By Adrian Murphy – 17 April 2024

It’s been 40 years since the first mobile phones went on sale in the UK and the first networks to support them were built, and in the words of Ben Wood, founder of the Mobile Phone Museum and Chief Analyst at CCS Insight: “No other invention in recent memory has shaped how we live more fundamentally than the mobile phone.”

The development and growth of ever more powerful, flexible and reliable mobile phones – a pocket computer, communications device and video/camera in a single handset – is a fascinating one and is as much about the phones as it is the infrastructure and software.

The first generation of cellular networks were known as 1G and since 2019 5G networks have begun to be deployed worldwide. The first generation (1984) supported analogue voice transmissions, the second (1991) added digital talk and text, the third (2003), data services and the fourth (2012) high-speed internet access. The fifth generation now aims to consolidate these to provide ultra-fast, ultra-reliable, mobile connectivity able to support ever larger data requirements.

And the figures are staggering: today 98% of the UK population has a mobile phone, which we touch on average 2,000 times a day, and German data-gathering platform, Statista estimated in 2022 that telecoms operators across the country generated £12.9bn in mobile retail revenue.

And in the same year worldwide, the International Telecommunications Union estimated there were 8.58bn mobile phone subscriptions from a population of 7.95bn and more than 60% of website traffic now comes from mobile devices up from 6.1% in 2011.

And as we’ll illustrate below, while the development of mobile phones has seemingly been meteoric it has also been an evolutionary process, with each mobile generation introducing improvements in quality, design and functionality.

The first cellular system to support mobile phones

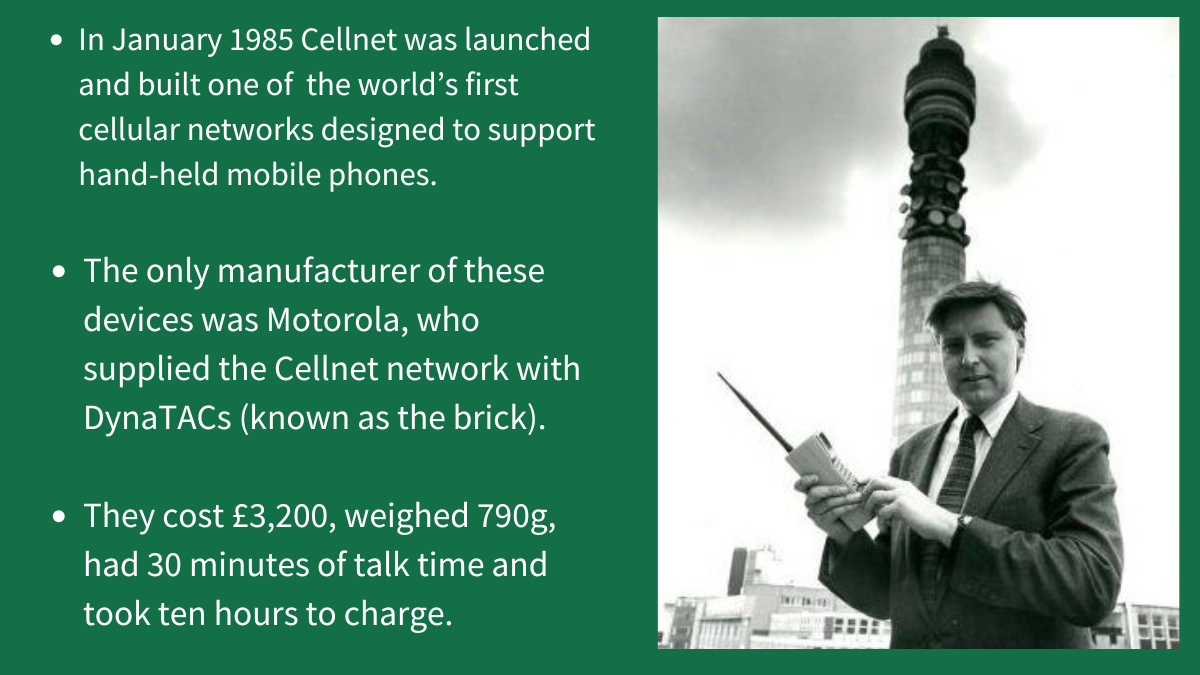

In the summer of 1984, BT’s mobile arm Cellnet (a 60-40 partnership with Securicor and the forerunner to today’s O2) accepted a call from the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) to create a working cellular system that covered central London and a route down to Gatwick Airport as part of the G7 summit. A total of five radio sites (cells) were built, providing some level of coverage from Gatwick and Heathrow airports to Central London, where a site was installed in the BT Tower.

The signalling between network and mobile phone operated to the US AMPS specification although utilising the frequencies allocated by the Total Access Communication System (TACS) in the UK. And by December 1984 (a month before it officially launched) Cellnet had an extensive network in London, designed by director of radio, Dr Mo Ibrahim – which its founding Managing Director, John Carrington, says was the first in the world designed to support handheld mobile phones.

