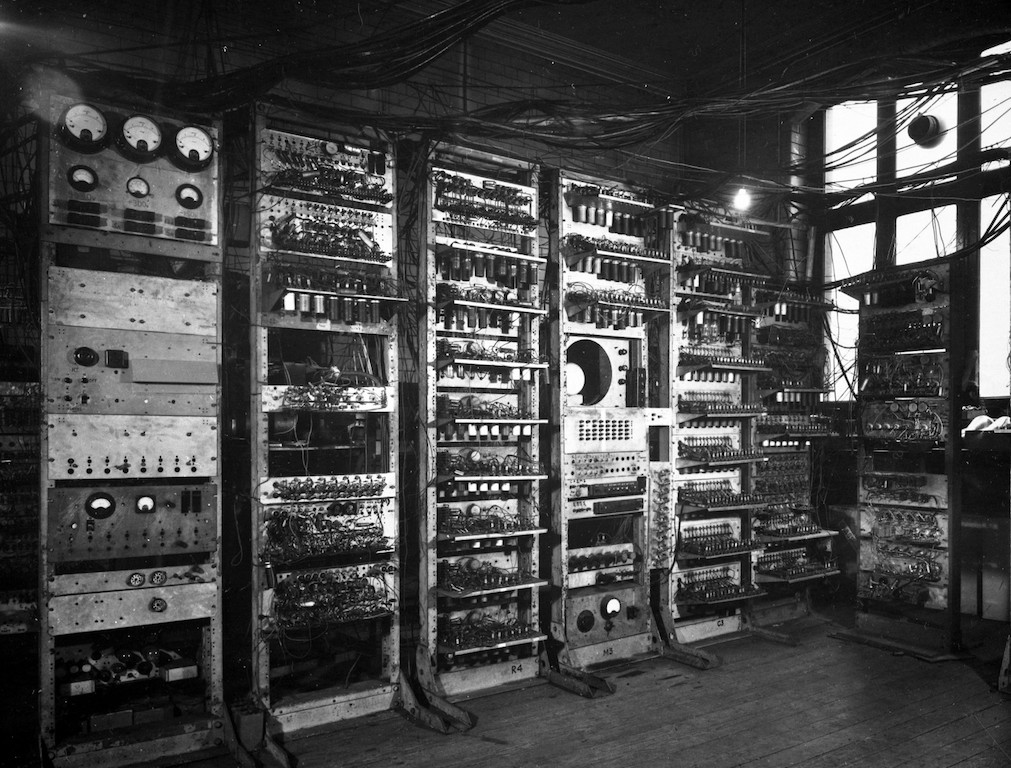

Main image: A LEO II computer which began development in 1954 and was first installed in London by J Lyons & Co in 1957. Photograph courtesy of Professor Frank Land

The UK has produced many successful computer companies, spanning the 1950s to the 1980s, that have blazed a trail for the IT industry not just on these shores but around the world. These companies, small and large, have pioneered new ways of working and living that have become iconic especially household names such as Sinclair with its ZX Spectrum. They are acknowledged for distinctive excellence, highly original and influential and represent particular changes of the time. At Archives of IT (AIT) we have begun a process of compiling biographies of many of these companies and embellishing them with links to our interviewees who have taken active roles in their development.

These include Lyons Electronic Office (LEO), English Electric, Marconi, Ferranti, International Computers Limited (ICL), Acorn Computers and Sinclair Research among others which you can see on our Iconic Companies page.

In this article we have brought together some of our previous observations about how LEO, English Electric, Marconi, Ferranti and ICL were at the forefront of the world’s computer industry and how, through successive mergers, became confused, less effective and finally acquired. We have included personal testomonies as to what it was like working for these companies at the time (and also other observations, see below) from our interviewees and team.

For example, in her interview with AIT in 2017 Dame Stephanie Shirley, information technology pioneer and philanthropist who founded Freelance Programmers in 1962, was asked what she thought of the UK IT industry and she said: “We lost the IT industry a long time ago in this country. The government supported ICL and then it was acquired by Fujitsu and we didn’t have a computer industry anymore. The software companies are doing well, and of course it is the software in the end that is more important, but you’ve got to have both and we have no control over the national hardware.”

Those are fairly strong words but they do reflect a sense of loss common to those information technologists who witnessed the great achievements of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

The Background

Following the Second World War, the UK was at the cutting edge of the computer industry, with Manchester and Cambridge universities competing for the first implementation of a stored program digital computer.

