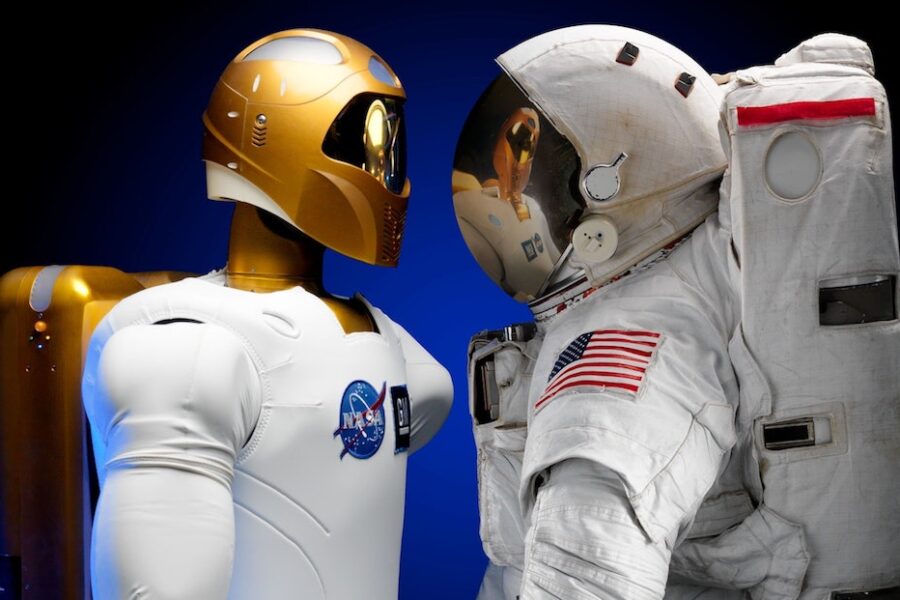

Main Image: Could we see a future where AI and human intelligence complement each other in space exploration? Words by Adrian Murphy

Against a backdrop of growing concern (and excitement) our industry theme for May 2023, is Artificial Intelligence (AI) and we have been exploring our archives to find out what interviewees have had to say about the technology from their careers and experience from 1960s to the present day.

AI is disrupting almost every industry and is making astonishing advancements in manufacturing, administration and healthcare as well as enabling a networked society. Last week Goldman Sachs said 300 million jobs (18%) worldwide could be computerised through technologies such as ChatGPT.

Some also point to the fact that we are now at the point where, unchecked, AI will increase its capabilities and become artificial general intelligence with machines having cognitive capabilities and potentially being able to improve itself and surpass human abilities.

To get a balanced view, we’ve featured eight individuals interviewed between 2019 to 2023 that range from data analysts to scientists who have researched, written about, taught, developed and used the technology in their day-to-day professions.

Generative AI and ChatGPT

The recent launch of ChatGPT, (Chatbot Generative Pre-trained Transformer) and other chatbots such as Google’s Bard, Meta’s LLaMA and Snapchat’s My AI, have been causing a stir around the world as their capabilities could lead to disinformation as well as huge job losses.

This is because of ChatGPT-4’s capabilities to not only process text but its ability to comment and analyse graphics and images, for example, creating websites from hand-drawn sketches.

Government regulation and the open letter

Politicians around the world, especially in the US, are calling for answers on potential threats the technology poses and whether it should be regulated by the government.

Last week the chief executive of OpenAI – the developer of ChatGPT – Sam Altman, faced questions about AI at a hearing in the US Senate where he urged Congress to impose rules on Big Tech. AI was also on the agenda of the G7 summit in Japan at the weekend.

All this follows an open letter published at the end of March by Future of Life Institute warning of the dangers posed by recent advances and called for a pause in generative AI systems more powerful than GPT-4. The 1,800 signatories included Elon Musk and Steve Wosniak.

The letter called for a six-month pause on developing large-scale AI projects asked pertinent questions such as: “Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us? Should we risk loss of control over civilization?”

Dr Andrew Rogoyski – we need to treat generative AI very seriously

At the end of March 2023 AIT interviewed Dr Andrew Rogoyski, Director of Innovation and Partnerships at the Surrey Institute for People-Centred AI, who tried to sign the letter but ironically the system crashed and he was unable to do so.

“It said we need to have a cold, hard look at what we are about to do because we are getting closer to the point where some breakthrough may occur. Some argue we are getting close to artificial general intelligence, we are getting to the point of singularity where AI start to design themselves and run away, we are getting closer to the idea that we may not be able to control an AI that we develop.

“There’s a lot of debate about the pros and cons and the realities of those points but I do think we need to treat those topics very, very seriously.”

For example, he says: “The large language models are starting to show … that they are understanding the structure of human communication in a way that we haven’t yet realised how to do … and people are already talking about what’s going to be put into GPT-5, hence the letter.”

How did we get here?

In some ways AI can be traced back to the British mathematician and computer scientist, Alan Turing and his use of machines to break the Enigma code during the Second World War.

In 1950 he posed the question ‘Can machines think?’ in his seminal paper: Computer Machinery and Intelligence – introducing the Turing Test of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behaviour equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human.