It allowed Cellnet to ‘vigorously test the new technology’ and prepare the infrastructure for the first mobile calls. “We were asked by the DTI after we got the licence if we would put up a small system before we were allowed to start commercially, which was going to be 1st of January 1985, to satisfy the communications requirements of [world leaders] who were meeting in London,” says Carrington, who was interviewed by AIT in September 2016.

“And either courageously or stupidly, I said we’d do this – the competition said they wouldn’t – but it taught us a lot. We put up a system of five cells but it was a working cellular system and Motorola, who were our supplier, put out all the stops to make this work.”

Carrington points to three crucial elements that led to the technology being established by Cellnet. “First, that BT, while being one of the largest major projects in the country, had no idea how to do this in a commercial environment. We had to build hundreds of cells, optimise them and turn them on and we didn’t have the expertise.” As a result, Cellnet brought in WS Atkins, experts in building nuclear power stations and motorways, to build an effective system.

“The second was that for the first time we had working handsets, which we were able to show to customers. And everyone I went out and demonstrated this to wanted one. And that confirmed in my mind that all the doom and gloom merchants and the talk of Big Brother, remember this was 1984, were wrong. I then went back to the shareholders and said we need more money to build a bigger system.

Third was awareness of the demand, good promotion and sales. “We realised this was something that was going to be important and not just car born. We got the extra money and I got our agency (I nearly got fired for this) to do an advert for the first time because I’d just chosen and got approved the name Cellnet. The full page advertisement in the FT showed Ronald Reagan on a mobile telephone in the back of a car [with a caption] saying ‘when you’re out of the office, it needn’t be the end of the world.’

And from that ad we got [up to] 20,000 responses [people filling out coupons from the ad].”

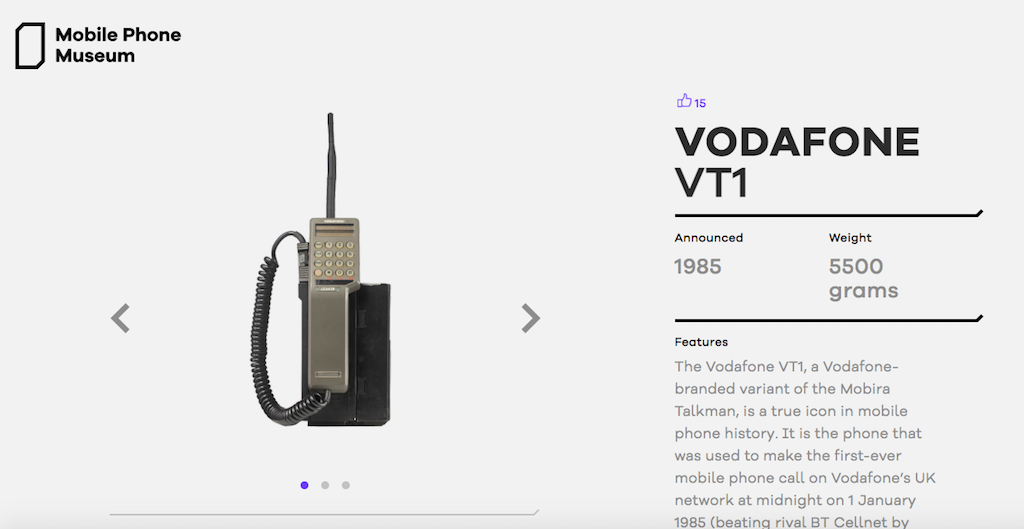

However, there were two cellular networks operating commercially from 1 January 1985 and it was Cellnet’s competitor, Vodafone, that made the first mobile call in the UK.

The first mobile phone call in the UK – 1985

On 1 January 1985 the UK’s first mobile phone call was made on the newly-launched Racal Vodafone (now Vodafone) network. Michael Harrison, the son of former Vodafone Chairman Sir Ernest Harrison, was the first to test the system. He used the Vodafone VT1, a Vodafone-branded variant of the Mobira Talkman, to make the call at midnight on 1 January 1985 (beating Cellnet by nine days).

“We weren’t the first away because I wanted to be absolutely satisfied with the network, which in hindsight I regret now, but one has to move on,” said Carrington.

Despite this, Cellnet had negotiated with 40 organisations to sell cellular phones onto its network and Carrington said he used to look at the numbers every night because at the time the service providers would telext in or fax in the units they had sold for Cellnet to put onto the switch. “After three weeks I didn’t bother because they were coming in in their hundreds and I could see we were on to a winner and we then had to focus on capacity.”

Cellnet used the Motorola DynaTac 8000X – the infamous ‘brick phone’ of the 1980s. It weighed a 790g, had 30 minutes of talk time and took ten hours to charge the battery. And the price in 1985 for one of these early mobile phones was £1,650. Because of this it was out of reach of most people and so mobile phones took some years to really make a difference to society and people’s everyday lives. However, they became a must-have status symbol for wealthy financiers and entrepreneurs and Carrington was convinced they would catch on.