Seventy-six years ago, on Monday 21 June 1948, the first stored program computer in the world, the Manchester Baby, ran its first job. It was an experimental machine built in Manchester by a team lead by Sir FC Williams and Tom Kilburn: its purpose was to test the new Williams tubes developed for random-access storage to replace serial-access delay lines. Nicknamed the “Baby” it had a 32×32 bit word with keyboard input and it ran a 52 minute factoring program.

At this time, catering empire J Lyons & Co’s Systems Researcher, John Simmons sent two of his team out to research the use of computers, both in the UK and US, for the routine task of accounting and discovered the EDSAC at Cambridge University one of the world’s first computers to store its program in memory rather than with hard wiring. Lyons decided to invest £3,000 (£74,000 in today’s money) in EDSAC. And this would lead to the UK achieving another first just two years later with the Lyons Electronic Office (LEO), the world’s first business computer.

AIT Director Tom Abram says: “Clearly the UK was a leader in technical innovation after WW2 and indeed in the application of IT to commerce, with the Lyons Electronic Office. Quite soon it was outgunned by the industrial scale of the US, giving them a leading position in the hardware market but the UK remained a force in the application of technology to business, defence and medicine. For example, Professor Denis Noble’s story of using one of the early British Ferranti machines to explain the human heartbeat and Sir Michael Brady’s achievements, applying AI to diagnostic imaging. World leading ideas in future personal medicine are still being developed now at NIBEC in Belfast.

“The discipline of Systems Integration gave rise to a new generation of companies, The Computing Services Industry, including companies such as Hoskyns, Scicon and Logica, which broke new ground but fell one by one into the hands of overseas owners, whether because of their outstanding success or lumpy performance.”

UK’s first computer company: LEO Computers Ltd

In 1954, with the decision to proceed with its second iteration, LEO II and interest from other commercial companies, Lyons esstablished LEO Computers Ltd. LEO Computers was a predecessor of the British flagship computer manufacturer, ICL, which was launched as a result of Government policy in 1968 with a gene pool including famous names such as GEC, English Electric, Ferranti, Powers Samas and EMI.

However, even before it was born ICL was struggling to compete with overseas competition, most notably IBM. Notwithstanding the dominance of overseas companies like IBM in hardware and Oracle and SAP in software, the UK developed a thriving Computer Services Industry in the 70s and 80s, doing systems integration and business transformation. Richard Holway’s magazine System House (available to view in our archive) observed that in the five years from 1985 to 1990 the 10 British companies leading that field lost the initiative as US and European mainland competition moved in.

The commonly referenced example of a company that bucked the UK 20th-century trend is ARM, whose processors power the mobile world. One of the first customers was Apple Computers swiftly followed by Nokia.

Related content: From Bricks to Bendables: 40 years of mobile phones

From cafes to computers: Lyons Electronic Office

J Lyons & Co was founded in 1884 by Joseph Lyons with a teashop in Piccadilly, London and the business would subsequently grow to 250 locations around the UK at its peak and by 1939 the company employed 30,000 people including 1,500 involved in accounting and statistics required to support the supply chains and logistics. Lyons became firm believers after the Second World War that automation was the answer to running their operation more efficiently.

This innovative thinking championed the understanding that businesses could use computers to their advantage. The Lyons board decided that a computer with more capabilities than the EDSAC should be built at their Cadby Hall Factory in West London, led by electronics engineer John Pinkerton. This would be a brand-new type of machine. While EDSAC was an automated calculator, LEO was an electronic office, automating office processes previously done by administrators. In November 1951 LEO was put to work for the first time on the valuation of output from the Lyons bakeries.

In the same year Frank Bushby and Mavis Hinds of the Met Office started using the LEO1 at Cadby Hall, the first business computer. LEO handled company accounts and logistics but also factored in Met Office weather forecasts to influence the goods carried by their ‘fresh produce’ delivery vans.

