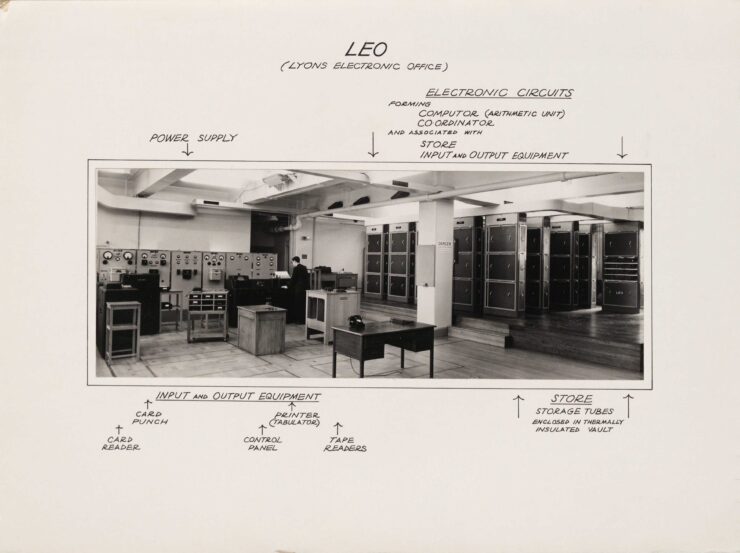

Hodgkin was asked to chair a committee to explore what computers were available and choose one to purchase. One of those they considered, described in two closely-typed sheets of foolscap that I found among the committee’s archived papers, was the LEO II, offered for sale by Leo Computers Ltd, a subsidiary of the caterers J Lyons & Co.

I was astonished to learn that Lyons had built the first computer to run a business application, and thought the story ought to be more widely known. I quickly wrote a proposal for a short, accessible account of the computer’s hopeful rise and sad demise, which was accepted by the publisher Fourth Estate. A Computer Called LEO came out in 2003, and was selected as a Radio 4 Book of the Week.

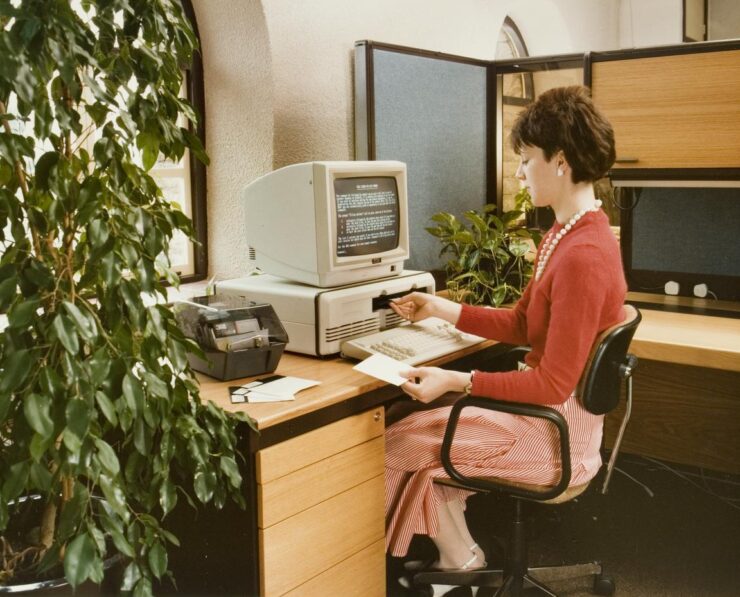

My dabbling in computer history combined with my interest in women scientists brought me to the attention of Professor Ursula Martin of the Department of Computing Science at Oxford. The department, and a separate University IT Services, had both grown out of the original Computing Laboratory launched in 1957 with the purchase not of a LEO but of a Ferranti Mercury, which finally arrived two years later. Planning for the lab stipulated that it should employ ‘a suitable number of non-graduate (girl) computers’.

Ursula wanted to track down some of these ‘girls’, as well as other women who played pioneering roles in the laboratory. She used some funding from a previous history of computing grant to employ me to collect oral history interviews from 14 of these women. The interviews are available as podcasts, and summarised in an article I wrote for Mathematics Today.

I have no background in computing, and were it not for those faded foolscap sheets I would not be writing this. It is no surprise that I am a passionate supporter of the need to preserve archives that are treasure troves of human endeavour.