And he was right. According to the BT annual report 1997, by the end of March 1996 Cellnet had 2.4 million customers and the number was rising by about three per cent each month.

How did we get here?

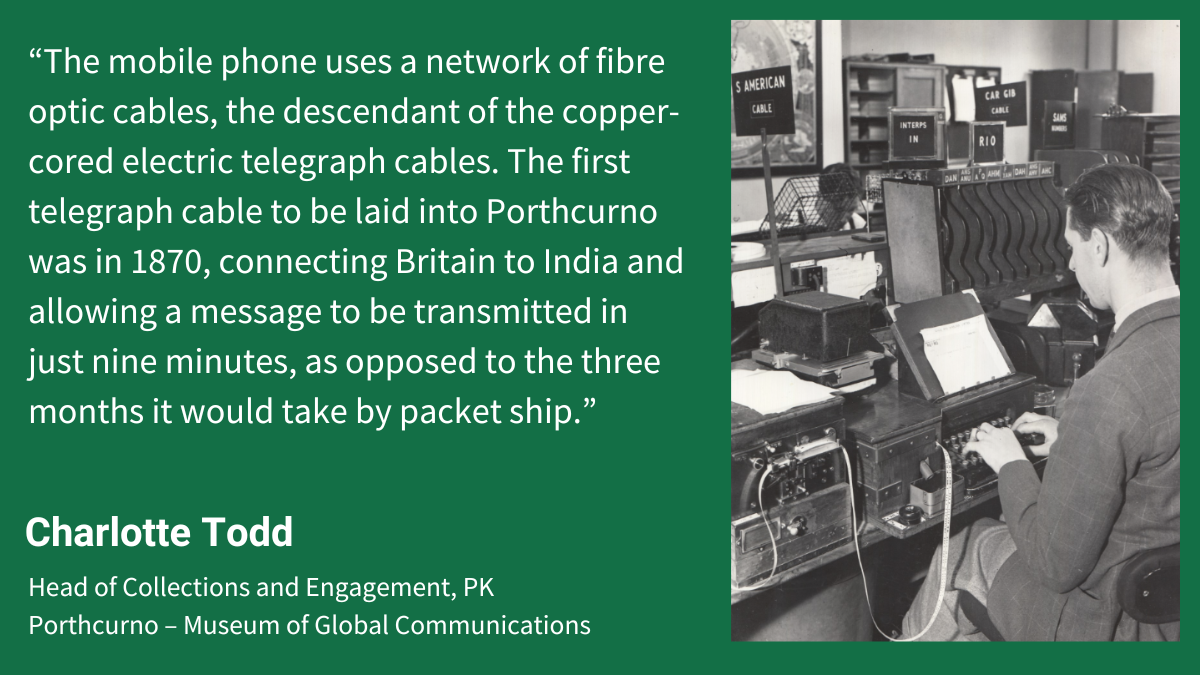

The story of the mobile phone is the continuation of the history of human communication that goes back to the telegraph. At the Going Mobile Exhibition, which is currently running at the Museum of Global Communication and is a collaboration with the Mobile Phone Museum both the early days of telegraph communication and its links to the key developments of mobile phones are covered.

The exhibition traces the development of mobile phone communications and its roots in the history of cable and wireless technology, dating back to the 1840s with the coastal Cornish village of Porthcurno establishing itself as the centre of international telecommunications and once boasting the largest telegraph station in the world.

“The mobile phone uses a network of fibre optic cables, the descendant of the copper-cored electric telegraph cables,” says Charlotte Todd, Head of Collections and Engagement, PK Porthcurno – Museum of Global Communications.

“The first telegraph cable to be laid into Porthcurno was in 1870, connecting Britain to India and allowing a message to be transmitted in just nine minutes, as opposed to the three months it would take by packet ship.”

A patent for a wireless telephone was registered in Kentucky, USA, in 1908 but it wasn’t until the 1940s that engineers from AT&T developed cells for mobile phone base stations and in 1946 the first calls were made on a car radiotelephone in Chicago. This use of cells (areas mapped out on a grid) led to the US referring to today’s devices as cell phones, as opposed to the UK’s preference of mobile phones, the latter of which better describes its capabilities.

Two-way radiophones had been helping police and military personnel to stay in contact since before the Second World War. But these small, private networks required bulky equipment and were inaccessible to the public.

In the UK BT Group as it is now known became the monopoly telecoms supplier when the General Post Office took over the National Telephone Company in 1912 (it has its origins in the Electric Telegraph Company founded in 1846 making it the world’s oldest communications company) and becoming British Telecom in 1980. BT launched the earliest mobile phone service, System 1 from 1959, which was a public radiophone service featuring car phones covering South Lancashire with a powerful central transmitter and receiver situated in Manchester.