Working with the first generation of LEO engineers

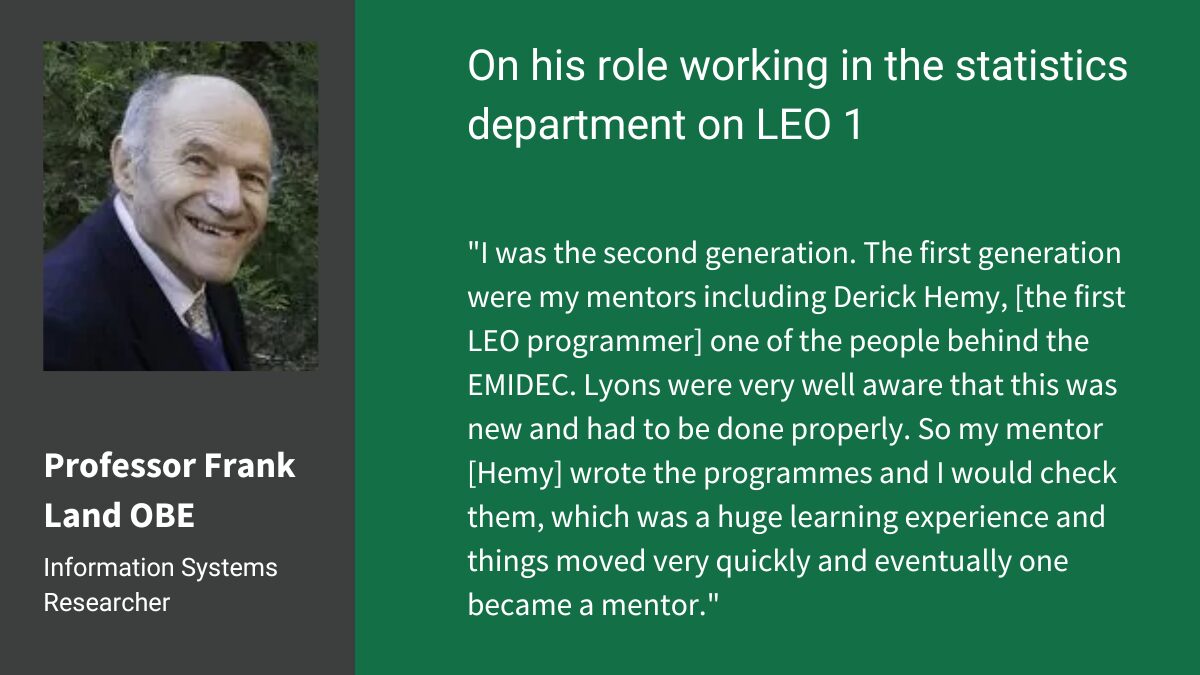

Professor Frank Land OBE, interviewed in May 2018

Professor Frank Land joined in J Lyons & Co in late 1951 (cutting short a PhD to experience the real world), as a clerk in their statistics office. Very early on he says that J Lyons wanted to recruit people from within to join LEO.

“They organised an aptitude test which they called an appreciation course and I found it very tough but with the help of a mathematician friend I managed to struggle through and was taken on to LEO.

Professor Land says that it was no fluke that Lyons had built the world’s first business computer as they had been recruiting high-level people from the 1920s including John Simmons who he says was the epitome of this approach and who came up with the name Lyons Electronic Office.

“He was a first class mathematician from Cambridge, a wrangler. He was taken on with the brief of keeping the business modernised and he reinvented the business. He was innovative and in the 1930s he set up an office called the systems research office, which I don’t think any other business had. And they worked on trying to be as smart as they possible could and he took many of his ideas from Frederick Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management.

Improving efficiency

“He developed new ways of improving the efficiency of the business and providing the management with the kind of information they needed to run the business as speedily as possible. So, Lyons managers got their feedback on what had happened in the week in a white book that was published every Friday and I was part of that system. I was in the statistics office preparing the information that was going into the white book to passed onto the management.

“Lyons had a business which was very smart and had very little fat on it. And they were always looking at ways of reducing that fat. And so in 1947 Simmons sent two of his lieutenants to America to see what new business ideas had cropped up during the war and they saw very little that was better than Lyons did but they discovered [their use of] computers [the American authorities had recently declassified some of the latest technology]. And Ray Thompson had the idea that computers, which were then used purely for technical calculations could solve some of Lyons’s problems such as managing mass data. The old fashioned ways of pen and paper wouldn’t do it and the newer fashion of punch cards was too rigid and computers seemed to bridge that gap.

The first generation of mentors at LEO

“I was part of the second generation at LEO. The first generation were my mentors including Derick Hemy, [the first LEO programmer] one of the people behind the EMIDEC. Lyons were very well aware that this [LEO] was new and had to be done properly. So my mentor [Hemy] wrote the programmes and I would check them, which was a huge learning experience and things moved very quickly and eventually one became a mentor.

Prof Land’s first major management job was taking responsibility for the computer application controlling all the tea that Lyons purchased.

“Lyons had their own tea plantations, bought at tea auctions on Mincing Lane and they had bonded warehouses. LEO had to keep control of each chest of each type of tea, and the tea then had to be blended to taste and cost. The Lyons expert tea tasters had to choose the teas, which the computer could not do, and the computer had to keep track of where all the individual tea chests were, their value, and their movements, from bonded warehouse to factory, to packaging and sales.”

