By Richard Sharpe

March 2023

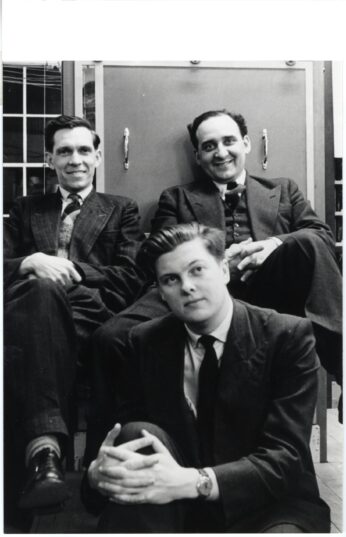

He joined as the third member of the Leo team in 1949 as a senior design engineer. Lyons was attracted to the 25-year old because of his experience in radar in Bomber Command in WWII. He worked on airborne systems for navigational aids. On being demobbed he took night courses in electronics and management.

He worked closely with John Pinkerton and Ernest Lenaerts, he said in his contribution to LEO Remembered, edited by Hilary Caminer and Lisa-Jane McGerty. Shaw tested the units of Leo before they were assembled. “I found out that Wayne Kerr, the company employed to build these units, built them in such a way that although the wiring was all laid out very neatly and tidily it didn’t work properly. This was because the capacitance of the leads running along each other and along metal altered the actual ability to transfer pulses and keep their shape. As a result I was involved in telling them how to rebuild this, or rewire it in the best possible way to minimise this problem. And of course the units began to work better and as a result of that we got the whole unit together and eventually the whole system was beginning to work.”

By then the team had grown to nine, all at Cadby Hall in west London. On the 22nd January 1951 the LEO printed off its first set of maths, according to the diary of David Caminer, responsible for programming and systems specifications for LEO (Caminer and McGerty p20). By February 9th the payroll programme was completed and first ran live on the 15th for the weekly payroll run on the Thursday and payment to the employees on Friday.

The designers of LEO had economised as much as possible so as to fit within the capital budget of £100,000, Shaw told LEO Remembered: “I personally think they economised too much in the sense of not giving the valves sufficient air conditioning. This made things more difficult because circuits in those days were very susceptible to changes in temperature.”

LEO I was up and running so design started on LEO II. Shaw’s role was to help design the memory. “By overlapping the pulses in the delay line [of mercury tubes] it was possible to have storage access times four times faster for LEO II than for LEO I so that the processor didn’t have to wait so long, providing a much faster machine without a major processor redesign.”

Shaw decided to up sticks and emigrate to Australia in 1956: he ended up at the University Sydney. There he developed magnetic tape backing store for the University’s SILLIAC computer, a derivative of the University of Illinois’ ILLIAC. (Bird, Leo the first business computer Hasler, 1994 p209)

Shaw returned to the UK in 1960 and joined English Electric, helping the design the KDF9. This was, for its time, a large scale high speed computer using transistors. It was probably the first zero-address computer which processed Reverse Polish notation, of considerable assistance to compiler writers. (Lavington, Early British Computers Manchester University Press 1980, p76) This design also enhanced performance as the processor did not have to access the main store as many times as the conventional designs. When English Electric took over Leo Computers in 1963 to form EELC Shaw found himself working again with Pinkerton.

ICL was formed with the merger of ICT and EELC in 1968 and Shaw followed into the ICL fold.

The Times reports that at the end of his life he lived in clutter surrounded by computer and history journals. But the garden was immaculate as was he when attending Leo Computer Society meetings, “with jacket, tie and brown and white correspondence shoes.”