The first mobile call

The first-ever mobile phone call was made on 3 April 1973, by Motorola engineer Marty Cooper, while standing on the corner of Sixth Avenue in New York City. He rang a rival at Bell Laboratories, who had been endeavouring to build a car-based mobile phone, to triumphantly tell him that he was calling from ‘a personal, handheld, portable cell phone’.

Cooper said the inspiration for a mobile phone came from the 1950s TV character, Dick Tracy who had a wrist phone, and his goal was to create: “The idea that the phone s an extension of the person. Something that would represent an individual, so you could assign a number not to a place, not to a desk, not to a home, but to a person”.

A version of Cooper’s ground-breaking prototype mobile phone would eventually go on sale to the public as the Motorola DynaTac (dynamic total area coverage) 8000X – the phone that Cellnet had first used for its trials and launch. It weighed 790g, had 30 minutes of talk time and took 10 hours to charge the battery.

According to Professor Hannah Fry on her BBC series, The Secrets of Modern Life: Smartphone episode: “The challenge of the time was packing the days’ massive radio tech into something you could carry. They needed to miniaturize a complicated bit of tech called a duplexer, which allows you to transmit and receive on one antenna simultaneously.”

The first public service for a mobile telephone was in Japan in 1979, which was followed by the introduction of the Nordic Mobile Telephone in 1981 initially between Sweden and Norway and in Denmark and Finland the following year.

In 1983 the first commercial services were introduced by Motorola in the USA. Then, as we’ve mentioned, in the UK in 1985 with Vodafone and Cellnet. The latter resulted in the Conservative government at the time breaking BT’s monopoly on telecommunications with its privatisation and the granting of a licence to Mercury Communications in 1982.

In the same year the government went ahead with plans for a new mobile phone service and licensed two companies, Cellnet and Vodafone, to operate the UK’s first cellular phone networks. In the US, it was a similar story in one way, with the government wanting a break from the dominance of AT&T. However, rather than have a select few network contracts it offered contracts to two companies in every city, which resulted in a series of incompatible networks.

Analogue to digital and GSM

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw a huge expansion of the cellular network due to the conversion from analogue to digital and an increase in customers through pay-as-you-go. By 1996 16 per cent of households in the UK had a mobile phone. New handsets were continually being designed to meet the demand and the latest technologies such as texting. As well as this, in 1996 Vodafone launched Vodafone Prepaid the first pay-as-you-go, non-contract phone service.

Another major development that facilitated this growth was the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), which was a set of protocols for the second generation of cellular networks. In 1991 the GSM mobile network standard was finalised, and the Radiolinja network in Finland became the first.

The GSM network technology delivered superior audio quality and expanded network capacity compared to the previous 1G Nordic Mobile Telephone and AMPS networks. Dr Mike Short CBE, interviewed by AIT in August 2018, spent 30 years working in mobile communications from 1987 to 2017 and in 1989 became Director of Cellnet.

Dr Short says from 1985 to 1991 the world was operating in an analogue mobile landscape or a first generation (1G) one and the UK was at the forefront of the major developments and had a huge market share.

“If I take the UK market from [that period] the UK was the second largest mobile market in the world, second only to the US. And given that Japan had launched mobile before the UK that was quite remarkable. That’s because we had a very vibrant set of distribution channels with companies such as London Car Telephone and Carphone Warehouse and this retail and wholesale market wasn’t typical in most countries. But most of all by fierce competition which drove innovation and performance. Other European countries tended to have network monopolies in mobile.”

At the time the UK networks included founders Cellnet and Vodafone and emerging new entrants such as Mercury One2one, Unitel and Orange, which subsequently became Everything Everywhere (EE).

Dr Short was part of the launch of GSM in the UK and deeply involved in moving the mobile network from analogue to digital, which he says was a balancing act between capital costs, analogue depreciation and other factors.

“Because we had a successful growth business in analogue cellular having invested a lot in analogue we didn’t want to just jump in until everything was right. Until the handsets were small enough and cheap enough until the analogue network had depreciated in value. We also knew we needed a minimum amount of coverage before we launched. Once you’ve got an established 1G network with significant country coverage, you don’t want to go backwards and launch something new even though it’s digital. If it’s got less coverage, it’s not going to fly quickly.”

In 1991 Mike was nominated as Cellnet representative on GSM Association, working cooperatively on operational standards, and later became Deputy Chairman and in 1995, Chairman, followed by 7 years on its Board. He chaired the first Mobile World Congress in Cannes in February 1996. In 1987 European leaders met in Bonn to sign the agreement that would allow mobile phone users to roam from one country to another, hopping from network to network. Mike signed the first 40 international roaming deals for Cellnet as cross border connectivity grew.

Nokia dominance and the first text messages

Nokia, is one of Finland’s most successful companies and began as a pulp mill in 1865, transferring to mobile telecommunications in the 1990s. Its dominance was fuelled by its ability to adapt to consumer preferences, a vast array of products catering to various market segments and strong partnerships with mobile carriers. In the 1990s, Nokia released more handsets than any of its rivals and in 1998 overtook Motorola to become the best-selling mobile phone brand in the world. At its peak in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company held a 40% global market share, making it the undisputed leader in the industry. During this time one of the most significant breakthroughs in mobile phone technology was the short messaging service or SMS.