The most influential mentor was David Caminer, who was head of the programming group. “He was the man who invented software engineering and he was very instrumental in making sure we did things right and everything was documented. He was fierce and regarded as a hard boss but offered so much in terms of learning that people appreciated what he did.” (Prof Land would later join up with Caminer to establish The LEO Foundation in 1984 and would write a book with him, John Aris and Peter Hermon entitled LEO: The Incredible Story of the World’s First Business Computer.)

It soon became apparent to the Lyons board that they had created a business computer reliable enough to sell, so they set up a separate company, LEO II in 1961. By 1963 LEO III had arrived and ran on transistors and tape drives instead of mercury valves. The Met Office and Handley Page were some of the companies that bought the technology for their own purposes.

By 1963, however, Lyons was in financial trouble and sold LEO to English Electric. “When we joined English Electric our elders and their very different kind of engineering clashed. We felt that they didn’t have the subtlety and nuance that we had. The important thing for them was to get the sale. To us it was to get the job right. Which is not necessarily a very good business proposition.”

In 1967, Land was selected for a newly established post in what later became the Department of Information Systems at LSE.

The ‘gory’ mergers of LEO with English Electric, Marconi and the formation of ICL

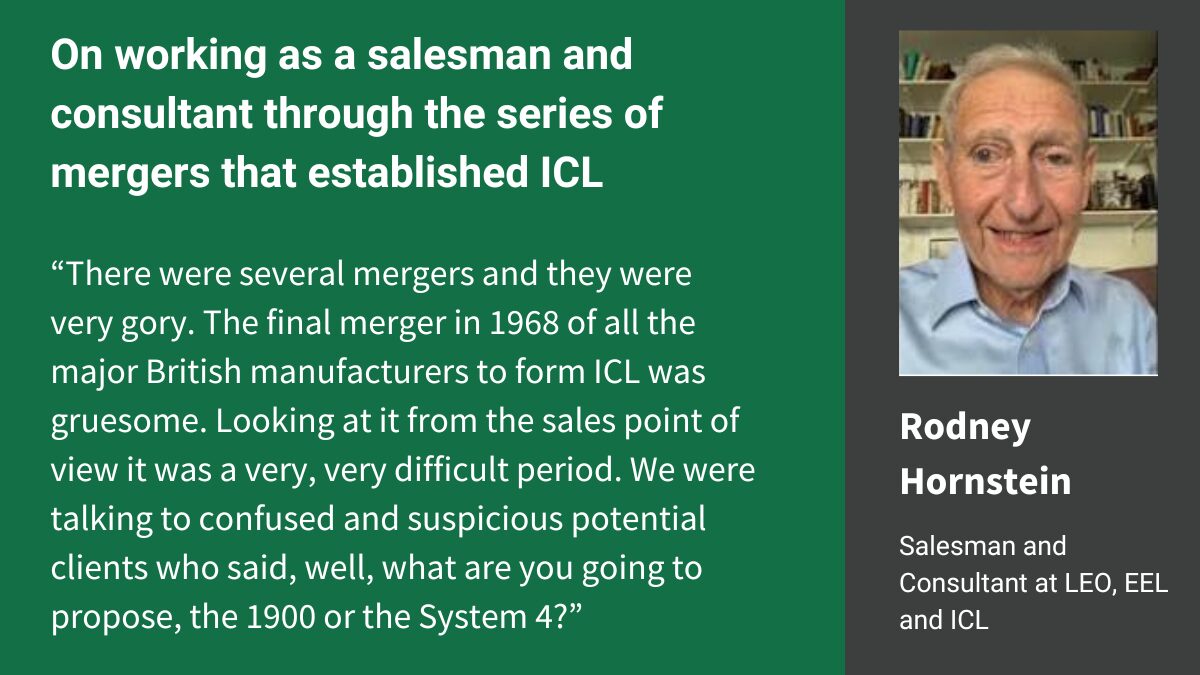

Rodney Hornstein LEO Computers, interviewed in September 2023

Rodney Hornstein joined LEO Computers in 1962 from IBM and would rapidly progress to becoming a salesman, or consultant/programmer as they were called at LEO after being interviewed by Frank Land, subsequently becoming sales manager for English Electric LEO.

Working through the merger of LEO Computers with English Electric to become English Electric LEO, then the addition of Marconi, followed by ICT before finally becoming ICL in 1968, Rodney says: “There were several mergers and they were very gory. The final merger in 1968 of all the major British manufacturers to form ICL was gruesome.

