This month Archives of IT has been taking part on social media in Cybersecurity Awareness Month, an annual global initiative to raise awareness and educate the public about cyber security. It was established in 2004 by the National Cybersecurity Alliance and the US Department of Homeland Security to raise awareness and educate individuals and organisation on how to protect themselves. Since then other regions, countries and organisations have got behind the initiative such as the EU, UK and NHS.

We’ve been looking at insights from experts interviewed by AIT and here we give an overview of the cyber security industry and how these experts have made an impact over the past two decades.

Fastest growing tech occupation in the UK

Cyber security is the fastest growing tech occupation in the UK and according to data from the Office of National Statistics the number of people working in cyber roles has more than doubled (128%) between 2021 and 2024. However, there is a severe skills gap with an acute lack of cyber security professionals to meet the growing threats. A recent report by cyber security firm, Socura says there is just one cyber security professional for every 86 companies.

This is despite there being an estimated 14.8 cyberattacks against UK businesses every minute. As of January 2024, Statista records that 21% of UK organisations reported a data breach once a month, while 18% reported a data breach once a week.

It’s no surprise then that the global revenue for the cybersecurity market was $83.35bn in 2016 and is projected to reach $185.70bn by the end of the year and up to $271.90bn by 2029 according to Statista.

What is cyber security?

Cybersecurity refers to defences against electronic attacks launched via computer systems and according to the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), established in 2016 as the UK’s national technical authority for cyber threats and Information Assurance, cyber security is the process whereby states, organisations and individuals reduce the risk of cyberattack.

“This is achieved by protecting the devices we use such as smartphones, tablets, laptops and computers, and the services we access – both online and at work – from theft or damage.”

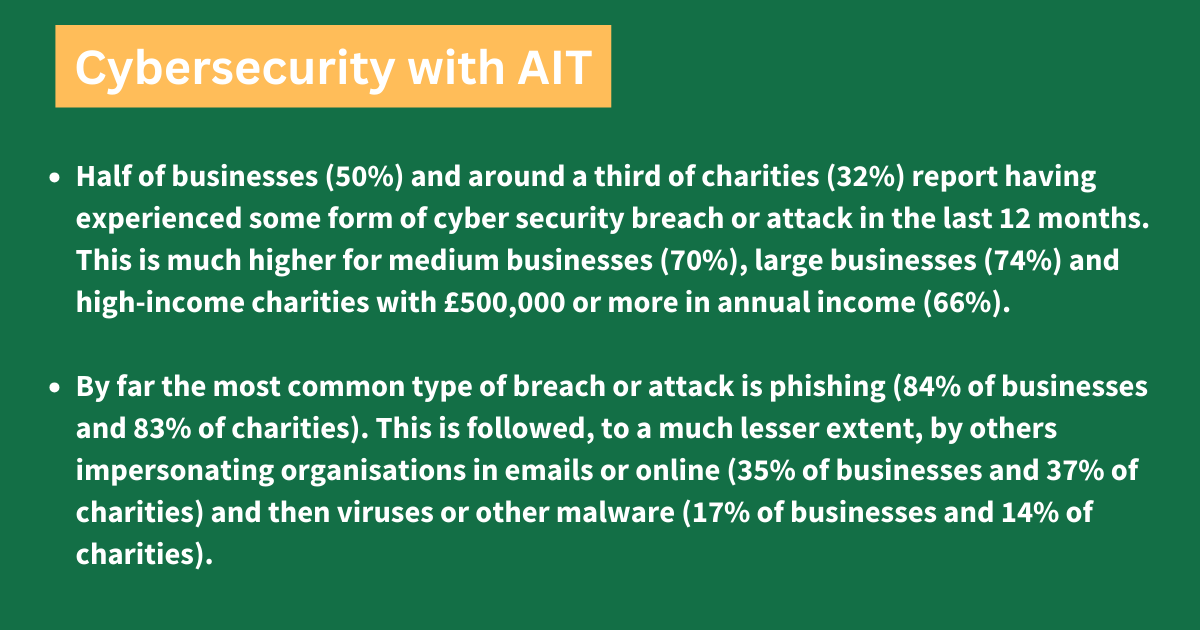

The NCSC’s Cyber Security Breaches Survey – a research study for UK cyber resilience – published on 9 April 2024 (and aligning with the National Cyber Strategy) found that:

Extensive implications

Regardless of the hacker’s age, background, location and motivation, financial or political or simply the challenge, cybercrime has extensive implications.

A headline yesterday (30 October 2024) on the BBC News website ran: Transport for London (TfL) Oyster photocards are still unavailable following a cyber attack.

The report went on to say: “About 5,000 customers were contacted by TfL saying details including their sort codes and bank account numbers could have been accessed by hackers amid the “cyber security incident” at the start of September. A 17-year-old boy was arrested over the hack, which also included names, emails, home addresses and Oyster refund data.”