World’s first text message

In 1992 the world’s first ever SMS message was sent in the UK by software engineer Neil Papworth, tasked with creating an SMS service for Vodafone. He sent Richard Jarvis, a director at Vodafone a “Merry Christmas” text message.

However, it wasn’t until 1998 that customers could reap the full benefit of the technology. It was through the work of Dr Short who brought the UK operators together to develop workable texting services and helped coin the term itself. He ensured that texts could be sent between as well as within networks and led teaching and awareness campaigns, including “teach your mum to text”. He was also involved in the first trials of mobile internet and mobile TV.

“In the early days of GSM texting hadn’t started yet, it was in the technology but to actually implement it you needed to be able to send text messages from one network to another,” he said. “Initially, texting had different names on the different operating networks. So, I pulled the operators together in 1998, five years after the launch of the GSM networks [in the UK], and said ‘shall we try something different as it’s not working well today?’.

“And we started to say ‘well, yes, let’s call it the same thing. So, instead of calling it SMS [Short Message Service] let’s call it text. And let’s do a cross industry campaign that says this is how you do it. So we teach people to text and we had a campaign, which was called ‘Teach Your Mum to Text’ and we also ensured we sent text messages to each other and when you start to make it available to all and promote it with certain handsets it booms. And it went from 30 million texts in 1998 to a billion in 1999 just in the UK and it peaked at about 150 billion in [2014].”

The larger screens on handsets such as Blackberry made this feasible and Nokia was also making its phones text-friendly.