“With each new merger, different and new computers were included in the range, including the LEOs, English Electric’s KDF, System 4 which was RCA designed as compatible to the IBM 360, the ICT 1900 Series and plans for the ICL 2900 series. Looking at it from the sales point of view it was a very, very difficult period. We were talking to confused and suspicious potential clients who said, well, what are you going to propose, the 1900 or the System 4?”

The last LEO III machine ceased to operate in 1981 – it had been producing telephone bills for British Telecom.

English Electric and International Computers Limited (ICL)

English Electric was established in 1918 when five manufacturing companies from the midlands and northwest of the UK merged at the end of the First World War.

They were initially involved with making military, and then civil aviation aircraft, but also made components for trams and electric locomotives including transformers and turbines. In the Second World war they produced the Handley Page bomber and Comet tank and continued to make aircraft for the RAF afterwards, including the jet powered English Electric Canberra and Lightning.

In 1955 English Electric started to make computers. From 1955 they made one of the first commercially available computers called DEUCE (Digital Electronic Universal Computing Engine), a re-engineered version of the National Physical Laboratories Pilot ACE, designed by Alan Turing. Deuce was used in a variety of ways; one client was engine manufacturer Bristol Siddely.

In 1963, LEO Computers Ltd was merged into English Electric Company and this led to the breaking up of the team that had inspired LEO computers.

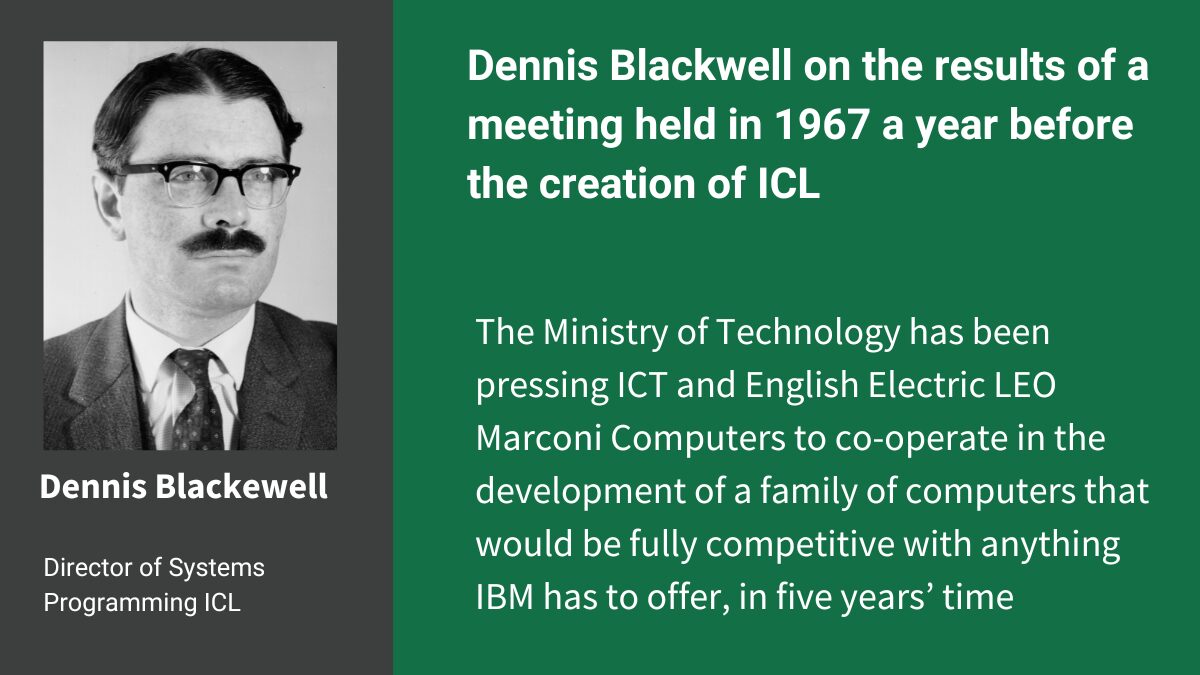

Dennis Blackwell, interviewed by his daughter, Susan, in 2014 and published on AIT in 2023

Dennis Blackwell (1929-2016), was a key figure in the British computer industry for more than 50 years and AIT was given custodianship of his collection – which includes personal correspondence, speeches, company annual reports, publications, reports on various government and industry initiatives and discussions – by his family in 2023.

In January AIT received a Scoping Grant from The National Archives partnership funding programme, Archives Revealed, to utilise the skills of a consultant to help look after the history of the collection and make it available to interested researchers.