They can shut down or seriously affect healthcare services, for example, the Cyber Security Breaches Survey stated that as a result of the ransomware attack affecting the NHS in England in June, more than 10,000 outpatient appointments and 1,693 elective procedures were postponed across King’s College Hospital, and Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital. The total cost of cyber attacks to the UK was estimated at £27 billion per annum in 2011 and this figure is likely to have increased.

They can also have huge financial implications with the British Library losing an estimated £1.6m due to the cyber attack that took place in October last year, and will have to invest further funds to renew its IT infrastructure.

And they can also play their part in cyber espionage and warfare for example in the Stuxnet attack on Iran uncovered in 2010, which was a malicious computer worm, caused substantial damage to its nuclear programme and was thought to have been developed by the US and Israel.

Crossing the Rubicon

Chris Hurst, Chief Information Officer and Chief Information Security Officer for cybersecurity innovation company, Blackwired, says in his interview with AIT, along with colleague Iain Johnston, in May 2022, that ‘the Rubicon was crossed’ in cyber security in 2010 when the US defined cyber attacks against states as the fifth domain of war.

It followed a cultural shift in the first decade of the 21st century where terrorism used new technologies such as computers and networks as both tools and targets for exploitation. The Pentagon established the US Cyber Command in 2010 to defend the military’s networks and attack other countries’ systems. And in In 2011, The White House published an “International Strategy for Cyberspace” that reserved the right to use military force in response to a cyberattack.

“What’s generally attacked from the dark space and by bad actors is the systems and processes of management control. The three things that are attacked are production, distribution and exchange, i.e. Banks, Stock Exchanges and so forth,” says Hurst. “The Rubicon was crossed in August 2010 and the Pentagon declared that there was a fifth domain of war [along with land, sea, air and space] and that was cyber.”

Dawn of cyber security

Things have certainly come a long way since the dawn of cyber security in the 1970s when researcher and computer scientist, Bob Thomas, regarded as the father of the industry, created the first computer virus called Creeper in 1971 that could move across ARPANET’s network. Thomas designed Creeper specifically to demonstrate the vulnerability of computer systems. Ray Tomlinson, the inventor of email, followed this up by writing the programme Reaper, which chased and deleted Creeper and became possibly the first antivirus software.

Professor Jim Norton talking at the AIT Forum on the Histories of The Internet in January 2024 said: “I was there at the beginning of the packet switching revolution that led to Arpanet and BT’s experimental packet switch service to the internet we know today. We gave little if any consideration to security. We were hell bent on providing the maximum access at interoperability. We certainly paid the price for that, in spam and spoofing. We didn’t fully comprehend what we were unleashing with social networks and social media. Are we about to face exactly the same challenges with generative machine learning tools such as ChatGPT and Bard?”

AI and Machine learning

Professor Ross Anderson was a Professor of Security Engineering at Cambridge and Edinburgh Universities and agreed that AI and machine learning are areas to watch. A pioneer in his field, he devoted his career to developing security engineering as a discipline: building systems to remain dependable in the face of malice, error or mischance.

In 1998 he co-wrote with Biham and Lars Knudsen the block cipher Serpent, one of the finalists in the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) competition. He also discovered weaknesses in the FISH cipher and designed the stream cipher Pike.

Professor Anderson, interviewed in March 2024, says that over the next five years we should be looking at how artificial intelligence and machine learning will change the cybersecurity landscape.

“Lots of people are hoping that large language models will make it easier either to do attack or to do defence, and so far, that doesn’t seem to be happening. We’re probably going to see for the most part just incremental changes as AI tools are used as personal productivity assistants by people doing either attack work or defence work. But it’s quite possible that you’ll see something changing radically.

“The best analogy that I can give is ransomware. We did a couple of surveys of the cost of cybercrime, one in 2010 and one in 2017, and the amazing thing was that the pattern of crime hadn’t really changed, despite the fact that people had moved from laptops to phones and that they’d moved from on premises service to the cloud, or that they’d moved to social with everything.

“And so that’s showing you that the patterns of cybercrime are not fundamentally technological, they’re fundamentally to do with the constraints in the surrounding legal and economic system. But the one thing that was changing by 2017 and has really changed since then is ransomware, because the invention of bitcoin meant it was possible to collect ransoms, which hadn’t been possible with any skill beforehand. I think that an awful lot of the growth in the cybersecurity industry over the past few years has been down to the fact that medium-sized firms are now at risk of being hit by serious ransomware attacks and having to shell out tens of millions of dollars, or having the embarrassment of seeing their customer data or their internal emails posted on the internet.

