ICL (International Computers Limited) existed as a commercial entity and brand from 1968 to 2002; perhaps the flagship computer manufacturer of the UK until it was finally and completely absorbed into its eventual, Japanese owner Fujitsu. The story of ICL illustrates many of the challenges in the UK computer industry over that time, political, technological and commercial. Its roots go back to the days of immediate post-war development of British computer technology as diverse firms came together or were brought together in an industrial critical mass, firstly seeking commercially viable products and then attempting to compete on an international scale alongside IBM and others. Its history charts a key period of the development of IT as a tool for automating government and commerce, in between the pioneering phase and IT as a ubiquitous, societal phenomenon.

Timeline of ICL

ICL was created in 1968 as a result of the Industrial Expansion Act and by this initiative, the Wilson Government’s Ministry of Technology, headed by Tony Benn, aimed to create a British computer industry that could compete with major world manufacturers such as IBM. It was formed through a merger of International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) (itself created by the merger of British Tabulating Machines & Powers-Samas), English Electric Leo Marconi (EELM) and Elliott Automation in 1968. The Government initially held a 10% stake and was a part-owner until 1980.

In the period since the end of World War II several companies attempted to establish computer manufacturing operations to exploit the UK’s advanced technological innovation but did not achieve the scale for long term commercial viability. In the late 1940’s Ferranti was developing machines based on university designs, including the ground breaking Atlas. Elliott Brothers / Automation were developing their 152 model for launch in 1950 and English Electric acquired the computer interests of the Marconi Company to enter the market. In the 1950’s LEO Computer was established, based on what is credited as the first commercial computer application, the Lyons Electronic Office, and International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) was formed by the merger of two other pioneering firms: in 1962 ICT delivered the its first transistor machine and the first to use core memory; the 1300 series. The 1960’s then saw a series of consolidations of the aforementioned players into two dominant firms; the English Electric Leo Marconi company and ICT, which came together in 1968 to form International Computers Limited.

In 1984 ICL was wholly acquired by STC (Standard Telephones and Cables) as a strategic step in the convergence of computers and telecommunications. In 1981, however, ICL had already formed an important link with the Japanese company Fujitsu. ICL needed a cheaper source of technology to develop new machines and negotiated access to Fujitsu’s Large Scale Integration (LSI) and packaging technologies. Initially the collaboration was presented as an arm’s length one, to avoid diluting ICL’s credentials as a European and British company but Fujitsu’s involvement with ICL at both the financial and the technical level steadily increased over the subsequent two decades. By 1998 Fujitsu was ICL’s sole shareholder and in 2002 the ICL brand was fully subsumed into Fujitsu Services

Products and performance

On its formation, the company inherited two main product lines: the ICT 1900 series of mainframe computers and, from English Electric, a range of IBM-compatible mainframe computers

When the companies were first merged the English Electric order books were full, while ICT (which had twice as many employees) was struggling, perhaps because the 1900 series was incompatible with the rest of the industry, with an architecture based on a 24 bit word and 6 bit character rather than the 8 bit byte that was becoming the industry norm. It was expected that the 1900 would be phased out in favour of the System 4, but the reverse was the case; possibly due to union and political pressure from the Wilson government. ICL initially thrived, but relied almost wholly on supplying the UK public sector with computers: significant customers included Post Office, the Inland Revenue, the Department for Work and Pensions, and the Ministry of Defence. The 1900’s were sold in several countries worldwide, but the largest slice of the market was always in the UK, One significant feature of the 1900 series was that programs would function unaltered on any 1900 system, i.e. without the need for recompilation. Unfortunately, ICT, and later ICL, was unable to capitalise on this major advantage to make significant inroads into IBM’s customer base.

Even before the merger that created ICL was complete, a working party had recommended that the new company should develop a new range of machines offering “acceptable compatibility with the current ranges of both companies”. This was also seen as a way to help achieve company unity for the newly formed organization. Its design drew on many sources, one being the Manchester University MU5.

In 1974 the 2900 series was finally launched. It was two years late but together with ICL’s small business systems made the remainder of the 1970s a very good period for ICL, achieving annual revenue growth of 20 per cent. The 2900 series ran the VME operating system (virtual machine environment) operating system, which contributed to the launch delay but was a world leader in its day

Series 39, launched in 1985 followed the same essential architecture as 2900 series, but was a dramatic step forward in hardware technology. Indeed technical innovation and excellence was a feature of ICL, evident in ground-breaking hardware such as; CAFS – Content Addressable Filestore, DAP – Distributed Array Processor and the Unix-based Advanced Graphic Workstations. Although not financial successes in their own right, they broadened the scope of IT and inspired others.

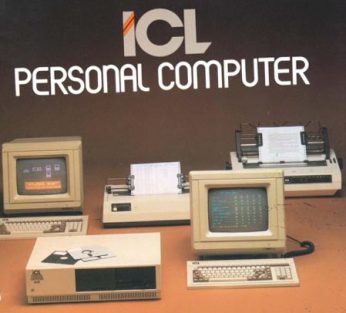

In later years, ICL attempted to diversify its product line but it hardware business profits always depended on the mainframe customer base. New ventures included marketing a range of powerful IBM clones made by Fujitsu, various minicomputer and personal computer ranges and (more successfully) a range of retail point-of-sale equipment and back-office software.