Blackwell joined English Electric in 1959 and also worked through the series of mergers to ICL before retiring in 1984. He was instrumental in the creation of ICL by merger of its components, being a member of the Working Party on a New Range of Computing Systems, terms of reference for which are included in his archive.

The next British computer

He was a director of the resulting company in its formative years as Director of Systems Programming, ICL, responsible for addressing issues such as the strategy for “the next British computer” and setting up the ICL “software house” Dataskil. Dennis was also influential in other trade and standards bodies including the British Standards Institute and the British Approvals Board for Telecomms.

He says that by 1968 the British element of the computer industry had amalgamated into two blocks. One was ICT, which included Ferranti and Powers-Samas, and the others were English Electric, LEO, Marconi, and AEI as well as Elliott Automation.

“And government thought that it should try and support a united range which would meet world standards and world markets,” he said.

In his interview Blackwell read from a document, the result of a meeting held between 3-5 July 1967, signed by himself, DJ Blackwell, ACD Hayley, Chief Engineer of English Electric, JMM Pinkerton, LEO Designer, Derek Edridge, Peter Ellis, and George Felton of ICT, which said: “The Ministry of Technology has been pressing ICT and English Electric LEO Marconi Computers to co-operate in the development of a family of computers that would be fully competitive with anything IBM has to offer, in five years’ time.”

Just over a year later ICL was formed on 1 August 1968 and Blackwell says that the whole of the English Electric and LEO Marconi software manufacturing people moved. “In the next two years of course the amalgamating of responsibilities and organising things led to all sorts of [problems]. The normal stresses you have in organisations where one is a much bigger organisation than the other.

Conflicts of interest

“Some chose to leave because they saw better opportunities elsewhere but there were obviously conflicts of interest. Some were eased out because the winning side thought its man was better than the losing side. A number went into the user market place, because there was plenty of interest in having people who are highly competent in the computer world, and some were not appointed in the initial appointments of senior management and therefore effectively made redundant by their original company.

“The accolade was that, English Electric being the smaller party, I would have responsibility for the entire software organisation of both parties. ICT was much larger in its software organisation than English Electric, but technically not as competent. They had less brilliant software developers. Far more machines, far more operators and a lot more programmers who worked on contract for customers. Part of the sales force arrangement. That was before the merger. Their software organisation became under the commercial and marketing side of ICL not the manufacturing side under Echo Organ.

Developing a new range of computers

“The object of the merger was to develop a new range of computers which would take some years to get going and that would require a whole set of consistent software and it was inconceivable that we should continue to produce the languages that existed for high level work on LEO, Ferranti’s Orion, English Electric’s System 4, and ICT’s HEC and ICT’s 1900.

“There weren’t enough people to carry on doing that work, and it would have been absurd. Those people were required to develop the languages for the new range. And so there was no pressing case to continue maintaining those languages and I recommended to Peter Hall, my boss, that we should cease that work. And where necessary tell the customers who were expecting to continue to receive enhancements to existing languages, that those would stop.

“Maintenance of existing software was a major manpower burden on all manufacturers because having issued the software it often had to be maintained and may have had hidden bugs and often needed slightly enhancing because of some changes such as a bigger high-speed memory or the ability to support different peripheral devices from when it was first done.

“So there was always the question of developing going on just like motor cars because we had inherited all the historic British manufacturers’ machines into ICL, there were handfuls of people maintaining what are now known as legacy systems. Old machines that were not being made, manufactured, but were still in use by customers and which required support.

A significant burden

“And this was a very significant past burden if you like, involving all these machines, a whole host of them, from the five or six made by Ferranti, and the five or six made by English Electric and Elliot Automation and AEI.

“The government made it very plain, that as government both in terms of money and no doubt in terms of a purchasing agency, it was interested in there being a strong single British manufacturer which you could rely on. With a single standard.

“Which would make sense and that was undoubtedly one of the thrusting forces on this. And very sensible as well. Especially since IBM had about 70% of the world market, effectively providing a de facto international standard. Very difficult to compete against circumstances like that because IBM was an international company with a presence all over the world, just as ICL in its punched card days had a similar presence, mostly all over the world, but not quite the same.”

ICL Crisis

Anthony Hodson, ICL, interviewed in February 2022

In 1981 trying to develop new, lower end machines in the 2900 range ICL ran into a financial crisis, leading to a takeover bid from Unisys. Despite outstanding financial results in 1979, ICL found itself in trouble following the introduction of the IBM 4300 and the unfavourable turn in exchange rates. By the end of 1981 ICL had racked up a loss of £18.7 million for the year.