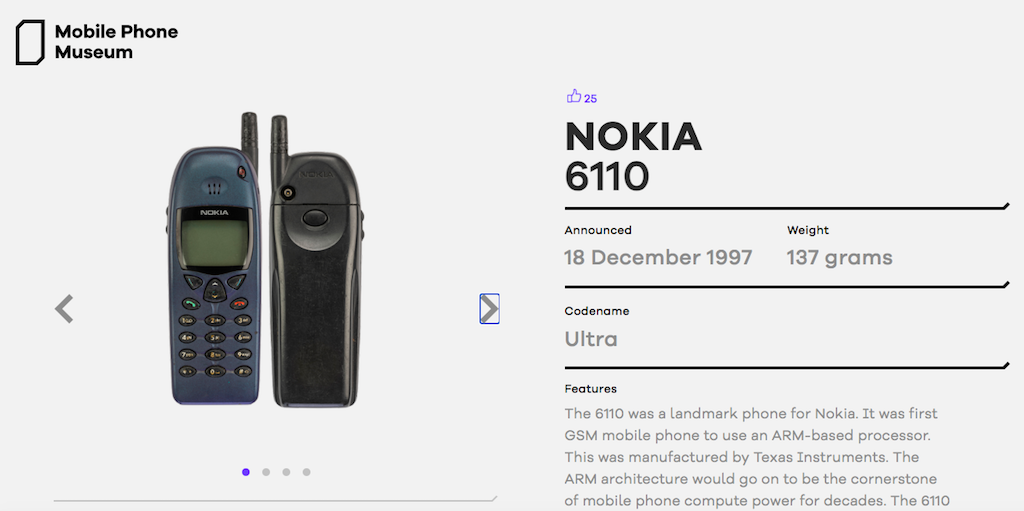

The first GSM phone to use an Arm processor

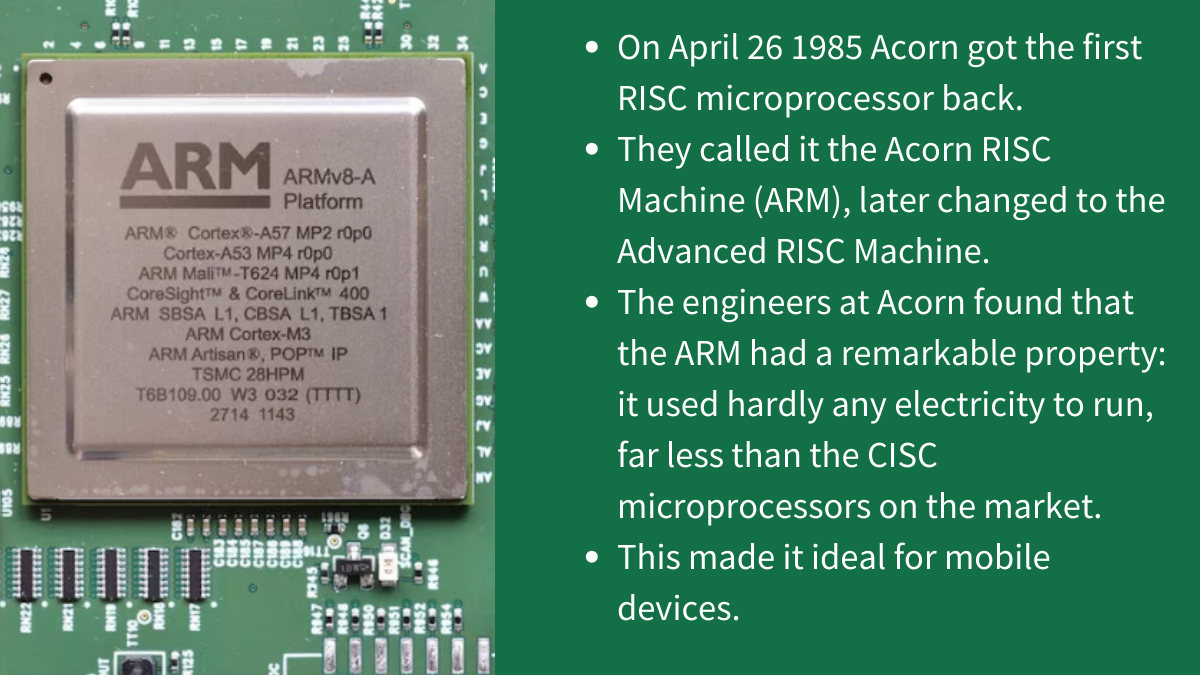

The first mass-market GSM phone was the Nokia 1011 released in 1992 but it was the Nokia 6110 that perhaps has the most significance, at least from a UK perspective. That’s because the Nokia 6110, released in 1997 was the first GSM mobile phone to use a processor made by Arm, a semiconductor and software design company based in Cambridge launched in 1991. Arm chip are now embedded in 99% of smartphones.

British engineer and CEO of Arm at the time, Sir Robin Saxby, interviewed by AIT in 2017, said the Nokia contract was a turning point for the company. “The really successful product that made the headlines was the Nokia 6110 and we particularly designed the thumb architecture to meet the needs of Nokia. When they looked at Arm, they said we love the investment of it, we love the performance but your code density is rubbish. And we said, ‘well, we can fix that’. The code density being rubbish means that in the chip your memory footprint would be too expensive and the phone would be too expensive, so that’s what we had to fix for Nokia.”

Arm processors had low power consumption and high performance

One of the main benefits of Arm architecture for mobile phone design is its low power consumption and high performance. According to Arm their processors are optimised for battery life and thermal management, which are crucial for mobile devices that need to run for long periods of time and avoid overheating.

“They also deliver fast and smooth performance for various tasks, such as web browsing, gaming, video streaming and multitasking. ARM processors also enable more innovation and diversity in mobile phone design, as they allow manufacturers to create different form factors, features, and functionalities for their devices. For example, ARM processors can support foldable phones, dual-screen phones, 5G phones, and edge computing devices.”

And in 1997 this allowed the Nokia 6110 to weigh in at 137g and have a stand by longer than any other cellular phone at the time with a standard battery lasting up to 270 hours.

An advertisement at the time boasted it had: “Excellent audio quality thanks to the new intelligent technology used in the speaker with a large five-line display with dynamic fonts that change size automatically so you can read a five-line message without scrolling.

“The Nokia 6110 series is everything you want in a cellular phone plus a few extras you might not expect like a calendar and a calculator and three games, and you can connect it to a laptop, PC or a printer using the cellular data suite with a built-in infrared link.”

One of the three games featured was Snake, which was a huge success at the time and a turning point for mobile games and is considered the first mobile phone app. However, the first smartphone, the IBM Simon, was released in 1994 and included a few simple apps, such as a calendar, address book, calculator and notepad. And the Hagenuk MT-2000, also launched in 1994 featured Tetris and was possibly the world’s first mobile with a pre-loaded game.

WAP and mobile internet

It was Nokia again that made a significant breakthrough with its 7110 known as being the first WAP (Wireless Application Protocol) phone. It was unveiled at the GSM World Congress in Cannes, France in February 1999. It supported the WAP 1.2 browser WAP, a rudimentary way of connecting to the internet from a mobile phone. At the time, Nokia gave examples, including news, weather reports, stock prices, e-mail, flight schedules and wireless banking and electronic commerce.

Eva Pascoe, an internet entrepreneur and consultant, who was interviewed by AIT in 2019, correctly predicted in 1999 that mobile phones would in the future be used for shopping and browsing on daily commutes.

This included a public exchange with Alan Sugar, who disagreed with her declaring: “If I am in the office, I use my computer, while at home I use my PC. Since most of the time I am in one or other location, there is no need to receive information on a mobile phone.”

She said: “Smartphones [as we recognise them today] started coming up in 2005, but there was a previous technology WAP which was like a pre-smartphone. I was quite convinced early on that mobile phones needed to have data reception, because, we were all commuting, and so we thought that mobile phones will be useful if you can do a bit of browsing, or if you want to pay your bills online.