By 1961, the world was introduced to the first industrial robot, the Unimate, used by General Motors – this and subsequent robotics led to job losses in the automotive and other industries worldwide. Just five years later MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum released the first chatbot, Eliza, that allowed limited conversations between humans and machines.

Then, both in the UK and the US, came what was to be described as an AI winter where government funding was cut.

Despite this in 1995 Richard Wallace, inspired by Eliza, began work on A.L.I.C.E. (Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity), a natural language processing chatterbot, which although impressive, still did not pass the Turing Test.

By the early 2010s deep learning methods had progressed to the point of Siri being introduced to smart phones in 2011 and Alexa to smart speakers in 2014 a pre-curser to the AI spring that we are experiencing today.

The Lighthill Report

In the UK the AI winter began with the Lighthill Report, published in Artificial Intelligence: a paper symposium 1973, by James Lighthill for the British Science Research Council. It noted the lack of impact from research in robotics and language processing at the time and led to a subsequent decision by the UK government to end support for AI research in most British universities.

This had consequences for Professor Alan Bundy CBE who was interviewed by AIT in June 2020. He joined the University of Edinburgh’s Meta-Mathematics Unit as a Research Assistant in 1971. He worked in Bernard Meltzer’s Department of Artificial Intelligence which included Bob Kowalski, Pat Hayes, Bob Boyer and J Moore, all of whom have gone on to make major contributions to artificial intelligence and theorem proving.

During his time at Edinburgh Alan has seen the department grow and shrink depending on the appetite for AI, including a reduction in the size of the department following the Lighthill report.

He says: “One thing that drives [this shift] is over-expectation. In the very earliest days, people such as Newell and Simon came up with this famous list of goals which they thought were going to be solved in ten years and it was far too ambitious.”

Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon contributed to the Information Processing Language (1956) and two of the earliest AI programs, the Logic Theory Machine (1956) and the General Problem Solver (1957).

The Logic Theory program was presented at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence in 1956, in New Hampshire, now widely considered the to be the founding of artificial intelligence as a field.

“Interestingly, some of [the problems] have been solved more recently, an order of magnitude longer than they anticipated,” says Alan.

He believes that what will make a difference this time if the passion for AI drops off is that the science community has industrial successes to point to.

“There have been applications of machine learning which have been transformative in medicine, in self-driving cars, in image recognition, speech recognition and so on. We now have those successes we can point to, so I don’t think there’s a danger that suddenly all the funding will be removed because people will still want to fund those successes, but there will be a period of disillusion when people realise the limitations of these systems and how easily they can be fooled.”

The fourth industrial revolution and the emergence of an AI sector in the UK

In 2017 Dame Wendy Hall CBE, a British Computer Scientist, Regius Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southampton and Executive of the Web Science Institute, was asked to co-chair a UK government review on Artificial Intelligence with Jérôme Pesenti. Dame Wendy was interviewed by AIT in November 2018 just seven months after the government announced £1bn Sector deal as a result of her report.

She believes the AI review was catalysed by Klaus Schwab’s book, The Fourth Industrial Revolution (the title he attributes to the current speed of change with AI), which he’d given to political leaders at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2016 when the book was publication.

“They all came back thinking, ‘gosh, we’ve got to do something about this AI revolution otherwise we are going to end up losing all the jobs, and all the new jobs are going to be created in America and China, so that was part of the spark.

“The concept of an AI sector perfectly complemented the work that the Alan Turing Institute was doing to stimulate the design and development of the algorithms that would make use of big data and enable AI.

“The next five years will only be the start of AI [which is where we are at now] and it won’t be mainstream for two to three decades.

“People must learn to manage the balance between digital devices and real life, and the big issues relate to how technology and society work together.”

“In the longer term, AI presents enormous opportunities to deal with mundane jobs, but social contracts have to be renegotiated and jobs that need people must be adequately valued. While we don’t know exactly how AI will develop, we can’t ignore it and we can’t pretend it won’t happen.”

Modern Magic or Dangerous Future?

Yorick Wilks, who died recently, was involved with AI since the 1960s and published a book in 2019 entitled ‘Artificial Intelligence: Modern Magic or Dangerous Future?’ He worked for long periods in the US and in 1985 became the director of a state-funded artificial intelligence laboratory and helped found a new technology called information extraction.

In his interview with AIT in September 2019, Wilks said: “I think the educated public, and even the uneducated public, are quite suspicious of AI now … they’re double-minded.

“They see the benefits; they can’t imagine living without intelligent phones. People are aware that there are dangers and there are positives; this is always true of science. Lots of science is both frightening and enormously beneficial and AI is just like that. As always with these things, science, AI, engineering, have given us the tools that are dangerous, but it will also, I believe, I’m an optimist, give us the tools to correct it.

“So however dangerous we think Facebook and political advertising are, it will also give us the tools to correct it.”

Yorick said the biggest challenge for AI is deep learning. “The best people in deep learning can already see what the limitations are. They know that much of the success of deep learning is because of very careful choice of what are called priors. They choose very carefully which features to probe the data with.