In 1979, Anthony Hodson joined ICL in Bracknell as a roving technical consultant working on the X.400 and X.500 which were key parts of the top of the 7 layers of OSI, international standards for open systems interconnection.

At the time Hodson joined ICL, it was a company oriented towards mainframes. “I found it very difficult to understand what was going on in the theoretics of mainframes. This was only mitigated by the fact that on interrogation I found that hardly anybody else really understood what it was all about either. It had got to a rather woolly set of ideas, buzz phrases and things.”

As part of Project Manager Brian Millis’s team, Hodson was involved in the early stages of OSI, which he describes as a foil to IBM and its centralised concept of distributed computing.

ICL had a history of experiencing crises and booms before eventually collapsing and Hodson says that the central issue of the problem was the soaring interest rates of the 1980s which raised the value of the pound and saw ICL’s export market disappear almost overnight.

Huge implosion

“There was a huge implosion, something like 40,000 people were made redundant. The company then went through a very difficult period of rethinking itself. The original board had absolutely no idea what to do next. There was no comfort zone around at the time and there was essentially a collapse. Behind the scenes, I think Maggie Thatcher helped to prop up ICL so that it didn’t completely collapse.

“What was left was the realisation that the small computers with which we had been toying with were now the way the world would develop. So, the culture changed very quickly from very big machines to very small machines and I found myself unusual in being one of the few people that actually worked intensively with very small machines, particularly with the work that I had done with the message switching system which involved really literally low-level programming of the 8086s. X.500 and X.400 seemed particularly important for the rise of electronic mail as a key office application.

Hodson was also involved with word processing and became for a time ICL’s word processing expert. He explains: “I helped them acquire a freestanding word processing system, which they bought from another company.” He was also involved with messaging clients. He adds: “I was involved with ICL’s early days of that, and designed a complete messaging client and implemented it. Having been involved with a number of bids, I saw that ICL’s X.500 work needed a leader, so I did what I could and became that leader.”

Long and difficult struggle

“It was a very long and difficult struggle over the next two years while ICL really decided what they were about. They hadn’t really decided what they were about at the time that I had left in 1993. Were they selling systems solutions to people, or were they selling hardware, or were they selling software, or what? At that time there was a lot of competition in that area, and so it was a big struggle for them.

“They then tied up with Fujitsu who provided the mainframe support base that they had really needed with the demise of all the 2900s etc. Also at the same time there was consulting work which was becoming increasingly important for managing big projects to people, and there was the technology work attempting to do something within the nascent technology such as X.400 messaging and X.500.”

Fujitsu Takeover and the Horizon scandal

In later years, ICL attempted to diversify its product line but it hardware business profits always depended on the mainframe customer base. New ventures included marketing a range of powerful IBM clones made by Fujitsu, various minicomputer and personal computer ranges and (more successfully) a range of retail point-of-sale equipment and back-office software.

In May 1996 ICL Pathway Limited (later Fujitsu Servives) was awarded a government private finance initiative contract to develop an accounting software system known as the Horizon IT system to modernise the Post Office and Benefits Agency the latter of which pulled out in 1999 after delays and setbacks during development.

In 1998 Japanese firm Fujitsu became ICL’s sole shareholder and the ICL brand was dropped in 2002. Between 1999 and 2015 faults in the Horizon system resulted in thousand of innocent subpostmasters pursued for apparant financial shortfalls and more than 900 subpostmasters were convicted of theft, fraud and false accounting. The scandal has been described as the greatest miscarriage of justice in British history and is a sad legacy to the ICL story.

UK succcesses with Micro Computers and microchips

Sinclair Research

One company covered by AIT that really has become iconic, mainly because its computers found their way into millions of homes, is Sinclair Research with its founder Sir Clive Sinclair interviewed by AIT in 2019.

In 1979 Sinclair moved into computers and his breakthrough came with the ZX80, followed closely by the ZX81 and ZX Spectrum. The ZX Spectrum, released in 1982 is one of the UK’s best-selling computers shifting more than five million units.

Sinclair developed the idea for the first home computer under £100 after he watched the joy his son found playing with the Tandy TRS-80. “I saw what computers could do, but they were very expensive. The equivalent to perhaps £2,000 in today’s terms, and I thought, having seen what pleasure they could bring and how readily a youngster could program one, if only we could make one for the right price, which I deemed to be £100 in those days, obviously a lot more today, then it would become something that every man could have.