“WAP was the first wireless platform, but it wasn’t successful. It was superseded by the next generation, but we developed a WAP version for Topshop online and it worked. It was an early start, but it taught us a lot and when we developed Topshop for smartphones, we had a lot of solutions in place, so we were quite early in its development and it was really, really very exciting.”

The iPhone and rival Android

If mobile phones have fundamentally changed the way we live, then the iPhone fundamentally changed the way mobile phones work. Launched in 2007 it brought together much of the developing technology into one device, in what became an ubequitous rectagular design with a large touchscreen that went on to dominate the market.

By 2000 camera phones were available in the shape of the J-Phone, mp3 players had been around since 1997 with Apple launching its iPod in 2001 (able to save 1,000 songs) and web browsing was becoming a more common feature on mobile phones.

What the iPhone did was bring all these features together. This meant in 2007 customers could now make calls, listen to the radio or their favourite saved music, surf the web, send emails and texts, play games, pay bills, use the first Google maps and snap photos. It was a mobile phone revolution and a reinvention just over 20 years into their lifespan and ushered in an era of hyperconnectivity.

Former BBC technology correspondent, Rory Cellan-Jones, interviewed by AIT in 2021, was at the launch on 9 January 2007 at Macworld in San Francisco and says he was sceptical about the event, headed by then Apple CEO, Steve Jobs, as he’d been to so many tech announcements that were more often than not a big disappointment.

“The single most charismatic and amazing performance that I’ve witnessed was Steve Jobs unveiling the iPhone. The performance in the Moscone Theater is just worth looking at again. He walks onto the stage in his trademark black polar neck jumper, wire-framed glasses, jeans and there’s a momentary pause and he looks down as if the sermon is about to begin and then looks up and says ‘we’re going to make a bit of history here today’.

“And then he goes onto outline the recent history of technology, which of course turns out to be all about groundbreaking Apple products. Then going through this mantra: ‘We’re going to unveil not one but three groundbreaking products here today. We’re going to unveil a widescreen iPod with touchscreen controls, an internet device and a mobile phone. A widescreen iPod with touchscreen controls, an internet device and a mobile phone’. And he keeps on doing this, and of course the whole point is they are actually one device: the iPhone. And he whipped the crowd up into a frenzy.”

Apple went onto dominant the smartphone market and became innovators in many aspects including AI with Siri launching in 2011 and FaceID in 2017. The iPhone is Apple’s most valuable product creating 52% of its revenue.

Android

Although since the introduction of the T-Mobile G2 in 2008 Apple has had a serious rival. The G2 was the first production mobile phone to run the Android operating system developed by Google and is used by various mobile phone manufacturers.

Today Android phones, with Samsung the leading manufacturer, make up 70% of all phones bought across the world, while Apple’s iOS-powered iPhones account for 27% (still the most popular handset).

In recent years Apple and Samsung have been vying for top spot for sales of smartphones. Latest figures show global smartphone shipments increased 7.8% to 289.4 million units during January-March, with Samsung taking a 20.8% market share, clinching the top spot from Apple with 17.3% (losing its first position it had at the end of 2023).

Increased data and Binge Packages

With the advance of smartphones such as the iPhone, HTC and Samsung Galaxy coupled with the establishment of apps and social media, phone usage required not only more memory and better battery life but more data.

According to the National Infrastructure Commission 2014 saw total data demand increase by 53 per cent in the UK (per active mobile SIM). “As a result of these advances and the ability for increasingly sophisticated mobile devices to reach a mass market, mobile telecommunications and mobile services more broadly, are now established at the heart of our society and economy.”

Watching videos on mobile phones grew in popularity but the data consumption was something the network providers had to address. Sarah Bond, who was Senior Vice-President of Emerging Businesses at T-Mobile at the time wanted to extend the brand into video, banking and data monetisation services.

This led her to create ‘Binge On’ in 2015 a product innovation that enabled people to truly have unlimited data and continues to this day. With video quality increasing, T-Mobile found that people were consuming huge amounts of data. Sarah, interviewed by AIT in 2019, says: “We were having congestion problems; the network was really under a lot of stress. So, we sat there, and we said, ‘Wait a second. This is video that somebody’s watching on their phone; a tiny little screen where you can’t tell the difference between 1080p and 480p. So, we created a product by which people would opt in to having their video at 480p, and in exchange they could keep unlimited.”

She says it was a big risk. “I remember really clearly, I was driving into the office on a weekend to sit down with the team to go through all of our calculations and how we had laid everything out and I was on the phone with my boss, and he goes, ‘Sarah, you are gambling with the entire business right now. I think I’m going to come in and look at it with you.’ The day we switched it on, we predicted it (network load) would go down by 9.8 per cent, and it actually went down by 10.3. Today, having your video over mobile phones at 480p is pretty much the industry standard, and it’s because of what we created there.”