“It is quite possible that some application of machine learning will similarly trigger some radical change in the environment sometime in the next few years. And so, watching out for that, figuring out what it is and what to do about it, will be one of the big research problems in the years immediately ahead.”

Increasing reliance on technology

With our increasing reliance on technology both as individuals and businesses, there is always going to be a significant rise in cyber threats, making cyber security a critical concern for individuals, businesses, and governments. These threats can take many forms, such as viruses, malware, ransomware, phishing attacks, social engineering, hacking, and denial-of-service attacks. Cybersecurity aims to prevent these threats from causing harm by identifying and addressing vulnerabilities in computer systems and networks.

To tackle this the first UK Cyber Security Strategy (CSS) was produced by the government in June 2009. It stressed the need for “a coherent approach to cyber security”, with the government, industry, the public and international partners sharing responsibility.

Following the CSS, two new bodies were formed with responsibility for developing a coordinated approach to tackling cyber security. These were The Office of Cyber Security, which became the Office of Cyber Security and Information Assurance (OCSIA) in 2010 and coordinates cyber security programmes run by the UK government including allocation of the National Cyber Security Programme funding. This was followed by the Cyber Security Operations Centre housed within GCHQ with responsibility for providing analysis and overarching situational awareness of cyber threats.

Top priority for national security

Cyber security was one of four top priorities for UK national security in the 2010 National Security Strategy. And in 2011 Dr Andrew Rogoyski, Director of Innovation and Partnerships at the Surrey Institute for People-Centred AI, joined Roke, a research and innovation centre, and was seconded into the Cabinet Office for 18 months from Aug 2012 – Dec 2013 to work with the OCSIA. While there, Dr Rogoyski authored the first UK cyber export strategy and contributed to new export controls for cyber.

“We had serious ministerial support and an international profile,” he says. “It was a good example of good Government policy-making that got cybersecurity as an emerging problem, and saw the importance of things like international leadership, the importance of making different Government departments aware. It wasn’t just GCHQ and the CESG banging the drum about it. It applied to everything from tax to healthcare, and I think made a difference.”

Between 2011 and 2016, the Government funded a National Cyber Security Programme of £860 million to deliver the 2011 National Cyber Security Strategy. The Programme aimed to: Tackle cyber crime and make the UK one of the most secure places in the world to do business in cyberspace.

“I was directly involved in a number of different initiatives, and I ended up writing the UK strategy for cyber export, because we decided that the UK was quite good at this stuff, and that we ought to be exporting our expertise across the world, and the ministers at the time were very keen on progressing this as a thread for economic growth.”

New software strategies

World-renowned expert in software engineering and cybersecurity, Martyn Thomas CBE says that we need to get strategies in place to ensure new software doesn’t contain exploitable defects. If we can’t, we’ll be unable to create the benefits that society demands from the increased use of new technologies.

From 2015 – 2018, Martyn was the Inaugural Livery Company Professor of Information Technology at Gresham College. Martyn has delivered 19 lectures in the past three years under the title ‘Living in a Cyber-Enabled World’.

You can view Martyn’s lectures for Gresham by visiting his Gresham College Page.

“The thread that ran through all the lectures was that we do live in a digital society, in a world that has been empowered and created to a large extent by the developments that have spun out of the invention of modern computing,” he says.

“We need to take advantage of the enormous opportunities that we’ve got, from autonomy, from robotics, from artificial intelligence, and from software engineering, to make the world a better, more prosperous and a more secure place to live in.”

Martyn thinks that the big challenge is going to be exploiting the enormous opportunities that exist, particularly with artificial intelligence and autonomous systems of various sorts, in a way that is robust against the now really threatening cyber environment, the offensive cyber-attacks.

“The work, the strategies that exist, the recommendations that are put forward at the moment, are reactive. They are an attempt to try to minimise the consequences of the defects that exist in the software, rather than looking to the future and saying, how can we replace the software with software that does not contain exploitable defects, and how can we make sure that new software that is being put into critical areas doesn’t contain exploitable defects?

“There’s no strategy to do that, yet, and, and no real commercial motivation for commercial companies to do it, because they don’t carry the consequences of, their customers being cyber attacked, or of systems failing and causing societal damage through cyber-attacks.

“If we can’t solve those problems, we will run into difficulties where we can’t take the benefits that society demands from the increased use of these technologies.”

Education and cross-community cooperation

Sir Edmund Burton, a retired general with extensive experience within the UK defence and security community, was interviewed by AIT in 2019 and said he believed the UK must concentrate on delivering the objectives set out in the UK Cybersecurity Strategies, in particular, concentrating on achieving a real improvement in the coverage and quality of the provision of cybersecurity education and training. He also said the UK’s ICT infrastructures’ interdependency requires cross-community cooperation.