Services

While ICL was primarily known for its hardware design and manufacturing capabilities, its service capability was always an important component tin the business model. ICL Dataskil was a software house, that developed commercial programs and some utility software for the ICL marketplace. It also provided consultants and project teams to work on ICL’s or direct clients’ 1900 and 2900 projects. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s there was a recognition that ICL could not compete with the market size and volumes achieved by US competitors in the hardware business. Moving to services was the way forward. By 1991 this profitable area accounted for about the same amount of revenue as hardware–50% of turnover–and ICL could claim the number one position in Britain’s market for computer services.

International

The European industry was fragmented with each company relying heavily on its home market. It was acknowledged that a single large European company would be much better enabled to compete with the US companies. To this end talks took place between the group known as BISON (Bull, ICL, Siemens, Olivetti, Nixdorf) but national politics and NIH ensured no success.

One successful European collaboration was the ECRC, European Computer Research Centre Gmbh. Founded and equally owned by Bull, ICL and Siemens it undertook research with the results being freely available to all partners for them to turn into products. Based in Munich it produced many exciting ideas for a time under the chairmanship of Charles Hughes. At one point ICL was lining up to buy a significant French services company but that fell foul of other strategic initiatives.

Photo: Professional Images/@ProfImages

Government, policy and people

Not surprisingly as the UK’s flagship manufacturer in an area of new technology and a period of economic and industrial turbulence, ICL’s direction was shaped to a large degree by government policy and key personalities in the industry. The Wilson and Heath Governments were closely involved in ICL and the company’s fortunes depended on and influenced the careers of many names in the industry; some are mentioned below and others are included in the AIT leaders’ interviews, including Charles Hughes (mentioned above and Sir Peter Gershon – both graduate trainees who went on to serve on various boards during their time there). Both Bill Ellis and Ninian Eadie, who form part of the archive also spent much of their careers at ICL.

The Ministry of Technology stimulated the creation of ICL but almost as soon as the development of the new range of computers had started, there was a recession in the computer market. In the wake of damaging press commentary on ICL’s management, the company fired its chairman, Sir John Wall, and managing director Arthur Humphreys (a pivotal figure in large part responsible for the success of the 1900). Tom Hudson, formerly managing director of IBM (U.K.), and Geoff Cross of Sperry Rand were appointed to the positions. During the next five years, Cross transformed the company and secured from the government a modest extra ‘launching aid’ grant of £14.2 million toward the new range system. The government later provided £25.8 million in launching aid, and ICL introduced its new range in October 1974.

In 1981 trying to develop new, lower end machines in the 2900 range ICL ran into a financial crisis, leading to a takeover bid from Unisys. Despite outstanding financial results in 1979, ICL found itself in trouble following the introduction of the IBM 4300 and the unfavourable turn in exchange rates. By the end of 1981 ICL had racked up a loss of £18.7 million for the year.

The British Government stepped in with a loan guarantee for ICL, enabling the company to stay independent, and introduced Sir Christopher Laidlaw as chairman and Robb Wilmot, formerly of Texas Instruments, as managing director. Wilmot, aged just 36, cancelled the in-house development of large-scale integrated circuit (LSI) technology and, instead, negotiated the seminal agreement for Fujitsu’s LSI and packaging technologies. Combined with ICL’s in-house CAD capability, this enabled ICL to design and manufacture the Series 39 level 30 and 80 computers.

1982 Christopher Laidlaw, was knighted for his efforts in the company revival and retired in 1984. Later that year Standard Telephones and Cables (STC) took over ICL. The rationale for this was the expected convergence of computers and telecommunications. Peter Bonfield, who joined ICL at the same time as Robb Wilmot, also from Texas Instruments, succeeded Wilmot as managing director. Wilmot served as chairman for one year.

The merger was soon followed by a financial crisis at STC, leading to Arthur Walsh becoming chief executive of STC and Bonfield being appointed as chairman and managing director of ICL. Within a few years ICL was contributing 60% of the profits and turnover of the combined group. By the early 1990s ICL reportedly had one of the highest returns on capital of any company in the information technology industry.

In the late 1990’s it was widely expected that Fujitsu would float ICL. When Peter Bonfield left ICL in 1995 to become chief executive of BT, Keith Todd stepped up to take the top job and from 1998 he was promising that ICL would be floated on the stock exchange by the end of 2000.

The company repositioned from manufacturer to service provider but in the aftermath of Y2K was loss making and hi-tech valuations had plummeted, leading Fujitsu to shelve the plan, in turn prompting the resignation of Keith Todd.

Within two years the brand of ICL had disappeared.

Items drawn on to write the article include:

The Early Computer Industry: Limitations of Scale and Scope A. Gandy 30 November 2012 Springer

The Independent Article – ICL Chief Ousted

Telegraph Article – The End of an Era – ICL becomes Fujitsu

funding universe – company histories – ICL plc

New Scientist Article – Google Books

Wikipedia – International Computers Limited

Campbell-Kelly, Martin, ICL: A Business and Technical History, Oxford University Press, 1989

Further information

- We group our interviews by company. You can find more interviews with people who worked at ICL by clicking here

- The University of Manchester Library has an archive fonds for ICL, view their catalogue on the Archives Hub here

- The Science Museum has a collection of manuals, technical drawings and software material from ICL, indexed by the Computer Conservation Society. View their catalogue here