“The ZX80 used a lot of discrete components and then with the ZX81, I mocked up a lot of the discrete gates into one chip from Ferranti; the entire computer only had four chips in it, at a time when the best competition had 46.”

Acorn computers and the BBC Micro

Chris Curry, who co-founded Acorn Computers, worked for Sir Clive Sinclair on hi-fi systems and helped launch Sinclair’s first calculator. He set up a microprocessor design company with Hermann Hauser and Andy Hopper whose first product was a control processor for a fruit machine.

They decided to build their own microcomputer kits and then a complete system in 1979 which they called Acorn “because it was going to be an expanding and growth-oriented system”.

They were in competition with tens of other start-ups selling microcomputers. In the early 1980s the BBC wanted to run a series of TV programmes to encourage people to take up microcomputers. They were working with an Acorn rival but were not getting very far.

Acorn put together a crash team to design a microcomputer under Steve Furber. They demonstrated the prototype and won the contract which led to 1.5 million shipments, mostly into the education sector. Through this initiative millions learned to programme microcomputers, often developing games, kick-starting the UK computer games industry.

ARM

Arm’s primary business is the design of ARM processors (CPUs) used in virtually all modern smartphones. Its chip design instructions and technologies are used by the world’s largest chip manufacturers such the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and technology giants Apple and Samsung to make their own chips.

The origins of Arm go back to 1983 and Acorn Computers with the acronym originally standing for Acorn RISC Machine. Acorn Computers’ first RISC processor was used in the original Acorn Archimedes and was one of the first RISC processors used in microcomputers.

AIT interviews

Steve Furber principal designer of the Acorn microcomputer and of the BBC Micro and co-designer of the RISC microprocessor at Acorn alongside Sophie Wilson.

Dr Hermann Hauser who he co-founded Acorn with Curry, guided its development including the design of the RISC microprocessor and became a venture capitalist.

Sir Robin Saxby who was the first CEO of Advanced RISC Machines (ARM), the microprocessor company spun out from Acorn in 1991. He started with 12 engineers and helped build the company with his business model to a size where it was worth £23.4 billion in 2016. By August 2023 Arm announced it has filed paperwork to sell its shares in the US and was looking for a valuation of around £47bn.

Quantum Computers and the future

The UK is at the forefront of quantum computing although with stiff competition from the US – with IBM, Google Quantum AI, Amazon, Microsoft and Intel all investing millions – as well as China and the EU.

UK National Quantum Technologies Programme (NQTP) is a £1 billion dynamic collaboration between industry, academia and government. It represents and guides the fission of a leading-edge science into transformative new products and services.

Sir Peter Knight, interviewed by AIT in April 2023, is a British physicist, professor of quantum optics and senior research investigator at Imperial College London, and says we are a decade away from creating a machine of substance.

“If we’re going to build a quantum machine, we’ve got to inhibit this ability to talk to the environment and make it quieter and quieter and that means we have to do much better in terms of the quality of the fabrication of the bits. It wasn’t until about 2015 that we could get that noise level down in such a way that we could be relatively confident we could build a fault-tolerant machine.

“If you look at a classical machine, it’s extraordinarily fault tolerant, you build those error correcting codes in and the ability to actually control what’s going on in a chip on a classical machine is superb. We’re orders of magnitude away from that at the moment in a quantum machine. So the best machine that exists in terms of doing something only has of the order of a hundred fairly noisy qubits at the moment. But our educated guess is that we will have a machine of substance, of consequence within about a decade.”

Milestones

In 2004 the first working pure state NMR quantum computer (based on parahydrogen) was demonstrated at Oxford University, England and University of York. in 2009 Researchers at University of Bristol demonstrate Shor’s algorithm on a silicon photonic chip. In 2018 Oxford researchers successfully use a trapped-ion technique, where they placed two charged atoms in a state of quantum entanglement to speed up logic gates by a factor of 20 to 60 times, as compared with the previous best gates, translated to 1.6 microseconds long, with 99.8% precision.

In February 2024 the UK government announced an investment of £45 million in the UK’s quantum sector – as part of its commitment to transforming into a quantum-enabled economy by 2033 – seizing this technology’s potential to overhaul healthcare, energy, transport and more £30 million investment will go to developing and delivering world-leading prototype quantum computers, providing scientists and engineers with a controlled environment for experimentation.

Quantinuum, formed by the merger of Cambridge Quantum Computing and Honeywell Quantum Solutions, is making huge advances with its H-Series trapped-ion quantum computers setting the highest quantum volume to date of 1,048,576 in April 2024.

Words by Adrian Murphy