In 2007, Sir Edmund was invited to relieve Baroness Neville-Jones as chairman of the Information Assurance Advisory Council (IAAC). A unique not-for-profit organisation, IAAC brings together a community of 600 or so professionals to address information assurance and related challenges and opportunities faced by the information society.

“It was originally set up in 1999 and since then it has been at the leading edge of many of the developments in AI and cyber security thinking in the UK, maintaining a non-partisan position on matters affecting the way society uses and protects information.” Significantly, IAAC has enabled the creation of an extended ‘Community of Interest’, bringing together academics, government and private sector leaders in order to facilitate the continuous exchange of knowledge, the development of a cyber/information assurance profession and the alignment of what is taught with what is needed; an ongoing challenge for the academic and training communities in consultation with UK employers in the public and private sectors.

Six key areas

IAAC focuses on six key areas including education and research themes such as the implications of cloud and mobile device standards and the need for revision, the issue of identity assurance, organising against cybercrime, addressing the risks and opportunities of social networking and social behaviour, looking at the impact between the citizen and the Internet of Things, and the development of the information assurance and cyber profession.

In 2007/8 three government departments (DWP, HMRC and MOD) incurred major data losses. The Cabinet Office tasked prompt reviews, which were collated into a single Cabinet Office data handling review – the Hannigan Report. Sir Edmund was invited by the Secretary of State for Defence and the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Defence in January 2008 to undertake the review of the circumstances that led to the MOD loss of the data and to consider a broader MoD approach to data protection.

The detailed terms of reference for the review and report were to establish the exact circumstances and events that led to the loss by MoD of personal data. To examine the adequacy of the steps taken to prevent any recurrence and of MoD policy, practice and management arrangements in respect of the protection of personal data more generally, to make recommendations and to report to the MoD’s Permanent Secretary not later than the 30 April 2008.

The Burton Report was published in two parts with an executive summary. The first part set out events leading to the loss of data on 9 January 2008, covering issues relating to the Training, Administration and Financial Management Information System (TAFMIS) and the related policies and procedures. The second part addresses the broader MoD approach to personal data protection.

Enhancing skills

While Sir Edmund believes that prediction is an uncertain business, he envisages “an increasing emphasis and resources being given to addressing ICT and cybersecurity understanding and enhancing skills, both for the benefit of society and to meet the needs of employers across the public and private sectors.” He says: “Legislation and regulation continue to lag technological advances. The gap may narrow, but will continue to be a concern. The ethical issues arising from ICT innovation are not being addressed with sufficient vigour or rigour. Users of ICT systems and services are being presented with flawed software. This is unacceptable. Legislation and regulation have addressed this issue in the hardware domain: increasing attention must be given by private sector providers, and by customers to insistence on trustworthy software.”

Since his interview there the National Cyber Strategy 2022 echoes Sir Edmund’s thoughts and as the UK’s overarching cyber policy it is takeing a “whole-of-society” approach. The strategy has five pillars, including strengthening the UK cyber ecosystem, building a resilient digital UK, and taking the lead in technologies vital to cyber power.

UK in premier cyber league

Dr Robert (Bob) Nowill has had a career as an IT security expert at the Government Communications Head Quarters (GCHQ) and at BT. He now works to try to bridge the skills gap between the pool of talent available to combat cyber security issues and the need for more expertise to achieve higher security

On the subject of the UK’s capabilities to defend itself from the growing threats of cyber warfare, he says: “If you are placing a league table of competence in cyber, whether it’s offensive or defensive, the UK would be in the premier league. We are as well placed as we can be to both respond to and keep up with those threats and opportunities. Having the right calibre of workforce engaged with HMG and others in dealing with the threat and the opportunity is massively important. We know there is a great shortage of people with the right level of skills in cyber, and trying to deal with that is one of the challenges of the day.”

To meet this challenge Dr Nowill chairs the board at the Cyber Security Challenge, which aims to recruit people into the profession. “It’s aimed at people who have never thought of it as a career path in the first place.”

AIT 2025 Forum

Book tickets to AIT’s 2025 Forum on Norms for the Digital Age from Students to States taking place at the Livery Hall of the Worshipful Company of Information Technologists and online – Tuesday 28 January 2025 – where we will explore the Evoluation of Norms, Professionalism and Journalism in the Digital Age, Norms for Students in the Digital Age and Shaping the Application of UN Cyber Norms.

More features from AIT

Iconic Companies: the highs and lows of the UK’s groundbreaking computer industry

How IT is benefitting society in diverse Ways

From bricks to bendables: 40 years of Mobile Phones

Stories of the Internet from the pioneers who made it happen

75 Years of Human-Computer Interaction and its Impact on Society

Supercomputers and the Met Office: at the forefront of weather and climate science

Eight thought leaders give their views on where AI is taking us