By Richard Sharpe

October 2022

Kathleen Booth (nee Britten) died late last month at the age of 100 following a remarkable series of pioneering contributions to the development of IT. Here are just seven things she achieved:

- wrote the first assembler programme, bootstrapping software development up from machine code in binary to simple logical instructions;

- wrote a natural language translation program in the mid-1950s translating from French into English;

- wrote one of the first books on programming: Programming for an Automatic Digital Computer (1958);

- co-founded with her husband Andrew Booth what became known as the School of Computer Science and Information Systems at Birkbeck College – see more here;

- taught some of the first courses in computer science in any university;

- helped devise the first rotating storage device attached to a computer; and

- wrote the software for a series of small computers designed by her husband.

She also, at the age of 70, co-authored a paper on the use of neural networks with her son.

Andrew Booth had spent six months in the USA studying Von Neumann’s ideas on computer architectures in 1947. He returned to London and devised the Automatic Relay Computer. Kathleen did the programming.

In 1949 Booth moved into valves and built a Simple Electronic Computer then the All-purpose Electronic Rayon Computer (APERC) sponsored by the British Rayon Corporation. (Simon Lavington Early British Computers, Manchester University Press 1980 p62-63). Kathleen did the programming for all. They were small, cheap for the day and needed no air conditioning. One of them, the APERC, was used by the British Tabulating Machine Company as the basis for its 1200 range of computers of which about 100 were sold worldwide at about £25,000 each.

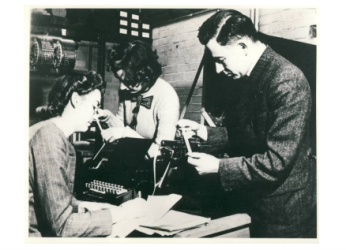

Kathleen Booth (then Britten) , Xenia Sweeting and Andrew Booth working on the ARC in 1946

Sadly, we at Archives of IT did not manage to capture either Kathleen’s nor Andrew’s contributions to the development of IT in the UK. They moved to Canada in the early 1960s. But their influence is felt in the contributions we have captured. Birkbeck College has an annual lecture named after them and Dame Steve Shirley, who completed her PhD at Birkbeck in the 1950s, recalled in 2017 working with Andrew on speech recognition here.

Dr Roger Johnson worked directly with the Booths at Birkbeck. His is a rich memorial to both Kathleen and Andrew. Among other things he told the Archives the story of the Booth multiplier, an essential part of today’s processors.

“Booth needed a hardware multiplier for his machine, and he went out one afternoon with Kathleen, and they went to a tea shop in Southampton Row in Bloomsbury in London, and, an idea came to him, which he says he drew on the back of a paper napkin. And, this was a multiplier, a quite simple multiplier, but nonetheless a very neat multiplier. And this is, this was the first Booth multiplier, and the Booth multiplier has a minor adjustment which a colleague of Booth’s proposed, and hence it’s officially a modified Booth multiplier. The modified Booth multiplier is what is in almost every chip that is being manufactured today. The multiplier is a Booth multiplier. Not many people know this, not many people even need to know it. But nonetheless, the Booth multiplier is one of two ways of doing hardware multiplication, and by far the most popular. So literally, every year billions of these are produced because, these days, as everybody listening to this will know, chips don’t have a single multiplier; they will have many multipliers on circuits across the chips, and, they are Booth multipliers, and they started in a tea shop in Southampton Row in London in, around 1949, 1950.”

Sometimes the influences were indirect. Professor John Tucker was at Bristol University where he was supervised by John Cleave:

John Cleave “had got into logic because, as a young man, he had educated himself and got a PhD from Andrew Booth, the Booths at Birkbeck College. And he did his PhD on machine translation and natural language processing for Booth. And he was very interested in that… and as he had got more and more deeply involved in some of these questions for Booth, he’d become more restless about the foundations of this new thing called computing. And he had stumbled across this thing called logic through his interest in natural languages and suddenly, started to move rapidly in the direction of being a professional mathematical logician.

“So, by the time he [Cleave] was at Bristol, he was a reader with this long experience of early computing through Birkbeck, because remember, he was self-taught, so, Birkbeck, this is typically, a place where all kinds of magic happens to people, er, whose lives are not made into straightforward railroad into university from school.”

During their time at Birkbeck the operation led by the Booths was very small: often only the two of them. Their achievements are, therefore, all the more remarkable.