“One thing we know is that human beings do not learn in the way deep learning systems do. Human beings learn intuitively and immediately … deep learning has had some great advances, but it’s narrow and it’s fragile. We’re still going to have to go back at some stage to other methods that try to mimic how it is we do things.”

Human intelligence and AI working together

In the early 2000s, Dr Angus Cheong saw the potential of data analysis and in his interview with AIT conducted in November 2022 he talks about how Human Intelligence (HI) and AI can work together to interpret peoples’ comments on social media, known in data analytics as ‘unstructured data’, to improve the results of offline human-produced surveys.

“I think AI is very important. It will be crucial to everything; but AI alone is not sufficient. The integration of AI and HI is more practical and sensible for us to move forward to make meaningful things happen. Especially in our field, when you try to understand people’s behaviour, people’s attitudes, if you rely solely on AI there could be some issues, for example, the accuracy of the meaning, the interpretation of what the data tell you.

“AI would help us to enhance the efficiency and from complexity to simplicity, but still in the end, we need people’s intelligence to interpret and to make decisions. In the area of natural language processing, if you want to understand people’s mind, you’ve got to combine artificial intelligence and human intelligence.”

However, Angus said there are quite a number of issues that we need to pay attention to, such as disinformation and fake accounts, which are taking place in the social media era.

Will expectations meet achievements?

Professor Nick Jennings, Vice-Provost for Research and Professor of Artificial Intelligence at Imperial College London, who was interviewed by AIT in March 2020, said that AI was also going through an amazing time of interest, however, he was sceptical about the expectations meeting the achievements.

“I’m worried that we’re going slightly over the top in terms of what AI can do for society. My fear is that we’re going to go down towards the trough of disillusionment in terms of it as a field and that people we will not be able to deliver everything that being promised at the moment in the time-frames that we think we will. I see lots of naivety around AI … I think the challenge is around managing expectations, about getting people to understand what AI is, and what it can do, and what it is not and what it can’t do.

“Much greater realism on AI is really important that we get right. It’s a powerful computing technology, but that’s what it is; it is not magic.

“Having said all of that, I think, we really will see a number of transformative applications appearing in the coming ten years and we’ll see great applications of AI in healthcare, energy, climate change and education.”

AI creativity and emotions

As the power of technology continues to grow at an exponential rate, the question of whether humans will ever be replaced is still unlikely according to Professor Denis Noble emeritus and co-director of Computational Physiology at the University of Oxford.

He was interviewed by AIT in September 2021 and said: “That may puzzle people because surely it must be the case that if computing power continues to increase in the way that it is and resources increase then not only will AI beat us at chess, and various other contexts, processes of algorithms of one kind or another, will surely end up even replacing us, there will be the virtual human, not just as a computational model, but it would actually be acting like us.”

Professor Noble has written a story about the creation of a female AI who goes in search of a boyfriend but struggles to actually understand creativity in life. Denis says that this is due to the fact that computers are made of fixed components.

“The computer I used in 1960, your desktop today, or even the most powerful computer in the world is made of fixed components. The microchip material, whether it is semi-conductor or metal, is a fixed solid structure. Cells in the body are not like that, there is stochasticity occurring the whole time and we use that stochasticity to be creative.”

But can it do things that we never could?

Danielle George, Professor of Radio Frequency and Associate Vice President at the University of Manchester, who was interviewed by AIT in July 2021, believes that the potential of AI and HI to combine in the future is a fascinating area which may see us evolve, especially in relation to space travel.

“AI is already radically changing our everyday lives. It impacts the future of pretty much every industry and every human being on the planet and it will continue to act as a technological innovator for the foreseeable future.”

She explains: “As humans, we are not biologically set up to travel in space. There is an awful lot of technology that has to go behind us to be able to travel in space. Could we get to a point where we evolve and there’s this morphing of humans and Artificial Intelligence, and it’s that that then does the space exploration and it is that that colonises other planets if that is what we want to do, or explores other planets around the universe, not just in our solar system. I think it’s a fascinating area.

“In the past, we’ve kept ethics and politics and technology separate and they’re coming together a bit more now, which is a good thing. Just because we can do something from a technology point of view, we do need to question is it the right thing ethically, morally, politically, financially, etc. I think getting the younger generation to think about all of those on the whole is a fascinating time for them.”

Where next?

AI is here to stay, and the latest developments are indeed a potential gamechanger to how our industry and lives will operate in the future and that will need scrutiny and regulation as Dr Andrew Rogoyski said and will cause some pushback.

However, it is worth noting Dame Wendy Hall’s comments that it could be two or three decades before the latest technology becomes mainstream, partly because it is still being developed and assessed and partly because so much will have been invested in current systems that it will take a number of years for organisations to see the financial benefits of AI.

And as she mentions social contracts will have to be developed and training people to adapt to the changes and new technologies will be important.

There is a common thread throughout many of the above experts’ comments: that Human Intelligence and Artificial intelligence need to work together and that the ethics of these far-reaching developments need to be taken on by the technologists and the politicians.

In March 2023 the UK government heeded the calls to do just that and published a white paper, AI regulation: a pro-innovation approach, and is now seeking views through a consultation.

It seems that the fourth industrial revolution is really here.