The legacy and future of mobile phones

Mobile phones have undoubtedly changed the way we connect and live our lives but the hyperconnectivety they provide is both a source for good and bad as they are a trusty companion but can also have health implications to eyes and sleep caused from excess usage as well as detrimental health effects from social media.

Ben Wood, who co-founded the Mobile Phone Museum in 2020, and is chief analyst at CCS Insight, a consultancy focused on connected technology, has been working in the mobile phone industry for almost the entirety of their history, having started out as graduate trainee at Vodafone in 1985.

“I look back at those early days at Vodafone where we were fiddling about with text messaging, where you’d have to push a button three times to get a letter on a screen and send messages to each other. We didn’t really know what we were doing and what a big impact that it would have and it would go on to be billions of messages sent. 1.5 billion mobile phones get sold every year and that’s about 42 phones every second: it’s incredible.”

Ben, interviewed by AIT in 2022, points out that mobile phones have provided: “Education, the ability for people to create commerce, they are an invaluable part of everyday life, it’s the computer in your pocket. Society is hugely dependent on them now, even more so during the pandemic. Look at some of the things we’ve seen such as using QR codes in a restaurant to get a virtual menu, getting a text alert with a confirmation pin code for your bank account, being up to date with current affairs. The rise of citizen journalism where the ubiquitous camera inside a mobile phone, which was considered quite a preposterous idea when it was introduced in Japan, has gone on to record really iconic events.”

Ben also mentions the key role played by mobile phones in pivotal historical moments such as the 7/7 London bombings (7 July 2005),: “It was the first time that we saw live coverage of an incident as it was unfolding. There were people who filmed short videos and took photographs on the tube trains that had been affected, as they left the trains and stumbled down the tunnels to come out. We’d never seen any kind of footage like that in our lives.”

Asked about some of the negative impacts of phones including social media bullying, he says: “We’re very conscious of that. I think that that’s one of the interesting things when I go into schools and I talk to headteachers. Most of the time when they talk about mobile phones in schools it’s largely negative and I’m not going to pretend that there aren’t issues like access to pornography or phones used for bullying and all those sorts of things. “However, there’s plenty of things that they can do as a force for good as well. What the teachers love when we take the phones into the schools is the fact that it is a positive message, in so far as it’s an amazing industry, much of which was pioneered and developed in the UK. It is something that we can be very proud of. It’s a testament to the evolution of technology.”

Challenges

“We’ve seen so many technologies subsumed into the mobile phone, of course, we’ve got challenges as we move into the future as well, around sustainability and telling that story in terms of how we need to think about these devices, we need to start thinking about new areas such as how are they recycled, can we improve their longevity, can we, make them more secure, can we make them repairable? This is part of the story that we’re trying to tell as part of the Mobile Phone Museum charity project.

“User interface is a huge part of the mobile phone, it started primarily as physical buttons and the software and the hardware started to get blended together. Now, we’re moving to all sorts of other things like artificial intelligence, voice interaction, gesture interactions, etc, which will undoubtedly signal where the technology goes in the future.

“Having said that things have been rather dull since Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in January 2007, that moved towards a rectangular monoblock with all phones starting to look the same. However, I’m very excited about moving away from that sea of sameness to a little bit more design diversity with the arrival of flexible display technology, which allows us to have foldable phones and phones with screens wrapped around them. That is starting a whole new chapter of innovation.”

5G and increased societal gains

And while the UK was at the forefront of mobile communications in the 1980s and 1990s, according to the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) it now performs poorly in comparison to other countries when looking at the availability of 4G. With that in mind the NIC, established in 2015, was asked to advise government on the steps the UK should take in order to become a world leader in the deployment of 5G mobile telecommunications network. “Mobile connectivity has become a necessity,” the report said. “The market has driven great advances since the advent of the mobile phone but government must now play an active role to ensure that basic services are available wherever we live, work and travel, and our roads, railways and city centres must be made 5G ready as quickly as possible.”

5G allows even faster connectivity, lower latency connectivity, and according to Ben it will spawn a whole new range of applications that we’ve not previously seen.

“One thing history has shown me is that every time we provide people more bandwidth, [innovators] fill that pipe up and it means we’re going to get richer and more exciting experiences. I think we’ll also start to see mobile technology starting to play a more important role in healthcare and in the health and wellness of our daily lives. We have things like smartwatches, which measure heart rate, sleep, etc, in future, maybe they’ll have blood sugar, which could be a revolutionary step forward for diabetics. Our future technological development is almost limited by our imagination. The sheer volume of mobile phones and the reach of connected technology has made the world smaller, and that is super-exciting and bodes well for even more innovation in the future.”

Related content

Billy D’Arcy, Chief Executive Officer for BAI Communications Group’s UK operation on investing more than £1.2bn over 25 years on mobile networks for the London Underground

Read our article on the Going Mobile exhibition, which inspired this feature. The exhibition is a collaboration between the Mobile Phone Museum and PK Porthcurno – Museum of Global Communication and runs until October 2024

Stories of the Internet from the pioneers who made it happen